A Teacher Inquiry Study Group Focuses on Racism and Homophobia

Are you ready to talk about homophobia? About racism? About other personal and political subjects? How about with your students?

Even the most open-minded and curious teachers might pause before answering those questions. They need a venue to test out ideas, time to sort through their own thoughts, and a space for discussion when dealing with personal and political subjects and introducing them into the classroom.

That was part of the thinking when the UCLA Writing Project applied for a 2003–2004 Teacher Inquiry Communities Network minigrant. Teachers and site leaders used the grant to start a project titled Collaborative Inquiry: Focus on Race and Sexual Orientation.

Taking On the Tough Issues

They formed two study groups, one focusing on each of what they saw as two pressing areas in need of attention at school: race and sexual orientation.

“Thinking, talking, and writing about issues of race and homophobia have enabled us to have conversations about realities that are rarely discussed,” said Faye Peitzman, director of the UCLA Writing Project and study group leader.

“Silence is the real danger—we remain ignorant, or just not knowing, and sometimes, particularly with issues of race, we bottle up thoughts until we explode. A lot of teachers don’t feel qualified to teach these subjects. But like anything else, you start small, and this is something that can be learned.”

Emphasis on Tolerance

Early on, the study groups recognized that these would be highly personal topics.

“Both groups provided very welcoming atmospheres, Peitzman said. “There was an acknowledgement of differences and we recognized that some conversations might be difficult. There wasn’t anyone putting someone else down for not being aware or lacking understanding. We provided a very safe place. The experience was new for everyone. Nobody understands everything about these issues.”

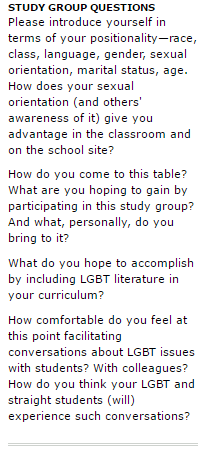

Conversations were constructive. The Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-Transgender (LGBT) study group, which includes straight, gay, lesbian, and transgender members, conducted focus groups among themselves, asking questions like “What are the advantages of your sexual orientation in teaching literature?”

Conversations were constructive. The Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-Transgender (LGBT) study group, which includes straight, gay, lesbian, and transgender members, conducted focus groups among themselves, asking questions like “What are the advantages of your sexual orientation in teaching literature?”

Gay and lesbian teachers shared a similar sense of their advantage, “a real understanding of what it’s like to be that child.”

Straight members’ sense of advantage had to do with acknowledgement of the power they have in the classroom. A straight male teacher who is urging equity, respect, and inclusiveness in the classroom will have an easier time of it; he cannot be accused of having a “personal agenda.”

A transgender teacher said his advantage was that as a teenager, when he was a girl, he experienced things teenage girls experienced. Now, as a man, he feels he has an understanding of both the boys and girls in the classroom.

“It’s a re-education for teachers,” Peitzman said, “in terms of their own curricula and how to be more inclusive and honor the backgrounds of all students.”

Time to Make a Difference

Soon, though, teachers moved from their own experiences and began asking themselves what they could do in the schools to make a difference.

The group focusing on homophobia undertook a project to introduce a new piece of literature into classrooms that expressed the thoughts of a believable gay teen character. The book they chose was The Perks of Being a Wallflower (Chbosky 1999).

The novel, written as a series of letters by a high school freshman to an anonymous friend, tackles a number of difficult issues for a high school audience—drug use, alcohol, sex, rape, suicidal thoughts. It was very popular among students. More than that, it got them talking about these issues.

“What shocked me was that students had conversations they had not had in other venues,” said Joel Freedman, English and journalism teacher at King/Drew Magnet High School.

Teaching the book with the support of the study group proved to be invaluable for the teachers. When Norma Mota-Altman introduced the book to her class, one parent was very upset that the students were reading the book and discussing these issues.

Mota-Altman turned to the group for advice, and they told her about a law called the California Student Safety and Violence Prevention Act of 2000, enacted to protect students from discrimination or harassment based on sexual orientation or gender identification.

“I talked to the parent about the law,” said Mota-Altman, an ESL teacher at San Gabriel High School. “I said my goal is not to push an agenda. It’s California law to create safe spaces in the classroom.”

Getting the Word Out

The leaders of the study group presented their findings at the 2006 NWP Annual Meeting to teachers interested in pursuing a similar course of action in their own classrooms.

“All of the teachers were enthusiastic,” said Mota-Altman. “They’ve thought of this issue, but didn’t know how to open the space to have these conversations. They were grateful for the ideas we gave them and that we shared our own experiences. A majority of teachers want to break the silence. Now they’re searching for a way to open the door.”

The Minigrant Connection

Members of the group acknowledge that the minigrant offered by the TIC Network four years ago got the ball rolling on this important work.

“Certainly the funding is helpful, but it’s the commitment that propels you to do it,” said Peitzman. “Everybody is so busy. Minigrants are a wonderful opportunity to do something that is really significant without waiting a year or two years to get things attended to. The application pushes you to be precise. What we’ll do. How we’ll do it. It forms the blueprint.”

Though the minigrant cycle of work was completed in August of 2004, the study group is still meeting, has started writing a book about their experiences, and may also produce a handbook about how to teach issues of sexual orientation, including resources such as the “Very Short List” LGBT bibliography, an annotated bibliography of literature, websites, and movies with LGBT information, characters, and themes.

“The grant dictates six meetings, but we keep meeting,” said Freedman, now a member of the TIC Network leadership team. “We just take off summers. Everyone has a vested interest in what we’re doing.”