Lights, Camera, Social Action!

Curators notes:

Participation might mean having a voice online, or in a neighborhood. Texas teacher Katie McKay describes how her highly diverse fourth grade students represented their exploration and understanding of discrimination through the creation of their own writing, comics, and films that they shared with other students both in their school and in their community at a local bookstore known for hosting speakers with strong political voice. McKay describes the students' work in a digital medium as having a voice and power that could not have been established through other means. After a showing to fellow students, the impact was obvious, she wrote: "...we felt that we had appealed to the masses. We believed that each student in our audience was walking home with a better idea of the power our words, actions, and gestures have to divide or to unite." On September 9, 2010Summary:

Kate McKay shares student work from her fourth grade class as they complete a unit on discrimination and describes how the students’performance of the work completely unended the audience's biased expectations of their school. Shown here are examples of student storyboarding as well as links to inspirational texts. Originally published on September 9, 2010“She doesn’t even speak English.”

“I guess we’ll let the white kid play today.”

“I better give this broom to a girl. Sweeping is a woman’s job.”

“Do I have to be in a group with him?”

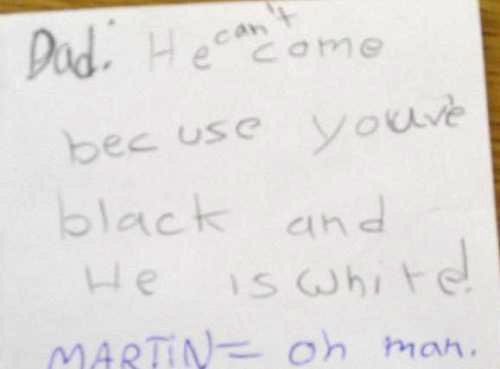

Whether my fourth grade students’ comments were said with a giggle and a nudge or a roll of the eyes, I heard them. I saw them. We all felt them. I guess I could have responded with a “Let’s not be cliquey, boys and girls,” or a teacherly, “Now, now. Let’s be nice.” We could have continued to avoid the awkward, but we chose to confront the parasitic -isms that were draining the life out of our shared space.

I had originally applied to teach at the school, in part, due to the student demographics. We’re a small Title I school of under 200 students. While our student population is primarily Latino, African Americans make up 16%, and we also serve a few white and Native American students. Based on my four years’ experience in Texas, I’d say we’re a pretty diverse group. This particular year, my class of fifteen included students who were mixed racially, who had come to us as refugees from Africa, and who were from upper-middle income white families. I had a student who was closely tied to his Native American culture and others who were first-, second-, or third-generation Mexican Americans.

The diversity that I loved brought with it a dynamic for which most students are not equipped with politically correct phrases or stock niceties. At times, the prejudiced words and gestures that thrive outside a school’s walls seeped into our learning environment and leaked out of the lips of students. As if such words weren’t degrading enough, our school had been, for the first time in its 70 years, branded with the scarlet letters “AU”: Academically Unacceptable. I begged for a few minutes a day to address the social climate that was infringing upon our learning environment. But, my schedule was not my own. “There is no time to waste,” I was told.

No Reading or Writing to Waste

As a nation, we were on the verge of electing our first African American president. Surely I could weave themes of acceptance and celebrations of diversity into the curriculum. I had to turn “no time to waste” into no reading text or writing topic to waste. Our studies of text features or summarization would happen around texts that gave justice to discussions of struggles for equality and change. Days of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Presidential Inauguration would come just as our unit on discrimination in the history and present of the United States would begin to scream for action.

Now that I reflect, I can hear a theme of screams that was threaded throughout this undertaking. We heard squeals of laughter when we first began to use the word ‘sexism’ to describe the scenario that Melanie later portrayed in an iMovie. We learned to shush shouts and actions of racism, without calling the culprit, as a whole person, a racist. As we delved deeper into uncomfortable topics that have plagued our past, and continue to eat away at freedom in our nation, it became okay to interject, “That has happened to me!” or even (more quietly), “I am guilty, too.”

While “white only” signs and segregation were easy for us to point a finger at in hindsight, we needed to take a closer look at some of the more subtle micro-aggressions that are not as simply identified today. Through in-depth study, we could see how these acts of discrimination are intricately woven into our society. How could we share knowledge of some of the roots of today’s problems and also call an audience to action to help us to move into a more equal future? Could we motivate the masses, as had the leaders of yesterday and today?

Our Presentation

In deciding upon a format for presentation, we reflected on our strengths as authors and our interests as readers. We had worked on sequencing, on using dialogue effectively, and on creating storyboards to plan. At first we thought we would write scripts and act them out on video. But when it came time to cast parts we had to ask, Does a female or a black student have to play the victim?

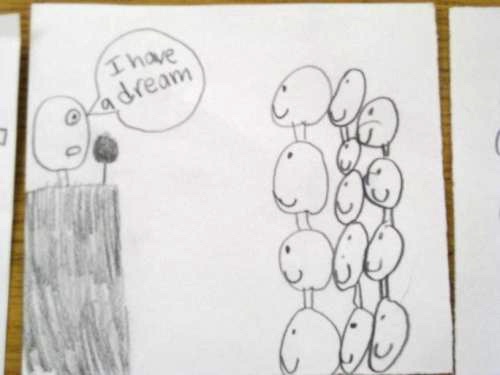

Unsurprisingly, Jeff Kinney had influenced my students as readers, drawing them to the simple lines of characters with complex personalities and dilemmas. Just about every member of our class was, at the time, obsessed with sketching Kinney-like comics. Could we draw the movie like a comic? Some asked, What if I’m not a good cartoonist? But we all knew that our words would be what truly held our meaningful messages. Choosing the technology for presentation would be tricky. We wanted to reach a wide audience and to hold their attention at a level that could educate and motivate change. How could we get our cartoons onto a screen? How could we make our voices not merely heard, but truly listened to?

I had experimented enough with the iMovie application on our classroom computers to know that I wouldn’t have to spend much time training students to get them started. Knowing that we could insert images and that my students had already become accustomed to being ‘photographers’ with my digital camera, we realized that we could take a digital picture of each cartoon slide. We could imagine our audience’s engagement with our class-written, class-produced movies.

Fittingly, we formed heterogeneous groups. Both our process and our purpose created the inclusive community that a simple “Let’s all be nice” would have made impossible. When it came time to record students’ voices, we listened to the sound clips over and over, and the term “voice,” that students recognized from rote rubrics, materialized. With the combination of original drawings and recordings, the pieces gained a personal dimension that another medium could not have accomplished.

Questions and Obstacles

As is the beauty of group projects, certain questions and obstacles arose.

“Our group’s not big enough for all of our parts. Could someone from another group make a cameo appearance?”

“We need someone who speaks Spanish. Could someone help us?”

The answer to each problem was to include someone who had been excluded or to step into the shoes of a character different from oneself. A Mexican American recorded the words, “I have a dream….” A boy read the part of Rosa Parks refusing to stand. So, while each movie advertises two to three writer/producers, there was much overlap as we scripted, cast, and edited.

On the Friday before the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday, we set up the projector and had a full schedule of third through fifth graders signed up to view films. First, we shared the work that summarized what we had learned about the history of discrimination in our nation. We closed with video that included youthful voices of action and commitment to change. As we left school for the three-day weekend that now held new meaning, we felt that we had appealed to the masses. We believed that each student in our audience was walking home with a better idea of the power our words, actions, and gestures have to divide or to unite.

At the End of the School Year

At the end of the school year, the fourth graders who participated in this discrimination unit celebrated the writing they had done throughout the year with a Young Authors Reading. At our school, we are fortunate to be centrally located near many local businesses. One such business, La Resistencia Bookstore (so named due to the organization’s history of resistance), has “sponsored/endorsed readings and political forums that included nationally and internationally known writers, human rights activists, and indigenous artists.” La Resistencia welcomed us into their space to share a variety of pieces of our work. Students were given the option to choose from any piece they had worked on throughout the year. Many students chose to share their anti-discrimination movies. Several teachers, parents, mentors, local authors, and university professors also accepted our invitations and attended the event.

At the end of the reading, we welcomed feedback and comments. One professor pointed out to a proud group of fourth graders that the work we were doing in our classroom was the type of work that many university professors were talking about. Another audience member leaned over to ask a teacher of our then “Academically Unacceptable” school, “What kind of school is this? Is it a magnet school of some kind?”

None of the district supervisors who had spent so many hours in the classrooms of our school throughout the year showed up at the reading that day. However, we remembered their words. Only now their words, like Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, hold new meaning. “There is no time to waste.”