Curators notes:

Students in Washington State face the rigorous expectation of 24 credits to graduate from high school. For students whose learning is disrupted by trauma or who don’t find relevance in their academic courses, even one failed class puts them at risk of dropping out. This summer program helps students make connections between a dream job and the academic standards they need to graduate.Summary:

Educators in the Lake Stevens School District in Washington give students the chance to earn failed credits over a three week program by pairing project-based learning with students’ own career ambitions. Included are samples of student work and PBL student surveys.It started with a snowstorm and survived a pandemic. A rare snow day sabbatical let a group of teachers troubleshoot an outdated credit recovery system. Instead of our high school’s packet-heavy approach, we hoped to give students the chance to earn failed credits by pairing project-based learning with their own career ambitions. Because project-based learning encourages skills across disciplines, students might even be able to earn multiple credits for a single project. If it worked, we could help students rekindle their passion for learning and build connections with local mentors.

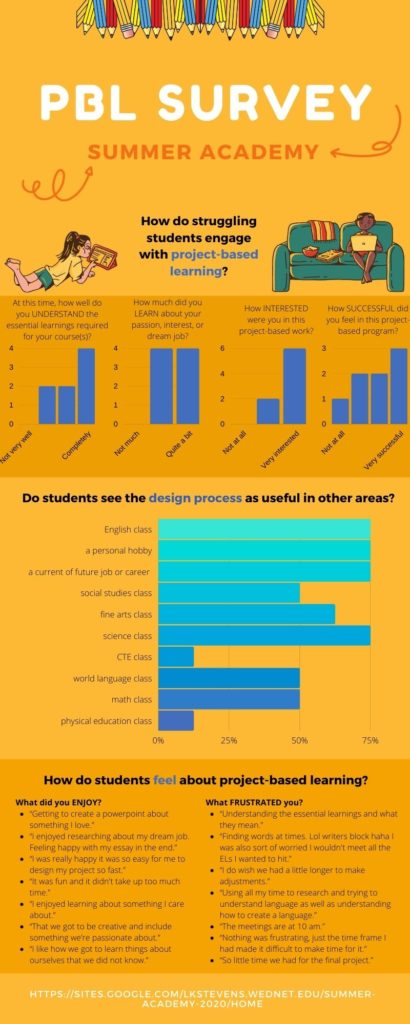

The plan, for ourselves and for students, was guided by the design thinking process:

EMPATHIZE: Designing for students

Our inspiration was our students who are uninspired by traditional school. You know that kid who’d rather not work in your class? Maybe she’s more focused on her sketches. Maybe he’s always Googling new sneakers. We know these kids have passions — their interests are apparent in the ways they choose to spend their time. It’s just that not all interests have a clear home in a traditional academic setting. How can Algebra 2 compete with the new Jordan sneaker drop? Our mission was to design approaches that would let students see connections between their passions and the essential learnings required to graduate.

Through support of John Legend’s Show Me Campaign, the National Writing Project, and the U.S. Department of Education, the Educator Innovator Grant allowed us to plant seeds for a project-based ecosystem in Lake Stevens School District. We intentionally layered our goals to maximize impact on students. By training teachers from core content areas and using their expertise to build a credit recovery program, we spread interest in project-based learning across multiple buildings and disciplines while supporting specific students in a project-based summer school.

DEFINE: Building a PBL foundation

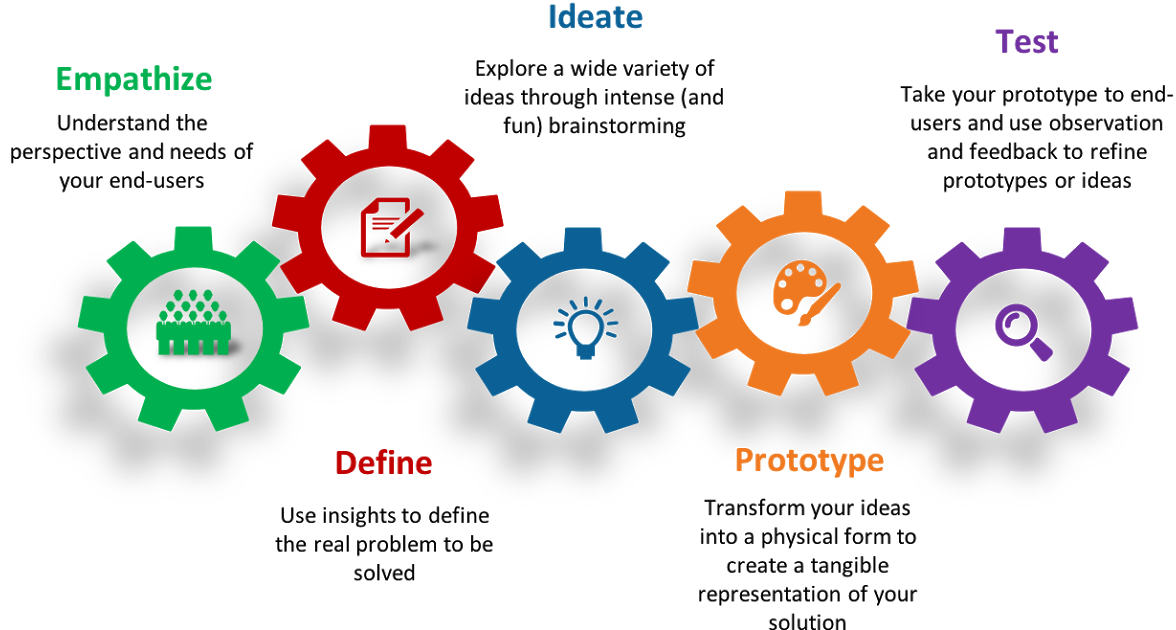

In August 2019, we hosted Nick Provenzano, author and Technology Coordinator and Makerspace Director from University of Liggett School in Michigan, to train teachers in project-based learning and design thinking. Nick’s guidance made it clear that well-designed project-based learning can engage students who might not thrive with traditional assignments while challenging students who have mastered the “game of school.”

The grant team with Nick Provenzano.

For teachers new to PBL, excitement was mixed with “yeah, buts.” We realized:

- PBL takes time. What can we realistically cut to make time?

- PBL relies on deep content knowledge from the teacher.

- It’s important to prepare kids to be open-minded.

- Learning can also happen during student presentations and discussions.

- Success seems to stem from relationships and student passions.

Teachers designed duct tape wallets to learn the design thinking process.

Although we had planned for teachers to spend time building PBL units only for their own classes, Josh, a social studies teacher, pointed out that “I don’t get the chance to work with these great colleagues very often.” He proposed we work together to brainstorm PBL topics that could help students learning and demonstrate skills in multiple content areas. Thirty minutes and a shared Google sheet later, we had 28 project topics with suggested driving questions and content-area skill alignments for each. We had the foundation for PBL credit recovery.

PROTOTYPE: PBL in our classrooms

The seeds planted in this PBL training took root during the school year. Joel’s 20 Time project was a hit with kids. Spending every Friday researching and building on topics of their choice, students found connections between their interests and social studies content. One of his students was looking up mysticism and astrology when she should have been researching Renaissance history. He talked with her about how interesting the topic is and how that could be a good fit for her project. “Really? I could do that?” she asked. “I hope you do!” he said.

In my English class, students were challenged to write a play about abuse of power inspired by The Crucible. Hagen, a junior who is more interested in diesel engines than literature, asked, “Could we work together as a whole class?” I told him, “It might be really complicated, but you could!” Immediately, he stood on his chair (a la Dead Poet Society) and asked for volunteers. Most of the class stood, one by one, as he talked them into it. Those who remained independent had ideas for writing their own plays. Miki wrote about rape on college campuses. Zoe wrote about an abusive boyfriend. Nyah wrote about indigenous communities being burned out of the Amazon Rainforest. By gaining the freedom to explore their passions in this project, they were excited to create.

Students perform their original play about abuse of power.

TEST: Getting student feedback

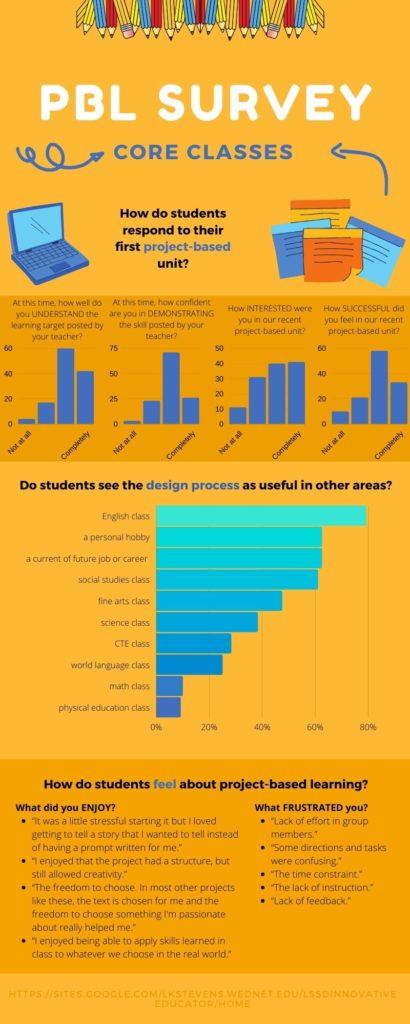

After their first PBL unit, 124 students completed a survey about their learning experience.

We confirmed that students enjoyed the freedom to choose relevant topics and saw the value of design thinking across content areas. We responded to student frustrations by becoming more intentional with structure and feedback through the design thinking process.

IDEATE: Building momentum

Our grant team went on to lead a professional development workshop introducing teachers to benefits, structures, and scaffolds of project-based learning. We also facilitated PBL curriculum development with chemistry and physics teachers. With all this support, six English teachers collaborated to build a new project-based unit around Joy Luck Club, and at least three additional teachers added 20 Time projects to their classes. One of these was a sophomore science teacher who commented that when learning switched to online during the initial COVID shutdown, it was the 20 Time projects that continued to engage his students with voluntary learning through the end of the year.

Plans for our summer credit recovery program were developing as well. In collaboration with teachers, counselors, administrators, and instructional coaches, “Summer Academy” took shape. We developed a curriculum, advertised the opportunity to students and families, and recruited community mentors.

(Re)PROTOTYPE: Surviving a pandemic

When schools shifted online during the pandemic, we saw an increased need for Summer Academy; students whose grades were “incomplete” at the end of this year would need a quick way to recover credit.

We got to work adapting Summer Academy for remote learning. We built a website for teachers leading this summer’s pilot and similar PBL projects in the future. We realized we had a new opportunity for asynchronous support from content-area experts and community mentors: Flipgrid, emails, and increased attention to our need amid the pandemic made connections between students and mentors more flexible and rewarding. But we were nervous about keeping students engaged online if they already struggled with online learning during the school year.

LAUNCH: Summer Academy pilot

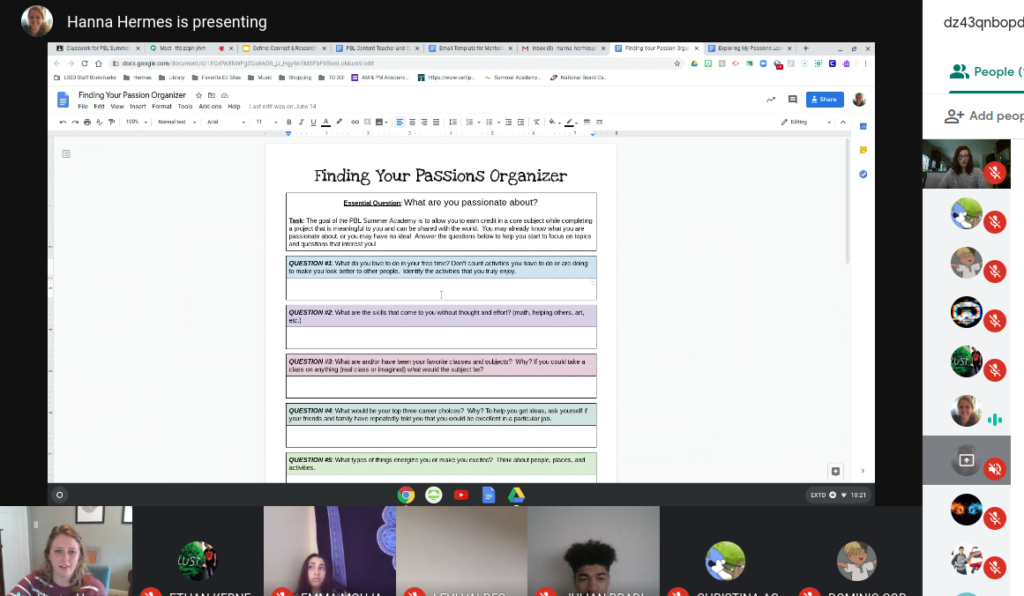

In the last week of school, counselors got increasingly excited about Summer Academy, especially when it became our district’s only summer school option. After recruiting and communicating with students and parents, we registered 12 students for the pilot. Their goal was to demonstrate essential learnings for failed courses through a project focused on their hobby or future career. Hanna, our program’s teacher, facilitated class using Google Classroom and Google Meet. Students would also get help from community mentors with expertise in their area of interest. With a shorter time period, focused goals, and plenty of individual support, students who did not have the stamina to complete a semester course could sustain momentum for three weeks.

Summer Academy via Google Meet.

As students developed their project proposals, we went from seeing “I don’t know” in vague drafts to hearing “I can do that!” Reviewing expectations, providing product examples, and getting immediate feedback for project pitches helped students feel more confident. Hanna’s candid and caring attitude won students’ hearts as they tackled ambitious projects.

- Emma—an energetic student who was reluctant about pairing math with theater in her project—became enthusiastic when we suggested she make a budget for what it would take to live as an aspiring actor in LA or New York. This project will let her actually envision living out her passion while applying essential math and research skills.

- Ethan wasn’t sure how to create a project around drift cars until we encouraged him to record himself guiding a drift car build using a video game. He went away excited to get started.

- Ashton—who had the most “don’t know” responses in his proposal draft—started to show off his expertise when we encouraged him to make a video explaining how and why to build fingerboards out of specific materials and shapes. “There’s actually a lot that goes into these things: decks, bearings, angles…” he said as he showed us the many boards he has built at home.

- Julian, a former football player who needs to make up six classes, shyly suggested he’d like to invent a language.

- Serenity will be writing a short story about geometric shapes in marine biology: “There’s actually a lot of math involved in marine biology,” she explained. “And I like to write stories.”

- Mountain biking, quad tracks, dirt biking, an infographic comparing the impact of COVID-19 on immigrant and privileged communities, and an original song about the most efficient learning process were also among project proposals that then went on to get feedback from community mentors.

At the end of our three-week program, 11 out of 12 students earned credits in a combined total of 23 classes. Two projects stood out from the others. The first is Dominic who was recovering credit from English and a science course. He took the ideas needed for the essential learnings of those courses, did some research, and transformed his learning into song lyrics. His submissions for the final project were the draft sheet of his lyrics and an MP3 of his performance.

Another standout project was Juliana whose career passion is cosmetology. She had already graduated and the credits she recovered allowed her to complete her requirements and go to cosmetology school. She took her interest in achieving the perfect look and developed a study on Makeup Over the Decades where she researched the makeup of famous women beginning in the early 1900s through the present. She analyzed what made each woman’s look unique, had a photo of that celebrity, and took a selfie replicating that style.

TEST: Getting student feedback

At the end of Summer Academy, eight students completed a survey about their learning experience.

Though the size of the pilot and survey were small, we saw greater confidence and engagement with project-based learning. We achieved our goal of helping students create connections between their interests and the essential learnings they need to graduate. The most common feedback from students was requesting more time; most suggested an additional week for this summer program. We were pleasantly surprised that students would have been willing to extend their summer school experience to work on a project they cared about.

Students’ ownership of the process was astounding. It’s every teacher’s dream to have students engage with learning and have their own novel connections to ideas. To achieve this dream among students who failed traditional classes was especially rewarding. Beginning with students’ own interests provided traction when a typical learning environment seemed less relevant. Student enthusiasm was obvious even to those on the outside. One community mentor commented that he was very impressed with the level of understanding his students had demonstrated and that he had learned something himself about their chosen topics.

REFLECTION: Learning from design thinking

Many summer programs were canceled by the 2020 pandemic. We were relieved that ours proved flexible enough to transition to remote learning. In fact, the online-only adaptations made it more accessible to community mentors who could interact with students via email without taking time off work. We realized early on that this program teaches students to advocate for themselves and communicate with adults. By scaffolding their emails to teachers and community mentors, students communicated professionally and got quick responses. With a smaller class and with remote instruction, they discovered that asking questions is a vital part of the learning process, not an extra step or an indication of failure. If they leave the program with this skill, they will be more prepared for future classes and careers.

Some lessons, however, would be more efficient in person. Our summer facilitator Hanna believes that, face to face with students, introducing project-based learning could be reduced to one day rather than the bulk of the first week. For students who are typically told how to think about topics, reorienting to learning through their passions was a greater challenge when so much of that learning had to happen independently at home.

Another challenge was that several of our students got day jobs that interfered with the scheduled time of the program. Hanna generously held a second meeting in the later afternoon to support four students who had this complication. In the end, a new full-time job was the reason the one student who did not complete the requirements was unable to do so.

The success of this grant-funded work has been an encouraging growth experience for all involved. Our professional development resulted in a shift in practice for many classroom teachers from traditional content-based to project-based instruction. We go forward with a tremendous number of supporting resources collected into a project-based learning website and a Summer Academy website to support teachers stepping out into the unfamiliar. This shift couldn’t have come at a better time as we reimagine how to engage students in a fully virtual learning environment during the ongoing pandemic.

Inspired by the success of this credit recovery program, one of our grant team members has established a non-profit organization to support non-traditional learning environments for students. This cooperative pairs experienced teachers with families who need help with homeschooling or remote learning, filling a critical need while our nation works through the effects of the pandemic.

Most importantly, the lives of eleven students were impacted by their experiences this summer. They rekindled a passion for learning, made positive connections with adult mentors in the community, and earned credits toward graduation. Our thanks to John Legend’s Show Me Campaign, the National Writing Project, and the U.S. Department of Education for seeing our vision and giving us the opportunity to develop and share this innovative approach to student learning.

Credits and Thanks

Grant writing team: Jody Cain, Kelly Guilfoil, Holly Urness

Project-Based Learning website design: Jody Cain, Holly Urness

Summer Academy website design: Jody Cain, Kati Tilley

Summer Academy teacher: Hanna Hermes

Curriculum advisory team: Tim Bartlett, Jody Cain, Kelly Guilfoil, Hanna Hermes, Kati Tilley, Holly Urness

Special thanks to our community mentors, content consultants, Summer Academy 2020 pilot students, and Lake Stevens School District administrative, counseling, and secretarial support.