Index

What is it?

Learning to set personal goals and reflect on progress toward them is a vital life skill, and when we give students the opportunity to set goals for themselves, we provide them with the opportunity to learn and develop that skill. And as writers develop, the goals they set can develop, too. For that reason, having students set goals for themselves as writers is a good practice at any grade level.

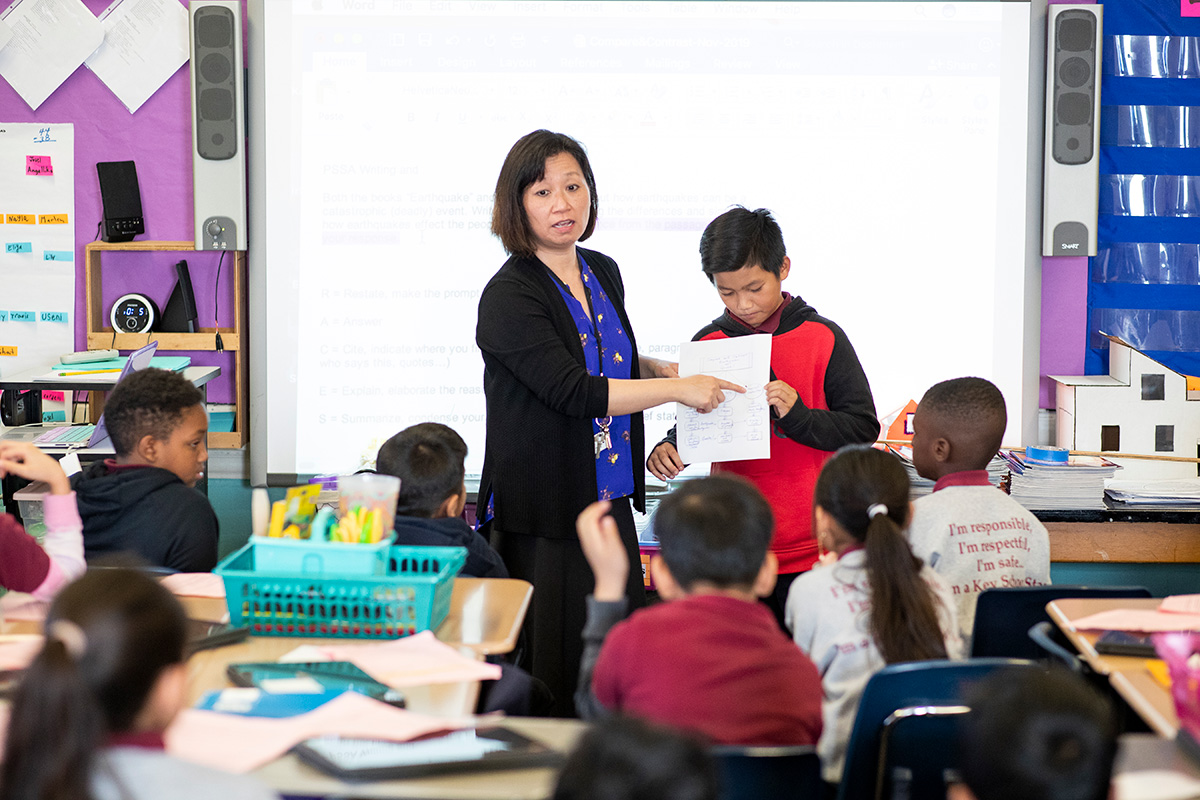

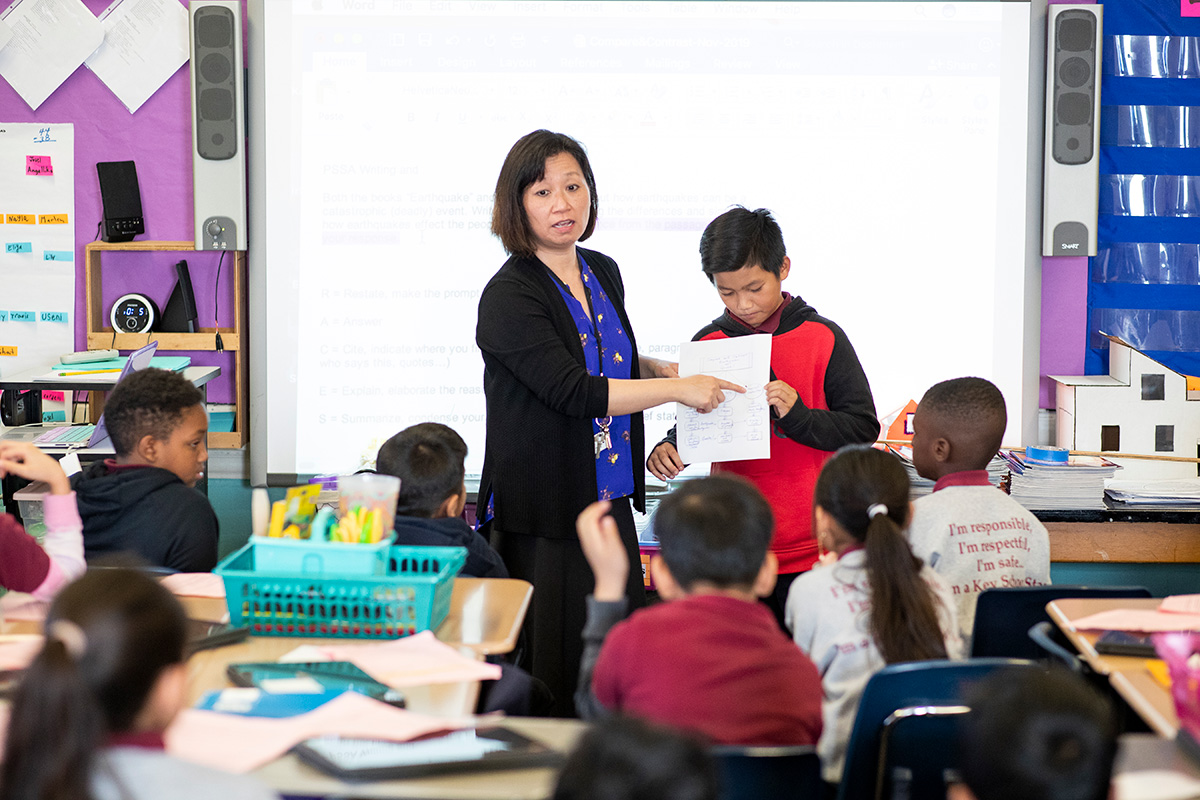

Students can set their own goals for writing as well as create goals collaboratively during writing conferences with the teacher or with peers, and those goals can become a point of reflection throughout the course.

Writing goals can be behavioral or strategic. For instance, students may want to work on managing their time or resources, or they may want to be able to write better sentences or more interesting leads. For other students, learning to maintain focus or develop fluency might be important. And, as students develop their own goals, they are also invited to consider what evidence they might examine to see if they are making progress.

Why do it?

Several meta-analyses of research on teaching writing show that helping students to set writing goals is a research-based way to help students improve their writing. Planning and goal-setting help to shift the responsibility for the writer’s growth from the teacher to the writer by asking the writer to decide how they want to grow and change as a writer, and to make plans for how to do that, promoting self-reliance, independence, and autonomy. When students set their own goals as writers, teachers and peers can adopt constructive roles as respondents and thinking partners.

How can I incorporate this into my teaching?

A wide variety of common activities can be adapted to support goal-setting in writing and support students to set, monitor, and achieve their writing goals. Here are some writing activities that align with goal setting:

- Personal Writing Vision Board: Have students create a vision board centered around their writing goals. Provide them with magazines, art supplies, and access to digital resources. They can cut out words, phrases, and images that represent their writing aspirations and paste them on a poster or in a digital format. This visual representation of their goals will serve as a constant reminder and inspiration throughout the year.

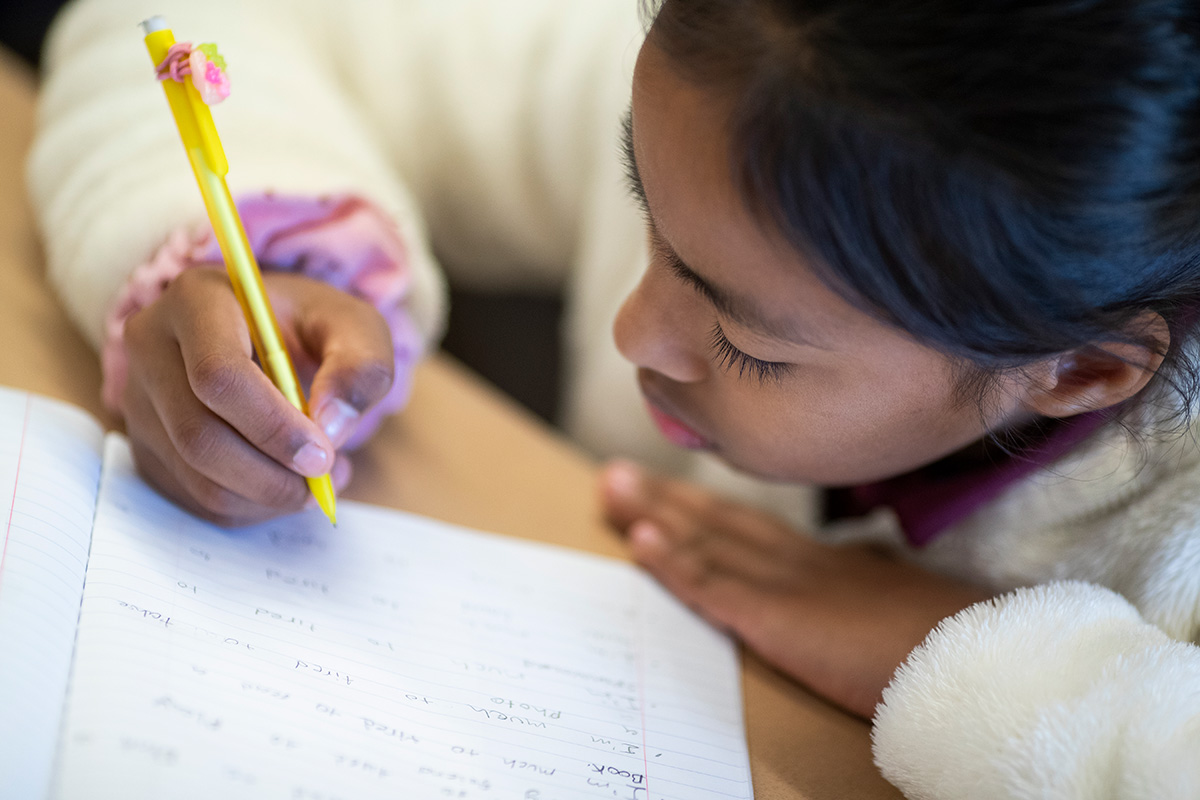

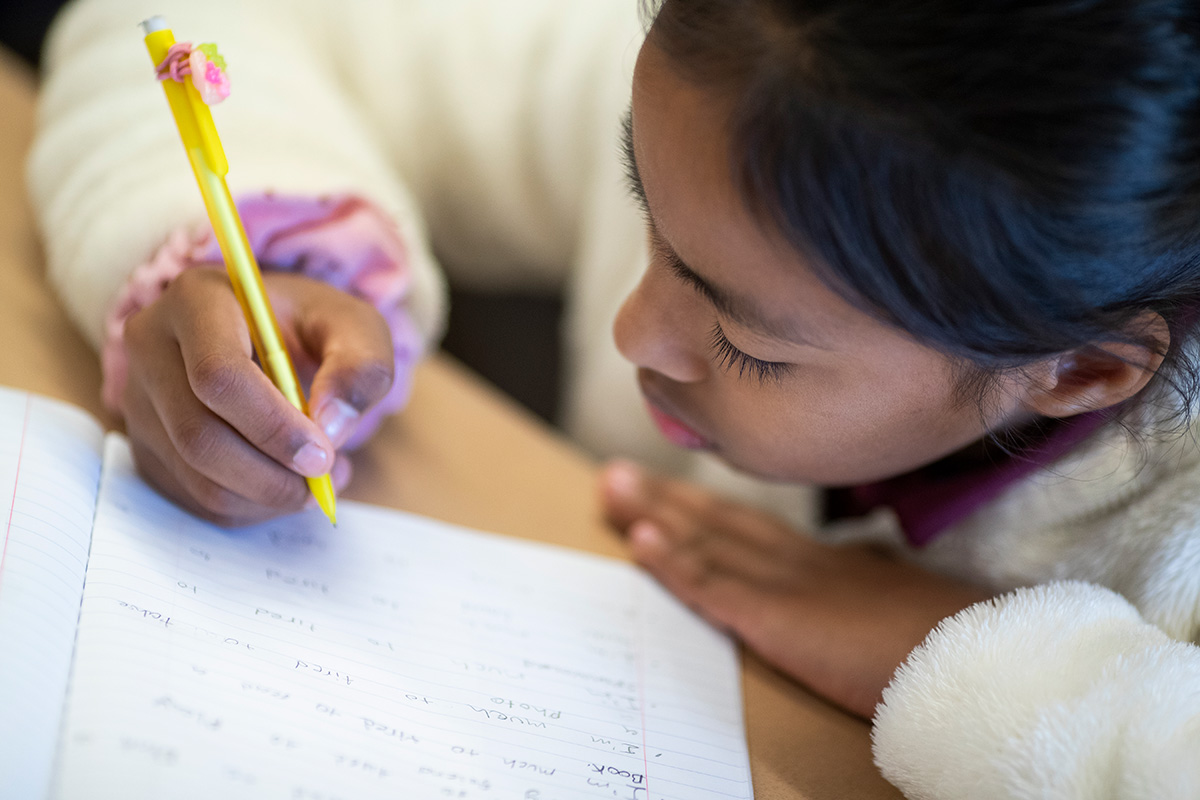

- Goal-Setting Journal: Give students writing journals dedicated to goal setting. Instruct them to write down their specific writing goals, along with action plans on how they intend to achieve them. They can also jot down their reflections, obstacles they encounter, and strategies to overcome challenges. Encourage them to use the journal regularly to track their progress and celebrate their achievements.

- Letter to Future Self: Ask students to write a letter to their future selves, which they’ll read at the end of the school year. In this letter, they can articulate their writing goals and express their hopes and expectations for their progress. This activity encourages reflection and provides an opportunity for self-assessment and growth.

- Goal-Oriented Writing Projects: Design writing assignments that align with individual goals. For example, if a student’s goal is to improve their descriptive writing, assign a descriptive essay or creative writing piece. Tailoring assignments to students’ goals—or allowing them to choose and frame their own assignments—makes the writing task more meaningful and relevant to their personal growth. Linking goals to student-designed assignments fits well with classes that use choice boards or student proposal processes.

When we invite students to set their own goals as writers, it’s important to honor those goals and treat them as meaningful. In many classrooms, that means that formal processes for reflection, feedback, and even assessment should incorporate students’ goals as well as teachers’ goals. Consider building processes such as these into your classroom routines.

When we invite students to set their own goals as writers, it’s important to honor those goals and treat them as meaningful. In many classrooms, that means that formal processes for reflection, feedback, and even assessment should incorporate students’ goals as well as teachers’ goals. Consider building processes such as these into your classroom routines.

- Progress Reports and Peer Feedback: Periodically, have students create progress reports on their writing goals. They can analyze their achievements, challenges, and adjustments made to their strategies. Additionally, consider incorporating peer feedback sessions where students share their goals, progress, and receive constructive input from their classmates.

- Goal-Setting Conferences: Conduct one-on-one goal-setting conferences with students. These conferences provide an opportunity for you to understand each student’s aspirations, provide personalized guidance, and track their progress closely. It also shows students that you are invested in their growth and development as writers.

- Journal Review Activities: In classrooms where students keep journals, such as the goal-setting journal described above, teachers can incorporate periodic review activities where students review their journal work with goal-focused questions in mind, perhaps annotating or highlighting passages that are relevant to them. These periodic reviews can become the basis for a self-assessment later in the course.

- Goal Celebrations: Set up a system of goal celebrations in the classroom. When students achieve a writing milestone or make significant progress towards their goals, celebrate their achievements.

In allowing students to set, plan for, implement, and monitor progress on their own goals, you can create a supportive environment that fosters self-directed learning and intrinsic motivation in writing. Students will develop a stronger sense of responsibility for their writing development, leading to increased engagement, a sense of ownership and responsibility for their own writing, an understanding that writing is a complex process of decision-making and problem-solving, and higher achievement in their writing goals.

“What if a school classroom space sometimes worked more like an interactive science museum — where the materials and environment encouraged informal learning? And what if field-trip and science-museum experiences sometimes worked more like the National Writing Project network — where people are the biggest resource, and collaborations are reflective and fluid?”

– Lacy Manship, Associate Director, UNC Charlotte Writing Project

The best of formal and informal education merged when the National Writing Project (NWP) and the Association of Science-Technology Centers (ASTC) kicked off the Intersections Initiative, a program to support partnerships between NWP sites and science museums around the country to integrate literacy practices with science, technology, art, engineering, and mathematics (STEAM) education and to work at the intersections of formal and informal education.

Why Bring Science Centers and Writing Projects Together?

Inverness Research had worked with ASTC and NWP for over twenty-five years, and Mark St. John thought there was tremendous potential in fostering this partnership for several reasons. One reason is that NWP and ASTC share a long history of working with science educators and youth. In addition, there are approximately 200 local NWP sites located across the country and over 350 science centers and museums that are ASTC members; many communities have both. All three organizations thought that a collaboration between the NWP and ASTC sites seemed likely to foster and be able to support innovative experiments in science-literacy work at scale.

Foundational Ideas

Several key ideas were foundational to the design and implementation of the Intersections project. First, it is both feasible and productive to have writing project sites and science centers plan locally appropriate, innovative science-literacy projects. Rather than setting out to dictate that local partnerships would implement a “one-size fits all” program, the Intersections project would provide guidelines and ongoing input to help foster the creative bubbling up of innovative ideas from local sites. Another key idea is that the project would focus on the formation of partnerships first, developing projects second, with the forming of project ideas as a vehicle to build partnerships within the network. The Intersections project would also focus on design and iteration, using multiple mechanisms to provide the local partnership sites with a variety of input and feedback on the design and implementation of their local programs—including design institutes and charrettes, community calls, leadership team thinking partners, and annual reflective report writing processes. In addition, the Intersections project was designed to address the challenge of how to scale up and disseminate local, innovative programming: by linking two national organizations in this proposed project, with their history of sharing programs and practices across both kinds of communities (writing and informal science learning), this project would create the opportunity for both large-scale experimentation and dissemination of creative arrangements between NWP sites and science centers. These small local experiments, networked together and supporting each other, could lead to innovative designs of programs and activities that give informal and formal science educators skills in developing science and literacy programs, and give youth creative opportunities to have rich science inquiry experiences while at the same time fostering literacy and media skills.

Symbiosis: Innovation and Scale-Up

The huge existing capacity to share and disseminate these experiments through both of these existing organizations—essentially continually growing the network of NWP sites and science museums involved in the effort —could provide a mechanism that creates a symbiotic relationship between innovation and scale-up.

The resulting Intersections project’s goals were to create partnerships between NWP sites and science museums, to support their self-identified science and literacy programming, and link them with other sites across the country through professional development and technical assistance activities to create a network of practitioners that share and communicate emerging new practices. Led by project leaders from both NWP and ASTC, Intersections would help broker local partner arrangements between NWP sites and science centers; provide meetings and ongoing support mechanisms to enable these partner sites to share ideas and learn from one another; provide technical assistance and evaluation of programming efforts; and ultimately, produce a collection of successful arrangements and program designs.

What is a field trip for?

A field trip is a ritual of the school year. But for many, the traditional model of the field trip is not working. Increasingly teachers are feeling pressure to justify the costs, especially in schools that are strapped financially, as many serving low-income students are. They rush from exhibit to exhibit to see everything. But with museums, sometimes less is more.

A child who is engrossed by an exhibit of reptiles should not be nudged along to the next exhibit by the dictates of a worksheet and time clock.

“It was heartbreaking to watch the student who was mesmerized by a particular artifact be pulled away in the interest of time,” said a San Diego teacher who took part in a weekly meeting of educators and museum staff. “What is lost when students get the message that quick and complete [as in forms] is what is valued?”

The weekly meetings were part of the Intersections project, which brought together teachers from the San Diego Area Writing Project at UC San Diego, educators in the city’s public schools, and staff from two local museums, the San Diego Natural History Museum and the Fleet Science Center. Together, they wanted to rethink the field trip.

Scientific Inquiry

In a series of “field trip pilots,” the Intersections team sent teachers, students, and staff to wander the National History Museum, and as in a proper science experiment, observed them in their natural habitat. It was transformational.

Using the materials and practices developed by the local Intersections team, public school teachers would bring students to the museum. While the students were in the museum, teachers and museum educators observed the students and chaperones in action—but did not interact with them. This allowed them to focus on how students interacted with the exhibits, the adults in the room, and each other. They snapped photos of the teachers and students, and they created a map of the spots where kids interacted with exhibits. Some researchers followed a single student, while others stayed in one section of the exhibit and watched students there. Examples of these teachers’ field notes can be found here and here. Stepping back to see the students through the lens of a researcher helped to remind the teachers of their goals for students beyond the trip itself.

The field trip pilots also allowed for iteration. The Intersections team was able to test the tools they were developing, find out what was and was not working, and redesign them accordingly.

Findings

So what did the Intersections team learn? First, students do not need more worksheets, and teachers do not need more printed museum guides. Instead, teachers need support in thinking through their goals for a field trip: What do they want students to do as a result of their museum experience? Once that is clear, teachers can prepare students for the visit.

The team also learned the value of partnerships across institutions. Without such a meeting of the minds, they discovered, shared misconceptions would have led them right back to worksheets.

Before the collaboration, the museum educators had assumed teachers wanted guides and worksheets for their students with standards highlighted for each exhibit. Teachers, meanwhile, had assumed museum educators wanted them to use guides.

The new approach allowed teachers and museum curators to explore content and curricular goals together. And, most importantly, it created space for the two groups to talk about how to best support students. Museum educators learned about the barriers teachers experience in scheduling and planning field trips and the misconceptions and lack of information that keep teachers and their students away from museums. In the end, both sides realized that less is more. Just because you can get to all the exhibits at two museums in one day doesn’t mean that you should.

Project or Partnership?

Four of us sat at a table in Denver, Colorado, unsure how to continue. A team of Boiseans from our local Writing Project site and science museum, we were tasked with working together as part of the National Science Foundation’s Intersections grant, an investigation into the overlap between science and literacy. We had just embarked on this partnership–or so we thought–at this planning meeting and were already experiencing nuclear fallout. Our exciting idea for a joint venture was in shambles.

Earlier that day, we enthusiastically jumped into planning a specific event: GameFort. The idea was solid; we knew where and when it would take place and how it would enhance Boise, Idaho’s wildly popular TreeFort festival. We even mocked up a logo. Then with a stroke of luck, which at the time felt demoralizing, our grant team’s thinking partner asked us some tough questions and everything fell apart. We had become so engaged in co-planning a specific project that we didn’t recognize it was holding us back from the real work of the grant: building a sustainable partnership. What now?

We had put the cart before the horse. Starting a partnership by focusing on a specific project is attractive and “easy” because it engages you in something concrete and feels productive. However, this approach is limiting and misses the real purposes of collaboration. Eventually, questions arise (or go completely unnoticed) about sustainability, long-term goals, and how your organizations might develop a true mutually-beneficial partnership and grow together through shared inquiries.

Sustainablity

As we sat around the conference table trying to regroup, we realized that we had neglected to build a foundation for our working relationship. It was game over for GameFort, and we ventured into the abstract by asking ourselves some essential questions. Who are we as organizations? What are our values? Who do we serve? What do we want to learn together? We grabbed markers and chart paper and started mapping this conversation. In this moment we began making the crucial shift from the tangibles of project planning to the more intangible and meaningful: a sustainable partnership.

Back in Boise we continued by learning more about one another’s contexts, which influence so much of what anyone does and how they do it. Typically we planned at the science museum, the Discovery Center of Idaho (DCI), where we staged our programs for teens and teachers. By spending time where the event took place, we could see for ourselves how an activity would play out and keep abreast of DCI’s ongoing remodeling project. If there was a centrally located school or classroom available, we would have also planned there to better consider teacher and student experiences in formal learning spaces.

The Importance of Inquiry

Another interesting factor that contributed to the developing partnership was a change in personnel for DCI and the Boise State Writing Project (BSWP). Between the first and second year of our partnership, both organizations incorporated new members into the grant team. We inquired about ourselves and the intersections between our organizations by revisiting some of the questions below. This served the immediate purpose of orienting the new team members, and also helped everyone reach deeper shared understandings about the nature of our partnership.

● What is your organization’s mission? If your organization already has a mission statement, what would it be in your own words?

● What are your organization’s most important values?

● What are your organization’s goals? What actions help you meet those goals? ● Who does your organization serve?

● Who does your organization want to serve or know more about? ● What is a story of your organization’s work that your partner needs to know? ● How could this partnership support your organization’s goals?

● What expertise or resources do you bring to the partnership?

● What do you think your partner expects to receive or gain?

● What would happen if you were not partnered together?

In for the Long Haul

Sustainable partnerships work when organizations are interdependent and pursue common interests. In year one of our Intersections grant work, we conducted a week-long inquiry into the needs of teens and science teachers–two groups we want to better understand and serve. Our teen participants generated innovative ideas that resulted in exhibit changes at DCI. Our teachers primarily served the teens. Consequently, we yearned to learn more about their needs. Pursuing those shared questions about groups that we want to serve helped both organizations learn things they would not have learned in isolation.

In the second year, we made a conscious decision to shift the focus of our inquiry and designed a year-long fellowship program specifically for teachers. This inquiry not only served our teacher fellows but inspired the staff at DCI to redesign their approach to field trips and to working with teachers in general. Teacher Consultants with BSWP drew from the resources created during the second year of the Intersections partnership to inform professional development with teacher leadership initiatives the following summer. These kinds of shifts in direction are only possible when there is a clear understanding and empathy between organizations because we were keenly aware of one another’s strengths and interests.

Beyond the formal work of the Intersections grant, BSWP and DCI have collaborated on other professional development projects, continue to meet and learn in each other’s spaces, recently presented at a statewide conference, and share announcements and promote initiatives for each other. We attend each other’s events and regularly meet to plan for the future. We wonder about how best to meet the ongoing professional development needs of science teachers and finding new ways to explore the intersections of formal and informal learning spaces. Our organizations continue to pursue important questions collaboratively because we are invested in our partnership and in growing together.

Bell Ringers are not a new invention—I can remember trading lists of bell ringers even as a new high school teacher in Maine many years ago. They serve a practical purpose for many teachers who create, adapt, or steal a variety of assignments to keep students busy while they deal with attendance and other housekeeping.

The practicalities of bell ringers are to bring focus and fill time and to help students get settled and ready to learn, but of course, they can also be so much more. The ‘so much more’ came to me again as I was reading Deanna Mascle’s blog Metawriting. Deanna, who describes herself as a Writing Evangelist, writes about the way she uses bell ringers to create a classroom writing community with her college-level composition students. The more I read, the more I saw her purposes in using them, starting with building community and writers’ identity.

Deanna on Community Building:

My name is ____ and I am a writer from…

(Borrowed from Richard Louth, founder of the New Orleans Writing Marathon

and Director of the Southeastern Louisiana Writing Project)

For the past three semesters, this is how I begin every in-person class – deploying this simple question. As a community, we write this sentence into our journals (filling in the blanks) and then write. At the beginning of the semester, I offer the explanation that from can be a place or a state of mind; then as the semester progresses as we know each other better I ask:

How are you?

What is heavy on your mind or heart today?

This simple exercise is a powerful move as it grounds us in our purpose (I teach writing after all) and the moment (life offers so many distractions). Then we share what we have written. I expect every student to share although occasionally some will pass if their writing is too fraught, but I offer them choice about how much to share so they quickly progress to sharing more and more:

- Just share that initial sentence (My name is Deanna and I am a writer from contentment)

- Share the sentence and selected excerpts or explanation

- Read the journal entry in full

In most classes (especially at the beginning) I share first to model and help my students get to know me as a person. It also allows me to then focus on my students as we work around the room. I typically share my full journal entry because I am a writing project teacher accustomed to sharing my writing. I know that as a human I usually look forward to these writing sessions and as the semester progresses more and more of my students tell me how much this moment of introspection and community means to them. Listening to a recent interview with Dr. Gabor Maté about his book The Myth of Normal reminded me again of the power of writing to help us cope with stress and trauma. I think that is one reason this practice is so meaningful to us as humans. But as a writing project teacher, I also know there is power in the regular ritual of writing and saying the words: I am a writer.

As a teacher, this simple check-in process is beneficial in so many ways. It allows me to take attendance without taking attendance, but more importantly, it helps me match names and faces as well as learn students’ preferred names. Even more important it helps me know my students. Since beginning this process I have developed a much better understanding of their physical and emotional state (collectively and individually) during the rhythm of the semester and this challenging period in their lives (first year in college). I never regret the time we spend on this practice but, full disclosure, I do teach a 75-minute class so I have the time to do it every meeting. Last, but certainly not least, I love the powerful writing that emerges in these quick writing sessions and being able to point to that writing when students tell me in moments of frustration that they are not writers. This practice not only requires students to say they are writers…it shows them that they are writers while demonstrating the power and magic of writing in human lives.

As I am learning more about my students, they are also learning more about each other. Students discover shared worries and fears, celebrate victories, and connect in countless ways. There is great power in learning that so many of their worries and challenges are shared and there is also a tremendous sharing of coping strategies and life hacks along the way.

Deanna on other purposes for bell ringers

Deanna’s post about community is not the only time Deanna has written about bell ringers. I love that she thinks not only about WHAT students are going to do in those first few minutes, but WHY. And her why’s extend beyond keeping students busy or getting the ready to learn and instead lean into a coherence of purpose across the class. Here are three more purposes Deanna offers that can help you make the most of Bell Ringers in your class.

Create a Focal Point

Kicking off each class with a targeted writing prompt underscores the theme for that day’s class. It makes clear to everyone what we are going to focus on that day. Posting the prompt before the start of class and establishing the practice of students writing at the start of class makes the transition into class time easier for everyone. After only a few classes, students easily fall into the pattern of settling into writing without prompting. Finally, thinking and writing about the prompt helps both teacher and students get our heads into the game. The practice gives us time to gather our thoughts and access our existing knowledge about the topic so that when work began in earnest we were ready.

Fuel Discussion

Bell ringers tie directly to the topic of the day. This strategy means that when the time comes for the class discussion everyone has something to say. Spending time writing about one or two specific ideas or questions before a discussion ensures that everyone has some thought to contribute to the conversation. As an example, ask students to sum up their writing with a six-word story before transitioning from bell ringer to class so students have the option to share selections from their writing or their six-word story (with explanation). As students become comfortable with the bell ringer model I need to prompt less and talk less during our class discussions.

Jumpstart Assignments

Jumpstart writing assignments with two or three successive bell ringers. Students feel much more confident about their ability to succeed with an assignment after they have already written hundreds of words on a topic. Also, there is a lot less struggle about selecting a topic or focus for an upcoming assignment if we have already explored possibilities through bell ringers paired with discussion.

When we invite students to set their own goals as writers, it’s important to honor those goals and treat them as meaningful. In many classrooms, that means that formal processes for reflection, feedback, and even assessment should incorporate students’ goals as well as teachers’ goals. Consider building processes such as these into your classroom routines.

When we invite students to set their own goals as writers, it’s important to honor those goals and treat them as meaningful. In many classrooms, that means that formal processes for reflection, feedback, and even assessment should incorporate students’ goals as well as teachers’ goals. Consider building processes such as these into your classroom routines.