“We envision a future where society values care. To get there, society has to see care.” Working Assumptions

Introduction

There is a saying that a “photograph is worth a thousand words,” but what one reader of a photograph says about the image can be quite different from what another reader might say. Two people looking at the same picture can come to two different conclusions about its meaning. But understanding a photograph is not just dependent on what the viewer sees, it depends on what the viewer sees in combination with trying to understand what the photographer is trying to communicate. It is important to know that a photographer makes decisions, like artists or writers, about what to include in a photograph’s composition, and what not to include, and which photos to show the public, depending on what idea or message he or she wants to communicate.

This is especially true when viewing photographs produced with the goal of documenting specific events. The decision to publish, to make public, a specific image is dependent on what message or narrative the publisher or photographer wants to communicate. In this context it is helpful to know how the goal of the photographer, or the photographic assignment, guides the selection of a subject. This knowledge of purpose aids in our understanding of the photo, its meaning, and maybe its importance.

But the photographer or the publisher are not the only ones with a stake in what an image contains and communicates. We also want to consider how the subject of the photo might want, or not want to be, seen. When we are the subject of a photo, how do we want people to see us? What about our lives and our lived experiences do we want and not want communicated?

Two Photographs from the Great Depression Era

A good example of these ideas and questions can be seen by a close look at two photographs taken by the photographer Walker Evans. Evans was part of a group of photographers hired by the federal government’s Farm Service Administration (FSA), between 1935 and 1943, to document American life during this time period. For photographers working for the FSA the photographic assignment was to add actual faces to the statistics about the economic problems faced by Americans living in rural areas during the Great Depression. The photos were to document the powerful impact of the Great Depression on people’s lives. The hope was that the images would engender other Americans to care about the plight of people, fellow citizens, grappling with the impact of the Great Depression and years of poverty in their lives. And then use that care to gather support for New Deal farm aid programs drafted with a goal of improving those very same lives.

In the summer of 1936, while on leave from the FSA, Evans was sent by Fortune Magazine, with writer James Agee, to Hale County Alabama to document the lives of three families of sharecroppers. What Evans and Agee documented was later published in the book

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941). The photographs Agee and Evans included in the book told a story of poverty and hardship, their goal in writing the book. The historian Lawrence Levine tells the story of two photos taken by Evans for that assignment, one that was included in the book and one that was left out.

Levine writes,

In their account of three sharecropper families, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) James Agee and Walker Evans included many photos of the Burroughs family, including their widely reproduced shot of an unshaven, tired, anxious Floyd Burroughs in a tattered work shirt [see photo #1 below]. They chose not to use a picture that Floyd Burroughs requested they take of him, his arms thrown confidently around the shoulders of his smiling wife and sister-in-law, with his children posed in front, everyone looking clean and contented in their best clothing [see photo #2 below]. It was a classic family pose but not one congenial to the purposes of the book from which it was excluded…The fact that Burroughs, who seems to have no objections to the other photographs that were taken, wanted himself and his family pictured in this light as well, is an important part of the thirties that we can ignore only at great cost to our understanding of the self-images and aspirations of people like the Burroughs. (Levine, Historian and the Icon, p. 21-22.)

Photo #1

Photo #1 – Floyd Burroughs Source: Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, 1936, Walker Evans photographer.

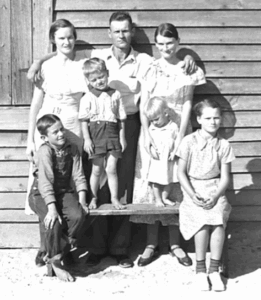

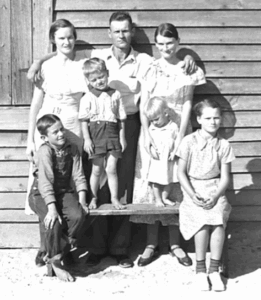

Photo #2

Photo #2 – Floyd Burroughs and Family Source: Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, 1936, Walker Evans photographer.

As Levine writes, Burroughs did not have any objections to photo #1, but wanted his family also pictured in a positive light as well (photo #2). He was willing to go along with the portrayal of his hard times, but also said there was more to his story.

Viewing these photos in the historical context – The Great Depression

As mentioned, a major purpose of the FSA was to gather support for New Deal programs that helped people get back on their feet who had been thrown out of work and were facing a lack of housing and food as a result of the Great Depression. But not all Americans agreed that federal government programs were the best solution to that problem. The debate around the best approach was at the center of the 1932 presidential election. Then President Hoover believed that problems of poverty and unemployment were best left to “voluntary organization and community service.” He feared that direct federal relief programs [providing money and/or jobs directly to individuals] would undermine individual character by making recipients dependent on the government.1 Hoover, though, was defeated for the presidency by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In his campaign for president Roosevelt put forth a different view of the role of government in solving these economic problems. He said, “What do the people of America want more than anything else? To my mind, they want two things: work, with all the moral and spiritual values that go with it; and with work, a reasonable measure of [economic] security–security for themselves and for their wives and children…I say that while primary responsibility for relief rests with localities now, as ever, yet the Federal Government has always had and still has a continuing responsibility for the broader public welfare…”2 More directly, Roosevelt argued, “…An American Government cannot permit Americans to starve.”3

Understanding the Great Depression

To help us better understand how the Great Depression might have impacted Americans on a more personal level, view this short video from the historian David Kennedy.

What does David Kennedy’s story about how the Great Depression impacted his father’s self-image add to our understanding of how Floyd Burroughs might have viewed his economic situation?

David Kennedy tells his story with the aid of historic photographs; what aspects of the story do the photographs help highlight and why do you think he wanted them included here?

Connecting to the historical context and questions of care and community

Stories and photos of family and work, both in the past and present, capture important moments in people’s lives and give us the opportunity to see beyond our own work and family contexts. They give us the chance to understand and empathize with others, seeing both commonalities and differences. And in doing so raise questions about the choices we make about who we care for and how. How far should our “circles of care” extend beyond our immediate family? To our next-door neighbor? To the homeless person we see on the street? To the person living in the next town? To a family living in another state? Another nation? And how, as we consider how far we extend our care, does this care get manifested? Are acts of care only personal actions, or are acts of care something for a community, state, or nation to take on together?

These questions of who we care for, and how, were central to the 1930s debate over the role of government in addressing the economic challenges of the Great Depression, and are still central to our public conversation and policies around such issues as health care, child care, minimum wage, the environment, and homelessness.

Circles of Care

With these questions in mind let’s re-look at the two Burroughs and photos and consider what Levine’s story, and its historical context, reveals about the “circles of care” questions raised above.

- Why do you think Burroughs wanted his family photo (#2) taken? What did he want people to see about him and his family through that image?

- Why do you think Burroughs didn’t object to the other photo taken (#1)? What else might he have wanted people to know about his life?

Given your responses to the above two questions, speculate on what Burroughs might have thought about the 1930s debate around the role of government in helping people.

- Would Hoover’s argument have appealed to him? Explain why or why not.

- Would Roosevelt’s argument have appealed to him? Explain why or why not.

In considering the role of the FSA Levine concludes,

“The photographers may have set about documenting the immediate impact of the severe economic depression, but they succeeded in creating a remarkable portrait of their countrymen’s resiliency and culture…In these photographs…we are made witness to a complex blend of despair and faith, dependency and self-sufficiency, degradation and dignity, suffering and joy.” (Levine, P. 27)

Is Levine’s argument supported by the two Burroughs photos? Explain your response.

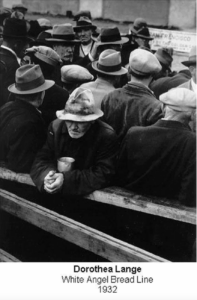

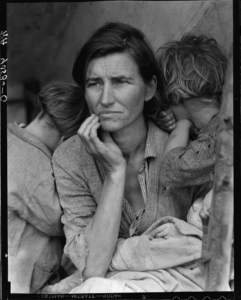

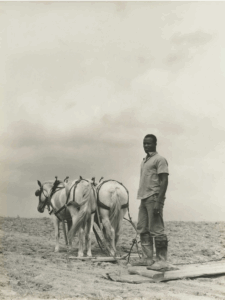

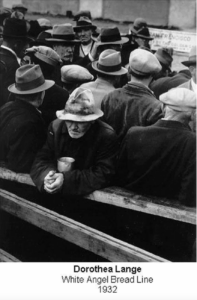

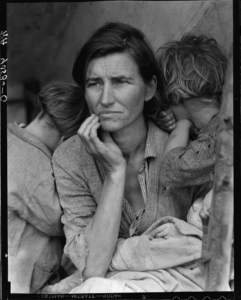

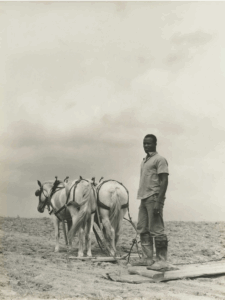

Farm Service Administration Photos and Reflection

Examine the following sampling of other famous FSA photos and use what you see to support or revise your response to question #4.

“Migrant Mother” – Dorothea Lange, 1936

Along the highway near Bakersfield, California. Dust bowl refugees – Dorothea Lange, photographer, 1935

Tenant farmer, Lee County, Mississippi, Arthur Rothstein photographer, 1935.

Dust Storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma, Arthur Rothstein, photographer, 1936.

Unemployed coal miner’s daughter carrying home a can of kerosene. Marion Post Wolcott, photographer, Scotts Run, W. Va., 1938

Greene County, Georgia, Jack Delano photographer, 1941.

Making Connections

Connections to your own photo assignment – how might what was learned from this lesson connect your own photo assignment. Who are the subjects? What are their goals and what are yours? What do you want to make public and what do you not want to make public? Etc.

Photo essays tell a story with photos and words. In a social documentary photo essay, the photographer/writer aims to draw the public’s attention to an ongoing social issue, often with an appeal to civic action. And social documentary photo essays can also tell very personal stories about the lives people lead and the issues and challenges they face. From Lewis Hine’s photos of child labor in the early 1900s, to Gordon Parks, “American Gothic,” portrait of Ella Parks in 1942, to John Phillip Jones photos of the Vietnam War, photographers and their documenting of social issues have prompted public calls for civic action to take on the issues made visible through the images.

In the American Creed series, young leaders are telling their stories and bringing attention to issues they care about in their communities through photo essays. These are examples of civically engaged writing and illustrate how young adults might engage audiences in the issues, questions, and possible social actions that matter to them, their families, and their communities. They can be used as mentor texts to support students in doing their own civically engaged writing.

Below are two of these photo essays from the American Creed project – “Salmon Tales – Subsistence on the Kenai Peninsula” by Sam Schimmel and “Slag Valley” by Trinity Colon. Using the National Writing Project’s Civically Engaged Analysis Continuum (CEWAC), I have highlighted the composition choices of both authors and featured aspects of their photo essays that make them strong pieces of civically engaged writing.

NWP’s Civically Engaged Analysis Continuum

The Civically Engaged Writing Analysis Continuum (CEWAC) developed by the National Writing Project is designed to assess a student’s ability to engage in public arguments rooted in evidence and reasoning and to enter productive civic conversations. Through that process, CEWAC helps both teachers and students identify what makes for strong civic writing.

CEWAC looks at four key components in a composition:

- Employs a public voice – Analyzes how the writing employs rhetorical strategies, tone and style to contribute to civic discourse or influence action, and how it establishes a writer’s credibility. Public voice is directed beyond one’s immediate family or friends.

- Argues a position based on reasoning and evidence – Analyzes how the writing uses reasoning, interprets and presents evidence, and, when appropriate for purpose and audience, addresses alternate positions or perspectives. Evidence may include personal experience as well as primary and secondary research.

- Advocates civic engagement or action – Analyzes how the writing, as crafted for an intended audience, raises awareness and establishes the public importance of a civic issue. When appropriate, advocates for a desired change or civic action, explaining why the action is reasonable and feasible.

- Employs a structure to support a position – Analyzes how organization and structure help develop the central argument, including openings, closings, and linkages.

Learn more at cewac.nwp.org

Analysis of American Creed photo essays using CEWAC

As students and youth take on the task of creating their own civically engaged compositions, it is important to consider what makes a strong photo essay as well as what qualities would make a photo essay a strong piece of civically engaged writing.

Below are two examples:

- Annotation of “Salmon Tales – Subsistence on the Kenai Peninsula”

- Annotation of “Slag Valley”

Related worksheet: What Makes an American Creed Photo Essay a Strong Piece of Civically Engaged Writing

Annotation of “Salmon Tales – Subsistence on the Kenai Peninsula”

The photographer and writer Sam Schimmel is a member of the Kenaitze Indian Tribe in Alaska where he hopes to help his people negotiate a healthier, more sustainable economy that aligns with his community’s values and the need to protect the environment.

See: Sam Schimmel’s “Salmon Tales” | American Creed

The annotations here are my notes about the ways that Sam Schimmel’s photo essay is a strong piece of civically engaged writing. These notes can be discussed with students directly or you can invite the group’s own annotation first and then use my version for discussion.

Employs a Public Voice

To support his goal of raising awareness of the challenges facing his people, Schimmel effectively engages the audience through a series of family photos and captions that help tell two important stories.

- First, the story of how his family works together to continue using traditional fishing methods. One photo caption reads, “Although we use different materials to make nets than our ancestors did, it still requires the same know-how. Here, Allie is hanging a lead line. This heavy rope is attached so the net sinks. You need to place the lead line at the right intervals between the mesh so it sits in the water properly.”

- Secondly, the story of how the skills of subsistence fishing are passed down from generation to generation. A photo caption reads, “My aunt MaryAnn points to the direction of the fish scales as she explains that we need to tie the twine on the tail end of the strip or else the salmon will slip out when it is hung to dry.”

Taken all together the images and their captions support and drive forward an inspiring family story of skill and resilience that should engage and resonate with most readers.

The choice of photos, along with the captions, also firmly establishes the writer’s credibility. He demonstrates deep knowledge about the work of subsistence fishing. One caption reads, “My cousin Julianne collects driftwood from the beach. The ocean purges the cottonwood of its tannins. This makes the driftwood perfect for smoking salmon without transmitting the bitter taste of tannins to the fish.” This is a person who is also knowledgeable about the issues and history confronting his people as they seek to maintain this way of life. Someone whose story we need to know if we are to understand the impact of many current public policies affecting his tribes’ right to their keep at their traditional livelihood. Another caption reads, “Both of my aunties sit on our Tribal council. They work hard to ensure the well-being of the community, from fighting for our rights to maintaining Tribal programs that ensure the continuity of our traditional subsistence practices. They also participate in subsistence activities, like fishing and preparing salmon.”

Through his choice of images and text the author has clearly demonstrated a command of the issue and built a connection with the reader that elicits empathy and an awareness of what it might take for the family and tribe to continue their traditional fishing story.

Argues a Position Based on Reasoning and Evidence

The author writes, “[My aunt] MaryAnn reminds me that ‘because we’ve been fisherpeople from time immemorial, we are the caretakers of these waters –our responsibility as well as our right.’”

Through the thoughtful selection of images, the author supports this position by illustrating what it might mean to be caretakers of the waters. Two images help address the responsibility claim.

First, about the use of available resources, in this case driftwood, to help process the fish that feed the family.

And, secondly, about knowing the proper way to prepare the food that will help feed the family.

In addition, the author makes effective use of history and law to support the position that fishing in the waters at their traditional home is a right they are actively trying to protect. The author tells us the story of his aunt’s confrontation with state authorities around that right, “She set a net in the mouth of the Cook Inlet to fish without a commercial permit where we’ve been subsistence fishing for thousands of years. The state government threatened her with jail time and a $150,000 fine. She pushed for a hearing because she knew she could win…Under international law, she knew that ‘in no case may a people be deprived of their means of subsistence.’”

Advocates Civic Engagement or Action

In many cases a piece of public writing is civic engagement and action. That is the case with this photo essay.

Through the narrative the reader is made aware of the importance of subsistence fishing to the Indigenous community to which the author belongs, and the threats to that economy in both the present and future. In terms of the present he writes, citing the impact of climate change, “Weather patterns change unpredictably, and we can’t rely as much on those thousands of years of accrued knowledge that allowed us to read the ocean and the woods. Three years ago, I flew in a plane across the Cook Inlet. I looked down on the water and there were thousands of dead fish floating because the water was too warm. That year we had terrible fires and heat waves that lasted weeks and killed off fish. So this year, we’re going to have a smaller fish return. Some years we cannot harvest enough fish to feed our community.” With an eye on the future of his community, he continues to raise awareness by writing, “Consequently, the number of kids who are brought up taught to fish for subsistence decreases. This has a downstream impact where fewer kids have a sense of identity, or are involved with their community.”

Besides itself being a piece of civic action, the author includes an account of civic actions taken by his aunt in the fight for the community’s right to continue their subsistence fishing. Her actions, starting with an act of civil disobedience resulted in a legal victory that won the tribe the right to continue subsistence fishing. He writes, “Under international law, she [Aunt MaryAnn} knew that in no case may a people deprived of their means of subsistence.’ She won her case and we won the right to our Tribal nets.”

Through this account the writer makes clear that these are actions he admires and advocates for as part of the entire effort to protect the community’s right to subsistence fishing.

Employs a Structure

In this photo essay, images and words are placed in a specific to develop a narrative that develops for the reader an awareness of a civic issue facing the author’s community.

This essay first starts by introducing the reader, through both words and images, to the historical and social context at the center of this account.

For example, in the essay’s third paragraph he writes, “Fishing has always been essential to the spiritual and physical health of our Indigenous community. Our Tribal fishery offers a resource to my generation and the next…” This focus on the resource for generations is thoughtfully supported by this image and caption which immediately follow that paragraph.

“My cousin Julianne pulls out the gill net with some fresh salmon that will be brought back to the Tribal fishery to be cleaned.

When I was 6 or 7, I remember fishing with a cousin for 12 hours on the east side of the Cook Inlet.”

These words and images are followed by a series of images and words that bring to life the story of the community’s continued struggle to protect their subsistence rights. The essay concludes with an image and words that help the reader understand how important the civic actions taken by her Aunt MaryAnn were to the community as whole.

“My auntie MaryAnn has been advocating for decades for our tribe’s fishing and subsistence rights. In her work, she has met many other Indigenous leaders and advocates and has been given gifts like this bag in honor of her work and friendship. In the background, my uncle Bill.”

Annotation of “Slag Valley”

Trinity Colón works towards better health and quality of life in her industrial Southeast Chicago neighborhood, known as “Slag Valley.” In this photography project, she reflects on the beauty and character of her community, and her pursuit of education in order to imagine and create new opportunities for herself and others.

See: Trinity Colón’s “Slag Valley” | American Creed

The annotations here are my notes about the ways that Trinity Colón’s photo essay is a strong piece of civically engaged writing. These notes can be discussed with students directly or you can invite the group’s own annotation first and then use my version for discussion.

Employs a Public Voice

To support her goal of raising awareness of the challenges facing people in her neighborhood the author effectively engages the audience through a series of photos and captions that help tell two important stories.

First, the story of how industrial pollution impacts her and the people of her community. One photo depicts a basketball court covered with weeds and located right next to a train track.

It was paired with a caption that reads, “Growing up, it felt hard to be proud of where I was from because the city of Chicago wasn’t caring for my community. I grew up with pollution in my backyard. When you see and smell smoke stacks and dirty industry each time you take the garbage out or walk around, it’s hard to feel that sense of pride. “

Another photo caption reads, “Pollution is constant. It’s every day. Regardless of the measures that you take, regardless if you wear a mask, it’s in our soil, our air, our homes, our bodies.”

But the story of industrial pollution is not the only story being told in this photo essay. She also relates her own story. A story of personal growth as she learns to find beauty in the strength of the people in her community and in the other parts of her neighborhood’s landscape. One caption reads, “I’m learning compassion. I believe in the everyday people working in industry and operating industrial facilities. I’ve learned that we all have a very shared love for the community that we live in, and for the families that live here.”

This is a young woman who thoughtfully illustrates and articulates the issues confronting the people in her neighborhood, but she also demonstrates a reflective knowledge of how she herself might continue to be part of this community, and what it might take to be an agent of change. She writes “I’m in a transition from living on the southeast side of Chicago to being in college at Northwestern University, north of Chicago, in Evanston. I’m still near home, so I’m always trying to stay connected in both worlds. I’m very grateful for the people who have allowed me to grow as a person, as an organizer, and as a student.”

If one of her main audiences for this photo essay is the members of her community, the author, through her images and words, establishes her credibility. She demonstrates a command of the shared issue they face and why she is one voice in the community to be listened to and valued. For audiences beyond her community, she establishes a credible voice that is simultaneously open, inquiring, passionate and considered. Someone whose story we need to hear if we are to begin to understand the varied impact of American industry on different communities across the nation. Her tone is direct, urgent, and personal, connecting strong images to personal reflection and community understanding.

Argues a Position Based on Reasoning and Evidence

Colon’s photo essay makes a strong and forceful argument about what it means for her community to live with and amid environmental pollution. Her well-chosen words and images articulate her position. Below is one photo and caption that helps build this argument.

“Pollution is constant. It’s every day. Regardless of the measures that you take, regardless if you wear a mask, it’s in our soil, our air, our homes, our bodies.”

The essay’s causal reasoning connects the historical presence of industrial “slag”, ongoing contamination, and the daily lives of her historically marginalized community. The narrative links visual evidence to the argumentative claim that this environmental history continues to shape the area and its people.

Colon’s own voice and the perspectives of her family/community serve as evidence rooted in lived experience, an important source of evidence in civically engaged writing.

She refers to the community’s industrial past, citing and elaborating on known facts about waste material left behind.

“The southeast side is a sacrifice zone for the city of Chicago. The city and state see it as a dumping ground, and that’s why industrial polluters feel so comfortable coming here. They have built over 70 industrial facilities within the neighborhood. The people that own and maintain these industrial facilities typically don’t live here. They don’t send their kids to play at local parks. They don’t shop and eat here like locals do.”

“Slag Valley” provides a reasonable, evidence-based narrative, weaving together images and words that make visible the personal and community experiences that build and support her argument.

Advocates Civic Engagement and/or Action

Through her photo essay Colón documents the impacts of industrial pollution on Southeast Chicago, but she also encourages her audience—especially youth, neighbors, and the broader public—to recognize environmental injustice and become part of the solution.

She invites members of her community to engage with her and each other, to see themselves as the agents of change needed to help the community unite, advocate, and heal. This is illustrated through the following image and text.

”I’m learning compassion. I believe in the everyday people working in industry and operating industrial facilities. I’ve learned that we all have a very shared love for the community that we live in, and for the families that live here.”

In addition, her advocacy is supported through her own experience of being deeply engaged in her community. “Many people who grow up in communities like mine believe you have to leave home to succeed. But I think the most beautiful thing is to stay here, build here, and put down roots. I don’t need to leave to be somebody. I’m somebody because I’m here.”

“I’m in a transition from living on the southeast side of Chicago to being in college at Northwestern University, north of Chicago, in Evanston. I’m still near home, so I’m always trying to stay connected in both worlds. I’m very grateful for the people who have allowed me to grow as a person, as an organizer, and as a student. “

Colón, as both a witness and a participant, models civic engagement. Indeed, this photo essay, which documents the story of her community and her own personal evolution is itself a piece of civic engagement.

Employs a Structure

In “Slag Valley” images and words are placed in a specific order to develop a narrative that raises the reader’s awareness of the civic issue facing the author’s community, and the personal journey of the author as she articulates how she plans to grapple with this issue by remaining a part of the community she values.

With this in mind, the images and words are chosen and sequenced to illustrate both damage and resilience.

As you move through the essay, from introduction to conclusion, excerpts from the captions reveal this structure.

“The southeast side is a sacrifice zone for the city of Chicago.”

“I’ve learned that we all have a very shared love for the community that we live in, and for the families that live here.”

“Many people who grow up in communities like mine believe you have to leave home to succeed. But I think the most beautiful thing is to stay here, build here, and put down roots.”

“An important part of my community is that it holds so much Mexican life, culture, and joy.”

“But despite the industry that’s always in the background, we actually have a lot of parks and

green spaces to play in that are enjoyed by community members every day.”

“Healing requires more than me exercising my imagination, dreaming and visioning by myself. It requires me going out and sharing those visions with other people, listening to other people share their visions, asking them what they dream about.”

This narrative structure thoughtfully develops her civic argument, moving her audience from observation and understanding, to the urgency for action.

Related worksheet: What Makes an American Creed Photo Essay a Strong Piece of Civically Engaged Writing