Summary:

If you are developing or facilitating a professional development program that includes peer editing as a topic/theme/strand you will want to check out Denise Marchionda's "two-peer editing system." Marchionda shares the checklist and specific step-by-step directions she has students follow in her class when editing/reviewing one another's writing. She also shares specific examples of how the strategy led to improved student writing. The article would be useful as a stand alone discussion piece in a professional development session, but even better if it were read, discussed and followed up with teachers engaging in the process with their own pieces of writing, enacting the NWP core belief that teachers of writing should also be writers themselves.“Would you ever consider murdering a loved one?” became Ruth’s attention-getting lead for her essay on assisted suicide. From there she went on to cite several emotionally driven cases in which assisted suicide had been used to end suffering. Her writing strategy was developed in response to having two peer editors review her first draft and make specific suggestions for improvement. Her first reviewer, Ollie, remarked, “You need a better hook”; her second reviewer, Katie, suggested she cite others’ experiences. Both reviewers helped Ruth see that what she wrote did not convey what she wanted her reader to understand. Ruth’s original opening line on her first draft had read, “There is one state where assisted suicide is legal,” and she then went on to explain why it was legal there. Because Ruth had two reviewers’ comments with which to work, her final essay was much more appealing than her first draft.

The above exchange was one of many written conversations I witnessed when employing my Two-Peer Editing Strategy in my college composition class at the New Hampshire Community Technical College, in Nashua, New Hampshire. Using the two-peer editing system, students were challenged and prodded by differing points of view, which led them to improve their writing and revise to better reach a wide audience. For me, the Two-Peer Editing Strategy has advantages over the alternatives: a teacher-only reading, single-peer editing, and group-response editing.

Using the social aspect of writing, two-peer editing encourages a helpful and nonthreatening atmosphere in which students are free to talk about their writing. After learning the process, students are able to discuss what led them to write about a certain subject, why they chose a certain organizational pattern or word, and what they can do to fix-up their manuscripts. This frees up the student writers to experiment with new ideas, words, and patterns. They become aware of writing as a social construct and realize that their writing affects individual readers differently.

Consider the case of Amy, a well-trained academic writer, who had a hard time making her direct writing style interest her readers. Classmate Ethan, having done the first review, stated that her title, “Cheerleading: Sport or Activity?” was “DULL.” (Yes, he wrote it in capital letters.) He then made a few perfunctory comments and corrections throughout the essay. Tara, the second reviewer, offered that she liked “the use of factual research,” but suggested Amy “provide [more personal] reasons for [cheerleading to be considered] a sport.” Tara wanted Amy to add emotion. She specifically suggested adding “My teeth would clench” after “the boys on the football team and others were always telling us what we do is not a sport.”

Tara was very sensitive in her critique, but some students, like Ethan, were a bit blunter with their comments. After the first exchanges, however, students began to take criticism in stride and found that if they did use other students’ suggestions, their writing often would become much better.

Amy’s final draft was entitled “Ladies Flying High,” and it included many memories of her struggle to make others believe in cheerleading as a sport. She used input from both reviewers, and her essay benefited from having the two rather different points of view. If she had had just the one view—Ethan’s for example—she may have jazzed up the title and done little else.

While I knew that I could not expect my students to do a professional-level edit of each other’s essays, I was reasonably assured that between two reviewers, each essay would get a closer examination than with just one set of eyes. I also wanted to give my students a positive attitude about revision; I did not want them to have a “limited sense of revision,” as students are often “very forgiving of papers having underdeveloped ideas and claims” (Beason, 1993, 395). Most students do not think that their peers have the skills to be able to edit each other’s essays (Helfers, et. al., 1999). Using the two-peer editing system, however, increased the likelihood that each paper would receive a quality response from at least one editor.

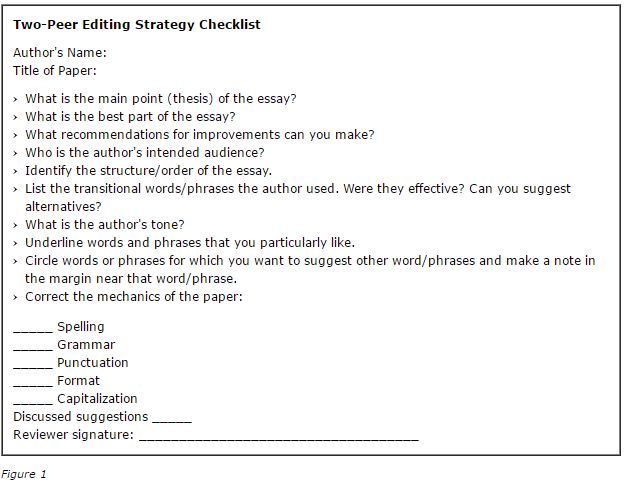

I developed a checklist that I hoped would elicit greater discussion between the writer and dual reviewers. I wanted the reviewers to offer “insights and additional perspectives, which can lead to a better understanding and, ultimately, a greater sense of ownership for the writer,” (Hodgson and Bohning, 1997, 139). The social interaction encouraged by the checklist would also need to allow the free exchange of ideas and suggestions without the sense of only one right way of expressing one’s self. Throughout the writing process, I emphasized the recursive nature of writing and the fact that nothing written is ever final. I wanted my students to consider many ways of constructing meaning through their writing. (See the Two-Peer Editing Strategy Checklist, figure 1.)

After developing the checklist, I then had to consider the process that would emphasize the social construct of writing. I wanted my students’ writing to have an audience of at least two peer reviewers and myself. This is what I had them do:

- The students came to class prepared with two typed copies of what my class began to call their “first final draft.” Two complete copies were needed because two separate students reviewed each draft, and each student needed a clean copy to review so as not to be influenced by each other’s comments.

- Peer-review partners were randomly selected. I shuffled index cards with students’ names on them and had each student draw a card to determine his or her partner. By using this pairing technique, students ended up working with different partners almost every time.

- Partners took turns reading their work aloud to each other. The partner reading aloud made corrections to his or her essay while reading aloud.

- Students then edited each other’s drafts using the Two-Peer Editing Checklist.

- Partners took turns discussing and explaining their editing suggestions.

- Reviewers signed the bottom of the checklist. This emphasized the importance of the editing phase—for which reviewers received a grade—and also reminded the author of who to ask for clarification of an editing suggestion.

- Students then drew the name of a new partner from the pile of index cards. They exchanged a second clean copy of their essay with their new partner. The new partner actively reviewed the essay using the checklist.

- The second set of partners took turns discussing and explaining their editing suggestions.

- The second reviewer signed the bottom of checklist.

- Students took both checklists and the reviewed copies of their own essays with them to revise the final copy.

Although going through the peer review process twice was time consuming, it was time well spent. Having two peer editors also offered each student the chance for a quality review, even if one partner might be “less able.” As well, students could compare reviewers’ responses and decide whose advice would be the best to follow. For example, if both reviewers pointed out the same errors or suggested a different way to approach a topic, the student could be reasonably assured that they needed to heed the advice.

Some students became sophisticated in their reviewing and, toward the end of the semester, began to delve deeper into others’ writings. Candice, a struggling writer, was defending her right to choose abortion when she wrote, “I would disagree with using the word murder because it is for a good reason, which is to save the mother.” In his review of her paper, Donald replied that this “is very subjective; [you] need source to back up.” In response Candice added Roe vs. Wade and Doe vs. Bolton as sources and changed her conclusion: “These cases received the decision of health officials who evaluated the status of danger…to a woman’s life.”

Other reviewers concentrated on mechanics, spelling, and grammar. Reta, Candice’s second reviewer, went through the essay with a fine-tipped pen. She changed phrases and verb tenses, noted spelling errors, and added punctuation that made the essay much easier to read.

Candice had just the right two editors for her essay. She needed both the content developed as well as the mechanics corrected. By using the Two-Peer Editing Strategy, Candice got the help she needed. Her essay became much better for it; in fact, this was to be her best essay for the semester.

When I first introduced my Two-Peer Editing Strategy to the class, some students were hesitant to comply. For some students, as Hansman and Wilson found, “asking a peer in the classroom to critique their writing was something unfamiliar…,” but after doing it for some time “it was a natural step that they added to their processes of writing” (1998, 22). Once students found that the process was helpful to them, they readily took part. If I had tried to use the traditional response group, (readers review the material in advance of the meeting, the writer reads aloud to the group and perhaps asks the group what she wants to know about her piece, and then responders take turns critiquing the work as others listen), students would have been intimidated by a group critique and certainly would not have had the skills necessary for effective review. Using one-on-one partnerships allowed students to become familiar with the process of critiquing. Redoubling their review efforts widened their critiquing skills and allowed for an expanded audience for their ideas and essays.

Researchers and practitioners agree that peer response helps writers improve their essays (Goldberg, et al., 1996). Getting more than one peer to review their work appears to make students’ writing even better. When students get genuine reactions and specific suggestions from two points of view, they can revise their work to satisfy a wider audience.

One student commenting on the process said she learned that writing “is never really finished” and that it is “more than sitting down and typing…it is being able to explore your mind.” The Two-Peer Editing Strategy has convinced me that, in these circumstances, three minds are better than one.