A Picaresque Tale from the Land of Kidwatching: Teacher Research and Ethical Dilemmas

For the past ten years, I’ve been doing classroom action research and working in our Gateway Writing Project with teacher researchers. Action researchers, also called teacher researchers, take a systematic look at their own practices with the idea of improving them. Writing Project people are used to keeping journals, capturing a scene on paper through vivid, personal and social details, and sharing their writing with an audience. For our teachers, the NWP experience seems to lead naturally into action research—jotting field notes, gathering data from close observation or interview, and interpreting the scene in writing for other teachers. I believe in the power of action research for personal and professional growth. But as the National Writing Project becomes increasingly committed to this mode of inquiry, we need to look closely at the problematical issues raised when teachers study their own classrooms.

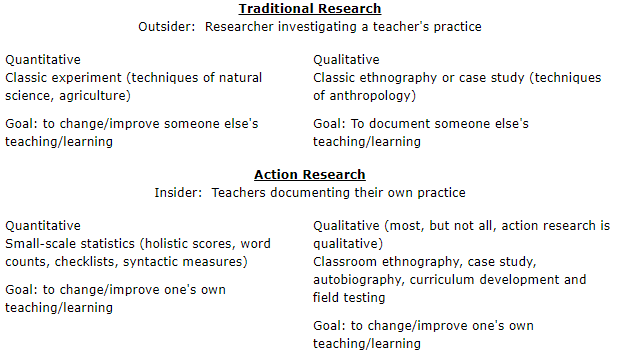

Classroom action research draws on the qualitative methods and multiple perspectives of educational ethnography. When our work is challenged or misunderstood by parents or administrators, we take pains to distinguish action research from traditional quantitative research: We explain that we don’t deal with statistics, control groups, or manipulated variables, but with the human drama as lived by self-conscious actors. Perhaps it is just as important to distinguish action research from traditional qualitative research: We aren’t outsiders peering from the shadows into the classroom, but insiders responsible to the students whose learning we document. The following chart illustrates these different modes of research:

Action research usually falls in the lower-right quadrant of the chart: qualitative research by insiders. A teacher-researcher may work alone or in collaboration with a team of colleagues, a seminar or an outside researcher. In any case, what is appropriate for traditional research may be inappropriate for classroom action research by teachers.

The ethical checks and balances used by the outsider doing a classic experiment (random selection, control groups, objectivity) are either irrelevant or problematic for us as teachers. If I’m working to improve my sensitivity to students of a different culture, and I’m gathering data on my efforts, do I really want a control group in which I must be culturally insensitive? In the same way, the ethical safeguards of the outsider doing qualitative research (anonymous informants, disguised settings) may divert us from the action researcher’s goal of open communication and collaboration with colleagues, students and parents. If my department has been working to improve the teaching of writing, and students have knowingly helped us by saving their drafts and sharing reflective journals, shouldn’t we name and credit them if we publish a report? Teachers researching their own classrooms can anticipate ethical dilemmas quite distinct from those of the outsider doing research, whether quantitative or qualitative.

I’ll introduce these dilemmas with a few stories from the experience of teacher researchers in the Gateway Writing Project. These stories emerged from discussions in the Action Research Collaborative in St. Louis and are meant to introduce the guide we have developed: “A Guide to Ethical Issues in Action Research.” ARC members are field testing this brief guide to share with others who may embark on a journey of classroom inquiry.

A Picaresque Tale

As an action researcher, I sometimes feel like a character from a picaresque novel—Don Quixote, Pilgrim’s Progress, Tom Jones, Candide, or even The Wizard of Oz. A picaresque tale takes us on an unpredictable, often bizarre set of adventures, wandering from place to place and from scene to scene, seeking a goal the hero may come to understand only through the journey. The tale I will tell here is episodic and bizarre, but true—a composite of the misadventures, crises and insights I’ve gained through five journeys with teachers doing research. All identities have been thinly disguised to enhance the story and reduce the risk of further misadventures. So come along, Dear Reader, as I begin my tale.

Scene 1

In the first episode, we meet a special education teacher working in a program for teenage dropouts under the auspices of the juvenile detention center. His job includes carefully documenting his sessions with the teenagers, their parents, counselors, and others. As a doctoral candidate, he chooses to expand that documentation into a view of the world through the eyes of his kids. Using rich details and the voices of the juvenile offenders, he shows how the simplistic explanations (“They never learned to value education”) don’t fit the reality of their experience (“Why do they cry when they tell me about dropping out?”) Midwest State University requires a “Human Subjects Review” of all potential research projects.

Our teacher-researcher faces the ordeal bravely, affirming that his subjects will not be given drugs or shock therapy, that all the data is being gathered in the normal course of his role as a teacher, and that, yes, some of the data deals with illegal acts and underage persons. The HSR is rejected. The Committee wants signed permission from the parents of all students to participate in the study and an exact script of the interview protocol!

The crisis is eventually resolved only through the intervention of a higher power, a well-published ethnographer who tells the dean of research that the HSR seems more appropriate to a traditional experiment than to a study documenting a teacher’s own practice. (The dean approves the proposal and suggests that faculty engaged in this sort of qualitative, insider research come up with a more appropriate Human Subjects Review document. The best of all possible worlds? Or the labors of Hercules? We’ll return to this quest and its outcome in good time. But now we must set off again on our journey.)

Scene 2

Our next encounter is with an earnest teacher educator, committed to reflective practice and eager to give her pre-service teachers a taste of writing field notes, interpreting, and reporting. Her assignment is simple. All student teachers will choose one child in their own classes for a three-week case study. During this time, their regular student teaching journal will be devoted to case study field notes. Student teachers will also gather any additional data that are legally accessible to them by talking with colleagues and coaches and by observing the chosen student in out-of-class activities.

The teachers-to-be set out with their journals and our earnest teacher dozes off with a smile, imagining their discoveries—only to be awakened by a phone call from an anxious member of the group who was placed in a highly traditional, rural school district. Formerly a psychiatric nurse, the student teacher asks, “Don’t these case studies have to be confidential?” She is assured that pseudonyms are required in the final reports. “But we must need parents’ permission. What if we have damaging information in our field notes—doesn’t a doctor or somebody monitor what we write?” It seems that the student has alerted her cooperating teacher, who has spoken to the department chair and principal. Since the administration wants to protect family values above all, the earnest teacher educator is told that student teachers may not be welcome at this school in the future.

This crisis is not resolved until three deans intercede on behalf of the embattled teacher educator, who bandages her wounds and calls it a learning experience. The next semester, she drafts a detailed assignment sheet, makes copies for each school, and adds a cover letter asking principals to advise her of specific rules and restrictions in their district.

And now, Dear Reader, let us rest by the side of the road and reflect on the questions these two adventures have generated:

Do teachers have a right to look and listen intensely?

To write down what they observe?

To share what they write? (with a seminar? with the world?)

When does a teacher’s routine documentation become research?

Only the voice of the wind responds, with answers that are uninterpretable. But, magically, two maxims appear traced in the sand:

Action research is not medicine, psychology or therapy.

The “subject” is myself as well as my student.

Scene 3

Of course these two maxims cannot tell the whole story. Let us turn back toward the city to visit a team of urban teacher researchers, most of them African American, who are beginning to document their own practices in collaboration with the Writing Project.

The team leader and her administrator in the city public schools have called a meeting with the Writing Project director to discuss the plan. The director is not prepared for the challenge that awaits her. “What will you do with our data?” asks the administrator. “If my teachers do this research, will their names be on the report—or yours?” It seems the administrator is still rankling from a series of encounters with researchers from the university. “And one more question. How do you know that your treatment won’t have some damaging effects on our children, on children of color?”

Afterwards, the team leader admits that she herself has some doubts about the study. “I feel a little like Nurse Evers,” she says, referring to the Black woman hired by Alabama medical researchers to recruit indigent syphilis patients for an experimental “treatment”: no drugs, careful documentation, and slow death! The Writing Project director is speechless.

She wanders alone through crowded city streets, pondering these ever-more-puzzling misconstruals. At last she sees a pattern in the data. Stopping at a coffee shop, she scribbles on her napkin:

Action research is not an experiment with subjects, statistics, and treatments under the control of some outside scholar.

Action research must be owned and operated by teachers.

In this crisis, the Writing Project Director cannot turn for help to any deans in shining armor. Fortunately, the team leader continues to speak her own truth as a Black woman and as a teacher researcher. The team moves slowly, negotiating each issue every step of the way. But in three years these teachers have become leaders in the regional action research movement, and the city district is one of the strongest voices supporting the Writing Project.

Scene 4

The scene shifts to a suburban district known for elegant, tree-shaded estates and small but pleasant bungalows. There, an established action research team has been gathering data on their students “at risk,” including a disproportionate number of African American males. Teachers want to observe these students reading, writing, talking in their own classrooms, hoping to rethink their practice so that all their kids—Black and White, male and female—can succeed.

The action researchers, most of them White and female, huddle in the teachers’ lounge comforting one another after an ordeal at a major conference. An African American teacher had interrupted their presentation with “Why are you singling out our kids as your subjects?” Another member of the audience asked why the district didn’t just hire more Black teacher researchers.

“What they really meant,” mutters the team leader, “was how can a bunch of White broads hope to tackle Black male underachievement!” She looks around at her colleagues and laughs. “I finally said, ‘We know the kids need Black male role models, but unfortunately we’re all they have!”‘

She shakes her head, recognizing the irony. “When this project began, despite our good intentions, we’d talk about diagnosing and resolving the problems of minority writers without always questioning our own role in those problems. But that’s not where we’re coming from today.” The process of action research and exposure to work by African American educators have turned the team around.

“We tried to tell this guy about self reflection, about fixing our own underachievement,” laments her colleague, “but he just didn’t get it.” Team members finish the last of the microwave popcorn and scatter to join their families. Someone leaves a note pinned to the bulletin board:

If you’re not an insider, you just don’t get it.

Action research can help you get inside the experience of people from a different culture, class, or gender.

And then you just might get it.

This story, Dear Reader, is also one of gradual change rather than heroic action. In time, the White teachers gain a second sight, a cultural fluency if you will. In time, they could share their journey with African American teachers and usually get beyond the initial suspicion to real dialog. But now we must be on our way.

Scene 5

Trudging down a shady boulevard, we hear rumors that the Celestial City is near at hand. The scene is a small elite district where the dynamic new superintendent has just hired a consultant in qualitative research from the Writing Project. She will collaborate with a primary teacher to do an ethnographic evaluation of the teacher’s whole language program—the administrator wants some rich classroom portraits and case studies. The consultant is thrilled to have found a land where people understand and value action research.

For the next three months, she spends hours in the classroom and writes field notes documenting how children become literate in this environment. The teacher is an experienced action researcher. She has permission slips from all her students, a newsletter to communicate with parents, and several publications describing innovative work in her classroom. Each day the teacher and her research partner share their notes and insights. Finally, the consultant presents a sixty-page document including eight case studies (all with pseudonyms), samples of student writing, and scripts of classroom talk.

The superintendent is delighted—until she starts to picture the school board’s reaction to the document. The case studies and classroom portraits are indeed rich. In a class of twenty three, every child can be recognized! The superintendent places an emergency call to the consultant, who learns that she must now produce a ten page summary of her document, without reference to any particular child. “How can I write a case study without showing a real kid?” she wails. “Better to write a tale with no hero.” Calming down at last, she reflects and writes in her journal:

Gathering data in my own classroom to present to a public audience raises ethical issues quite different from other modes of teacher publication. When 1 as a teacher publish a short story, even one that draws on my own life or the lives of my students, l can transform the details in such a way that no individual will be recognized. When 1 publish an autobiography the risk of embarrassment is greater, but 1 am writing about my own life and the relationships at risk are my own. Even when an outside researcher studies my classroom, the report may disguise not only the teacher and children but also the school, district, and community to protect those who have been observed with the ethnographer’s eye.

On the other hand, when 1 as a third grade teacher in Podunk, USA, publish my own classroom research (whether alone or in collaboration), 1 will expose not only myself but also my children to public scrutiny. Once I identify myself and my school, l cannot fully disguise my students. And their behavior in our intimate classroom setting is exposed to the unpredictable response of adults who have not been personally admitted. (To visit my local public school, l must stop at the office, introduce myself, and get permission to sit in a teacher’s class; to read that teacher’s report in an action research journal, l need no such invitation.)

Rereading her own words she mutters, “OK, so now what do I do?”

The consultant eventually conquers her task with a literary sleight of hand. Retaining much of the rich descriptive text, she carefully avoids linking the identifying descriptions to specific children. Observe, Gentle Reader:

One group writes a play based on Flossie and the Fox. The book’s narration is in standard English, but most of the characters speak a rural Southern Black dialect. The five children who have chosen this project include two international students, one urban transfer student, one special education student, one first grader, one second grader, and three third graders. (Some fit more than one category.) Children recast each scene in the book as a script. They take turns writing dialog at the computer, print out a script for each actor, then practice as a group (coaching one another to get the right voice for each character, even the suave fox). Children differing in age, race, and culture write and perform enthusiastically.

Older, wiser, tired, and rather pleased with herself, the consultant bids farewell to the classroom of twenty-three children and returns home to cultivate her garden, saying, “There’s no place like home.” But first she grabs a marking pen from the plastic tub and makes a poster to display her learning:

Writing action research is not like writing ethnography, with anonymous informants and fictional settings.

Writing action research is a literary open house starring the kids in my own classroom.

And so my tale is told, my journey ended. But what wisdom have we gained from our five adventures? Can we generalize from such stories? Can we turn a picaresque tale into a code of ethics?

You remember, Dear Reader, the challenge set forth by the dean of research. He called for an alternative to the “human subjects review,” a document posing the ethical questions most relevant to action research. A few years ago, I did, in fact, take up this challenge as a member of the St. Louis Action Research Collaborative and ARC’s ad hoc committee on ethics. We hoped to compile a questionnaire that might be adopted for reviewing teachers’ research proposals in the master’s and doctoral programs of our local universities.

Our committee began with the human subject reviews currently in use, all of them implicitly designed for the traditional academic study. We examined ethics documents from four universities and three professional associations, only to find much of the same material. (“Humph! This won’t do,” I mused. “Yet perhaps, if Don Quixote can transform a kitchen maid into Dulcinea, I just might be able to transform these documents into something to guide an earnest action researcher!”)

After many drafts and several discussions in ARC’s teacher educators’ seminar, our impossible task began to emerge in a new guise. The more we had tried to set firm guidelines, to pin down the criteria for review, the more we had seen that ethical decisions were sensitive to context. Should a teacher’s field notes be shared with students? Administrators? The public? When must parents be involved in a teacher’s reflection on her practice? To place such decisions in the hands of academics who were not action researchers could create more problems than it would solve.

Abandoning the quest for an alternative “human subjects review,” we drafted A Guide to Ethical Issues and Action Research for teachers. Here are a few samples of the more-or-less provocative questions used in the guide:

Regarding the researcher’s purpose: What does your research aim to understand? What does your research aim to change?

Regarding the people traditionally viewed as subjects: Analyze the power relations. Which people (e.g. students, parents) do you have some power over? Which people (e.g. principals, professors) have some power over you?

Regarding informed consent: Which of the research participants at your school have read your proposal? Which ones have been informed of the research orally in some detail? Which ones know little or nothing about the problem? Explain and justify the decisions behind your answers.

Regarding cultural bias: Will your study attempt to read the experience of people who differ from you in race, class, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation? How have you prepared yourself to share the perspective of the “other”? Have you provided for consultation or triangulation by adult members of the community?

Most of these questions defy simple solutions. Many of the problematical ones don’t appear on any of the review documents we examined, but they are central to action research by and with classroom teachers. The Action Research Collaborative offers the Guide for teachers planning such projects to discuss with their research teams or thesis advisors. We hope that by mapping some of the road hazards before setting off on their journeys, teachers may less often blunder into legal, moral, and cultural quicksand.