From Lines to Networks: Connecting with National Parks for Place-based Science Learning

On the Line

It’s a cold March day in New England. Fifth grade students, families, and teachers, shuffle into the Riverbend Farm Visitors Center in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, unbundling from their canal trail walk with Ranger Kevin. On the trail, they learned about the slow and uncomfortable pace of travel in the 1800’s and how canals were essential, for a time, in moving raw materials and goods to and from the early textile mills along the Blackstone River.

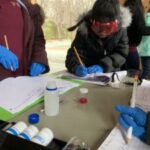

In this room, they will experience another harsh reality of life that accompanied American innovation– the brutal working conditions of adults and children laboring in America’s textile factories. The room is set with four assembly line workstations, each equipped with a stack of construction paper, one ruler, one letter stencil, two markers, an ink pad, and a “quality approval stamp.” Here, students role-play as mill workers in the fictional “Slater Stencil Company.”

Students are counted off in groups of five, and they take their places at each of the assembly lines– one cutter, one stenciler, two colorers, and one quality approver per station. Ranger Mark, who is role-playing the Slater shift manager, instructs students to produce high quality letter tiles using the materials provided in the most efficient way possible. As students get the hang of this piece work process, Ranger Mark bombards them with demands to work faster, work harder, and work better–– even while he fires workers off their lines and withholds wages (paid in company scrip) due to the company’s alleged financial troubles.

Park volunteers who have been lurking in the room with parents and teachers hand out fliers about labor organizing. They tell the workers that they don’t have to put their own needs behind those of the shift manager and the mill. They float ideas about better working conditions and better pay. They talk about solidarity with those workers who have been fired. They call for a work stoppage and enlist the remaining workers to form a picket line chanting, “Strike! Strike! Strike!”

Connecting With and In Our National Parks

Over the last year, the Science in the Park Grant, funded by the Ganz Cooney Foundation, supported partnerships between The National Park Service and The National Writing Project. Locally, park rangers from The Blackstone River Valley National Historic Park, faculty from The University of Rhode Island Harrington School of Communication and Media, and teachers from TIMES2 STEM Academy in Providence, RI partnered to design place-based science learning experiences for young people and their families.

The overarching goal of this partnership and the resulting programming was to cultivate the next-generation of Blackstone River stewards. This pilot program sought to raise youth awareness of the BRW’s historical, socio-cultural, ecological, recreational, and economic value as well as to prompt ethical, action-oriented approaches to conservation. To realize this goal, we designed a series of immersive science learning experiences for elementary school students to undertake with their teachers and parents in the BLRV park. These activities included walking and mapping existing mill villages, designing and building cardboard box mill villages, role-playing factory workers on an assembly line, testing the soil and water of the river to understand the environmental impact of industry, and using design thinking and simulations to generate solutions for removing environmental waste. These immersive experiences provided opportunities for young people, families, and teachers to connect science and technology to social and cultural concerns and to practice participatory, community-engaged science and science writing.

Schools, Factories, and Efficiency

The American Industrial Revolution was born in the Blackstone River Valley which spans from Worcester, Massachusetts to Providence, Rhode Island. Entrepreneurs like the Browns and Slaters bought land at key points along the Branch and Blackstone rivers to harness their extraordinary water power. They built both the textile mills and a series of all-encompassing villages for the workers who would labor in these mills. In the span of a decade, the nature of American life was radically altered as families moved into mill villages and learned the pace and time of assembly lines and shift work as opposed to the pace and time of the seasons and the harvest.

During this same time, the character of American schools was changing, too. Rigorous scientific management principles, born on the factory floors, were integrated into schools. Following the assembly line model, school administrators sought to break down the mammoth task of educating a rapidly diversifying public into smaller actions that could be performed by a differentiated school workforce. Students were divided into grade levels, and in the grade levels, students were further differentiated by academic achievement. Each task or action could be measured, analyzed, and studied to find the most productive means to reach a desired end, and, ultimately, schools and teachers were measured by their ability to efficiently produce capable workers for the industrial marketplace.

“School is a factory. The child is the raw material. The finished product is the child who graduates. We have not yet learned how to manufacture this product economically. No industrial corporation could succeed if managed according to the wasteful methods which prevail in the ordinary school system.” –E.F. Shapleigh, 1917

Over a century after Shapleigh advocated for a factory approach to education, we are still dealing with this legacy of industrialization in educational programming. This is true in both formal and informal learning contexts. Schools continue to place unwarranted value on standardized testing and incrementalist “growth.” Similarly, informal learning institutions such as museums and parks all too often take a one-size-fits-all approach to educational programming. You know the drill–students watch the video, take the tour, eat their lunches, and exit through the gift shop. These visits focus on historical or cultural content delivery as opposed to designing participatory learning opportunities that focus on learner interests, authentic inquiry, and place-based connections with nature, history, culture, and others in their communities.

Connecting Learning

The national conversation about education, however, is shifting. The public is less concerned with “ achievement” as defined by standard test scores and more interested in questions of equity, engagement, relevance, and schools as spaces to imagine more democratic futures. We are no longer training students to do piece work on factory floors; instead, we are cultivating creative problem-solvers who can generate their own ideas, communicate and collaborate with others, and adapt to rapidly changing workplace, home, and civic contexts.

As purposes change, so should practices. To think about how we design responsive learning contexts that build individual and community capacity, we can turn to the Connected Learning framework. Connected Learning is a research-based agenda that helps educators in formal and informal contexts to reimagine learning in a participatory culture. Based on learning principles that privilege student interest and passion and peer networks for academic, economic, and social achievement, Connected Educators design experiences that are:

Openly networked, where responsibility for learning is claimed by people and institutions beyond formal schools;

Production-centered, positioning learners as makers, not just consumers;

Designed to foster shared purposes, including opportunities for intergenerational making and learning

The Ganz Cooney Foundation spark grant provided us a unique opportunity to connect our National Parks as key partners in science and technology learning. What’s more, it provided the National Parks an extended opportunity to work with teachers and university faculty to design and test innovative science literacy programming. At BLRV and other sites, this work expanded the programming repertoire as National Parks have traditionally focused on historical and cultural education and interpretation. And while building these inter-organizational partnerships is never easy or efficient, they are essential in designing transformative learning experiences that thread through young people’s in and out-of-school learning.

Early in our partnership building, we spent time mapping our assets across organizations. For example, we identified physical spaces across the BLRV park nodes which were conducive to organized outdoor learning; identified rangers who had particular expertise with the history of innovation, with the mechanics of the water wheel, with soil and water testing kits, etc.; leaned on Americorp Vistas like Tammy Boyd (without whom this project would not have been possible) who had extensive experience with science curricula development and project planning; and tapped particular park volunteers who might be interested in facilitating different activities. The elementary school teachers identified curricular priorities, learning challenges, particularly in their engineering curriculum, as well as timing opportunities. They chose to focus on fifth graders who were participating in standardized science testing and scheduled field trips around testing sessions so that students would experience science as something more than a set of multiple choice questions. University faculty capitalized on their expertise in science and technical writing as well as experience in designing Connected Learning environments to promote open-ended inquiry and engagement. Students were presented a menu of options for the kinds of experiences we could offer in the park, and they, too, identified their interests and priorities, helping us to develop a responsive programming plan.

In this work, we recognized young people and families as active knowledge makers– using the tools, technologies, and thinking practices of community-engaged scientists. We designed provocative programming like the toxic rice challenge and assembly line simulation to activate emotion as a key component of transformational learning. And it was clear from student and parent responses that we struck an emotional chord. Students wrote passionate persuasive letters to Ranger Mark arguing for the changes they needed at the Slater Stencil Company, and each time the bus pulled into the park and Ranger Mark came out to greet us, they pointed and exclaimed,

“Hey, mistah! You’re the one that fired me!”

Parents and teachers who joined Uxbridge trip also shared their reactions to the assembly line simulation, noting the currency and relevance of this experience. Labor disputes among unionized teachers, non-union school leadership, and the city were taking center stage at that time, and students were struggling to understand these tensions. During this time, parents, teachers, community members, and administrators engaged on a weekly basis in open discussions and debates about working conditions and the future of the school. Somewhat serendipitously, the assembly line programming provided a historical lens for understanding labor organizing and the difficult but necessary negotiations among stakeholders.

Connections and Missed Connections

One of the most challenging aspects of this partnership was bringing parents and families into full participation in the park. In this high needs urban school setting, families found it difficult to take time off to attend events and we failed to understand that effectively communicating with families means more than finding the appropriate media such as Facebook pages, emails, texts, or fliers sent home with students. It also means attending to language diversity and making communications, invitations, and programming information accessible to families whose primary language is not English.

Despite these barriers to access, families did attend and participate in the Science in the Park programming. We were excited to see parents taking leadership roles in facilitating activities, especially the toxic rice challenge that prompted students to consider the delicate nature of removing toxins like heavy metals from the Blackstone riverbed. In this activity, student groups were matched with adult partners– either parents, park rangers, or teachers– and challenged to remove a bucket of rice from a “toxic zone” using only ropes and therapeutic stretchy bands. Participants were challenged to keep all body parts out of the 5’ “toxic zone” radius and used design thinking prompts to figure out how to collaborate with their team using only the materials provided. This activity proved quite a challenge for classroom teachers and students; however, several parents were quick to think of design solutions, and despite language barriers, shared their engineering prowess through hands-on instruction and technical illustration. For us, this underscores the importance of designing activities that incorporate direct practical experience as well as multiple modes of meaning-making and communicating knowledge for diverse audiences.

From Lines to Networks

As our program year draws to a close and we reflect on our work in this grant cycle, we are considering the value of thinking beyond linear models for learning in our institutions. Assembly-line thinking served its purpose in 19th century factories and schools; today, however, it serves us better to think about education as a series of networked experiences. Networks criss-cross time and space to bridge school, home, and community contexts as well as indoor and outdoor classrooms. Networks enable us to travel together on sideways paths that cut across content areas and disciplines as well as to imagine learning opportunities that cross generational, cultural, and institutional divides. These networks cannot be produced on an assembly line. They can only come about by connecting our interests, curiosities, dreams, and desires which are always already linked to places and the people who inhabit them. This is the crux of connected teaching and learning, and it has been a pleasure to practice it with others in our National Parks.

“National parks are the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.”–Wallace Stegner, 1983