Disrupting the Prolonged Silence: Youth Inquiry of the Tulsa Race Massacre

Curators notes:

The Oklahoma State University Writing Project partnered with the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation to disrupt the prolonged silence by empowering Oklahoma 6-12 grade teachers and students to answer the question, “What can we learn about the Tulsa Race Massacre to make the world a better place?”Summary:

Using digital tools and the power of student-inquiry, 6-12 graders explored the question, “What can we learn about the Tulsa Race Massacre to make the world a better place?” Here are field trip documents from when The Oklahoma State University Writing Project partnered with the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation in Tulsa to disrupt the prolonged silence surrounding the massacre.More and more public attention turns towards Tulsa as we approach the centennial anniversary of the 1921 Race Massacre. Television shows, such as HBO’s Watchmen, and the ill-timed June 2020 presidential campaign rally in the midst of a global pandemic and national protests against racism and police brutality thrust Tulsa’s history into public consciousness, but if you ask many lifelong Oklahomans about their understanding of that history, you would find many are learning about it for the first time. The Oklahoma State University Writing Project partnered with the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation to disrupt the prolonged silence by empowering Oklahoma 6-12 grade teachers and students to answer the question, “What can we learn about the Tulsa Race Massacre to make the world a better place?”

As we embarked on this project, middle and high school teachers from rural and urban communities across Oklahoma gathered for a weeklong boot camp workshop. We explored the history of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, discussed appropriate teaching approaches for traumatic history and student-driven inquiry, discussed texts to use with students and to improve our own understanding of the event, and walked the streets of Tulsa’s Greenwood District to experience the place where the massacre took place nearly a century before. Throughout our week together, we trained our teacher participants how to leverage four technological tools that aligned with the project types we wanted them to use to engage their students in their inquiry projects: Adobe Spark for digital storytelling, Anchor FM for podcasts, Google Tour Creator for Google expeditions, and YouTube Studio for TED-styled “LRNG Talks.” Because the teachers had differing access to technology at their schools, we identified tools that could be used on all of the devices that were available for them to use with students.

Central to the success of this project, each teacher participant facilitated a year-long inquiry into the Tulsa Race Massacre by planning and integrating a series of lessons into their English Language Arts curriculum. These lessons would culminate into student-driven inquiry projects that allowed students to take the lessons learned from the Race Massacre and create the change they wanted to see in their own communities, nation, and the world. Our teachers selected a variety of texts and themes to pair with the project, from Fahrenheit 451 (Bradbury, 1953) and the role of the media in instigating the violence during the Race Massacre to The Crucible (Miller, 1953) and how intolerance can destroy a society. They also used documentaries, such as The Tulsa Lynching of 1921 (Cinemax, 2000) and American Creed (Citizen Film, 2018), to further students’ understanding of race and racism and asked students to ponder the current state of race relations in the United States.

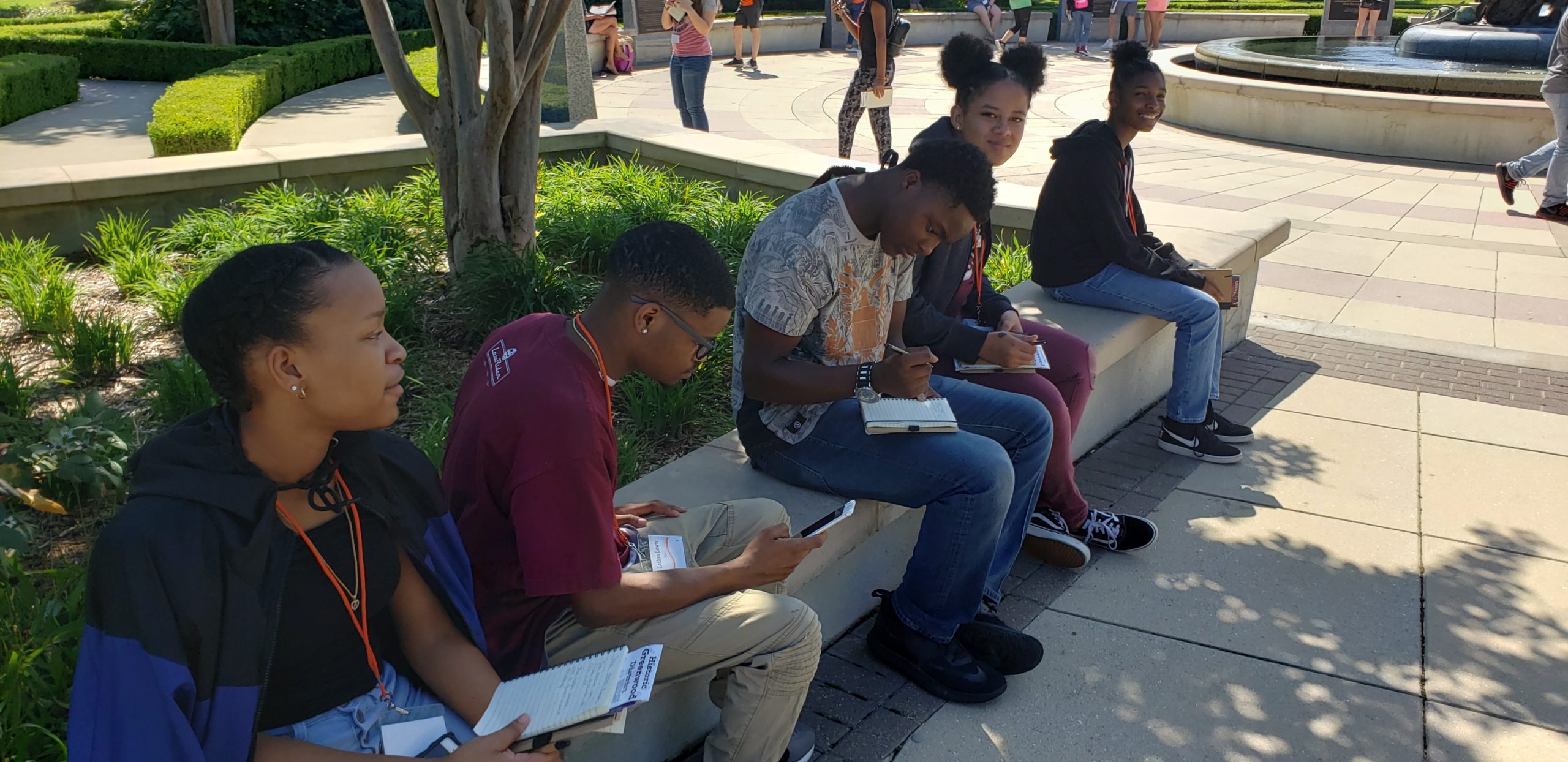

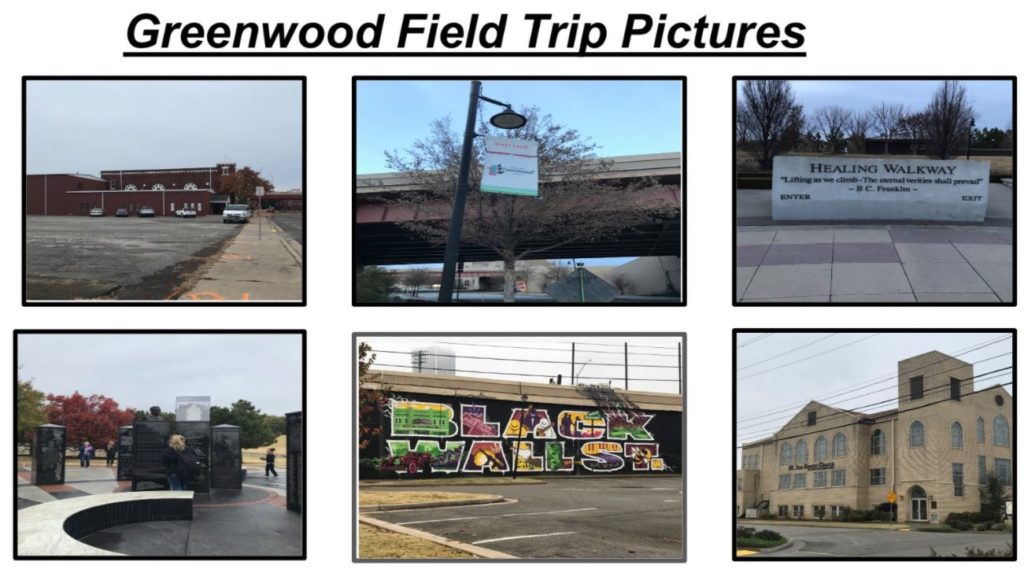

Along with the classroom curriculum, we also wanted the students in the project to see and experience the places they were learning about in their study of the Race Massacre. In a series of four field trips, we brought nearly 200 middle and high school students to the Greenwood District – the site of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. These all-day field trips began with students asking their burning questions about the event, such as: Why did this happen? How one group could hate another group so much that they would commit such an atrocity? and What did the African American community do to fight back? Many of these burning questions were answered throughout the field trip experience, as students read firsthand accounts at the Greenwood Cultural Center and learned about living in the 1920s at the Mabel Little House. We walked down Black Wall Street and discussed the prosperity and resiliency of the African American community before and after the Race Massacre. We pondered what the community lost and gained in the halls of the historic Vernon AME Church, one of a few structures to survive the destruction of that fateful night in 1921. Students had the chance to write and reflect on the legacy of the event on the Healing Walking in the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park. Each field trip ended with discussion and often more questions as students formed ideas for their own inquiry projects.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, we envisioned bringing these 200 students back to Greenwood to present their inquiry projects in a one-day youth symposium; however, plans changed as schools closed, and many students lacked the technology at home to finish their projects. Instead, we built a digital project repository to showcase our students’ work. Although not all our student participants were able to complete their inquiry projects, we gathered some amazing work from our students as they answered our question, “What can we learn about the Tulsa Race Massacre to make the world a better place?”

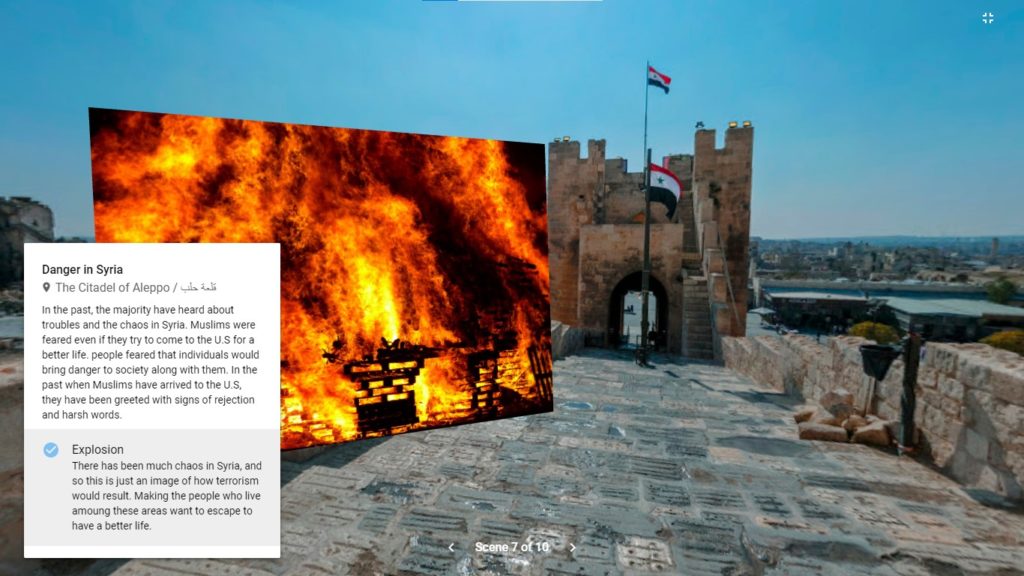

Using the four digital tools we described earlier, students produced digitals stories showcasing their 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre knowledge, podcasts on the intersection of race and over-policed communities, LRNG Talks on discrimination and stereotypes, and Google Expeditions mapping the effect of racism on communities around the world. Within these students’ work, we could see their vision for improving their own communities and creating a better world. Some students shared their dreams for a more just world, where all races, ethnicities, genders, and sexual orientations were accepted. Others questioned the economic and social barriers that prevent African Americans and other groups from equal access to healthcare. Two high school students shared personal stories around what it meant to be an immigrant and challenged lawmakers to take more just immigration reform. Another group took us on a journey from Aleppo, Syria, to their own Tulsa neighborhood in order to show us how discrimination scars communities. Using the Race Massacre as a starting point, the students’ inquiry revealed the lessons of this century-old tragedy extend beyond the borders of Oklahoma, or even the United States, and have the ability to transform the way we see the world.

As we pondered ways to move forward with this project, we wanted to give students across the country the opportunity to visit the Greenwood district in Tulsa and wander the streets, parks, and museums just as our students experienced on their field trips. We started designing digital field trips experiences using 360 cameras, Google Tour Creator, and other digital field trip tools (since Google Tour Creator is shutting down in June 2021). These should be added to our website soon. We also worked with our teacher team to create lesson plans on the Tulsa Race Massacre, digital tools, texts, and inquiries they used with their students. These lessons are in the process of being compiled into an open-access book, which will be available soon.

Through this project, we learned to let students’ questions drive our work. While we envisioned students asking hard questions about the history of the Tulsa Race Massacre, we could not see how these questions would have led to the answers students shared in their inquiry projects. The connections middle and high school students made between racism and modern day effects were jaw-dropping yet hopeful. We are also still learning. About how to position youth to ask the hard questions that drive their own learning. About how to offer opportunities for inquiry within curriculum development. About approaching topics previously invisible or hidden from the curriculum in our state. And about the deep schisms of racism and bias that still exist in our communities. Though 100 years in the past, the wounds are still very raw and very real.

Co-written by Shanedra Nowell, Kalianne Neumann, and Shelbie Witte, Oklahoma State University Writing Project