(Re)Defining Youth Space: Adolescents “Reading” a Place

Curators notes:

In recognizing the complexities and tensions around youth spaces, a team of Clevelanders came together in the Spring of 2019 to design a collaborative inquiry into place. Given the emphasis on understanding how young people understand spaces around the city and what spaces were (or were not) for them, adolescents are critical partners in this community-focused, place-based work called “The City is Our Campus.” On April 9, 2020“Creative placemaking can help turn boundaries (edges where things end) into borders (edges of interaction.)”

Trekson, 2018

It is commonly understood that adolescents are actively navigating the dynamic process of identity development. During this time, young people are closely attuned to determining where they feel a sense of belonging and where they may feel excluded. Youth, like most people, want to spend time in spaces that support their needs for socialization and expression, but also feel inviting and supportive. Young people are constantly making decisions about where they will spend their time based on the places that feel welcoming, whether real or imagined. In most urban contexts, the large numbers of parks, museums, and libraries, as well as a public transportation system, should mean that there are many different spaces and places available to/for young people. Yet, many young people do not feel that many of the city’s museums and other places are “for” them.

We know that space and place are shaped by a number of factors including but not limited to economic, cultural, political, and accessibility (real or perceived). Place, as we often see in schools and churches and local neighborhood parks, has a unique capacity to bring people together, yet it can just as easily divide individuals and communities. An ongoing challenge to improving civic engagement, community participation, and a sense of belonging for residences in nearly any city or neighborhood is tied closely to the characteristics of the physical environment as well as the habitual practices, cultures, and routines that are associated with a given space. We have found that many businesses, libraries, and art museums often reflect existing social tensions that lead to perceived barriers for young people and discourage them from seeing these spaces as their own.

In recognizing the complexities and tensions around youth spaces, a team of Clevelanders came together in the Spring of 2019 to design a collaborative inquiry into place. Given the emphasis on understanding how young people understand spaces around the city and what spaces were (or were not) for them, adolescents are critical partners in this community-focused, place-based work of our 2019-2020 LRNG Innovator’s Challenge grant project, “The City is Our Campus.” The City is Our Campus was developed around the concept of creative placemaking. Creative placemaking is a process that entails thoughtful programming, ongoing collaboration from multiple stakeholders, and community commitment. Our collaborative work began in the classroom by introducing students to some of the skills necessary to “read a place.” For every place students visited, students would consider: Whose space is this? Why do you think that? Students would have to analyze the characteristics of a space and what prior assumptions they had about certain spaces. Students would use this skill to read various spaces in the community through a series of “neighborhood visits.” Students would experience the community spaces with the professionals who are familiar with and work in the given space every day. The project’s community partners would support the students in their process of “reading a place.” To prepare for the on-site experiences, students conducted preliminary research into every site so they had some familiarity with the sites they would visit in person.

This post offers a glimpse into the place-based “reading” experience at the Cleveland Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA). This experience at MOCA was one of several neighborhood visits and reading experiences during the year-long project. Prior to the trip, a small group of students researched and presented what they learned about MOCA before to the class. Another critical step before the visit was a conversation between partners at MOCA and the project coordinators. This conversation focused on what the trip would look like in an effort to ensure that the visit would focus on engaging students in “reading a place.” It was agreed that the visit would be interactive and allow students to facilitate their experience in how they read the space. The students’ classroom teacher and project team member developed a handout that helped guide students in the process. The guide included a series of questions specific to art and this particular art museum.

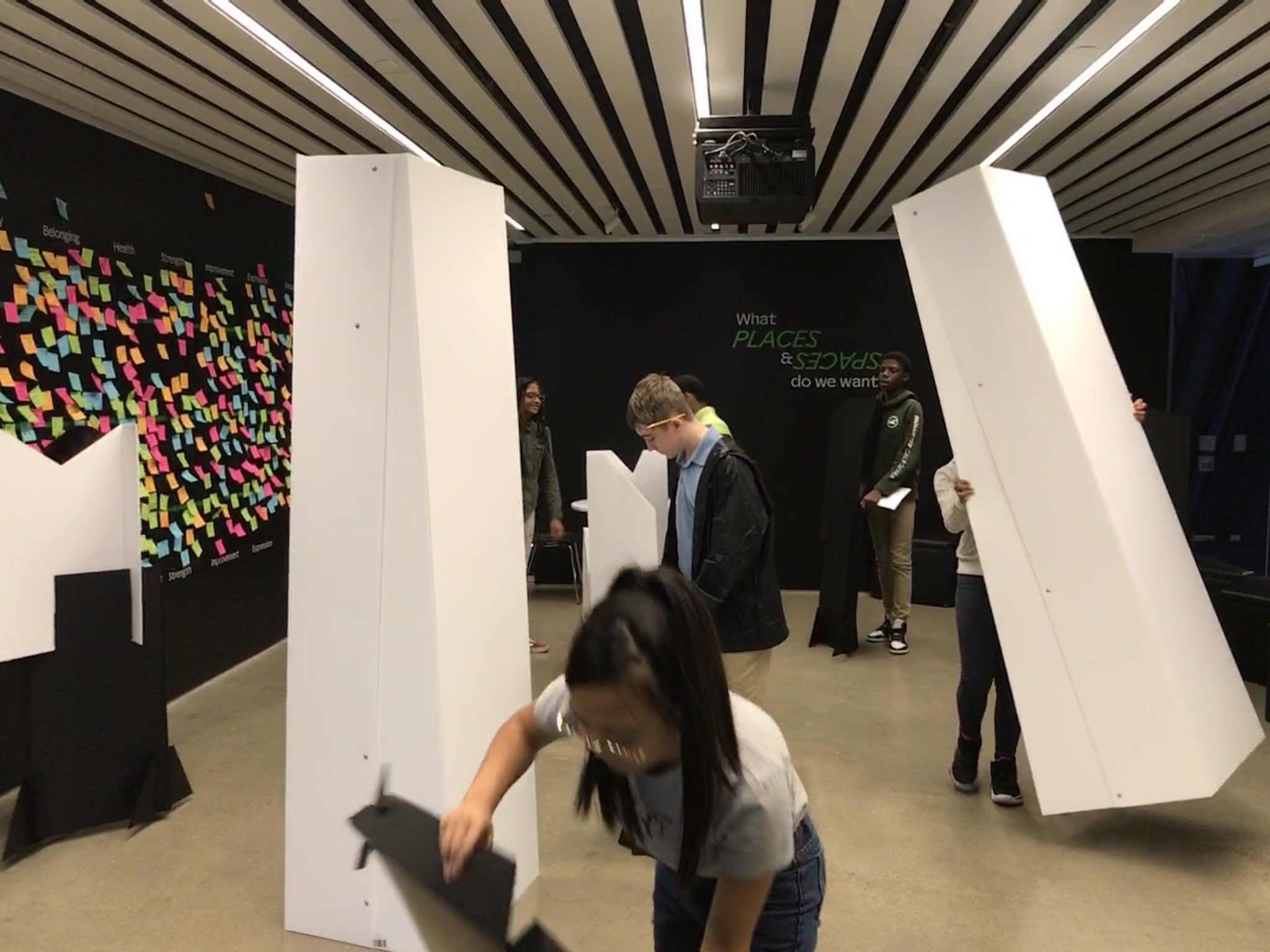

Active participation was encouraged and fostered as students were prepared with questions to ask and answer, and a clear place to collect their ideas. As a result of the pre-visit planning, the partners at MOCA led students on a well-designed tour of several exhibits in the museum. The experience was incredibly thoughtful and personalized. During the visit, we noticed students reflecting on their prior assumptions of art museums and MOCA as they “read” different spaces outside and inside of MOCA. At different points during this visit, students were engaged in interactive time in a kind of embodied way that was designed to give students a glimpse into what makes a contemporary art museum, and this contemporary art museum, distinct from other art museums. For example, at one point students were asked to try to assume a role or object or other element of a large piece of work that covered one entire wall of a room. Students made their choices and assumed some position reflected what they saw in the artwork. To expand the experience, our guide asked us to enact the scene(captured in the opening image above.) At this point, we all started acting out the position we assumed and bringing to life the various ways all of us interpreted the piece. A second interactive and embodied experience unfolded when students were assembled in a mid-size room with a collection of differently sized cardboard structures. Operating in silence, students were charged with moving the structures around the room, as they saw fit and on their own time. In and through this experience, students witnessed how physical changes to the space altered their experience of the space and changed how they could operate and move in the space. The experience was a very visual and physical representation of how we might feel welcome in certain spaces but how small moves or changes can quickly change a sense of welcome or openness and instead suggest boundaries, borders, and walls. The image below is a snapshot of this interaction.

What Places and Spaces do we want?

The visit to MOCA offered a series of immediate and powerful invitations for students to interact with and “read” a place. The embodied nature of this visit was important for all of the students in their ongoing efforts to think about space and place. Here are some of the specific conversations that were elicited during this visit:

- Students talked about art as a way for people to express their ideas, opinions, emotions, and experiences.

- Students expressed ideas about museums as a place to gain access to new ways of expressing ideas. This included discussion of art as a place to see and experience ideas in ways that might never occur to us as well as comments about gaining new ideas about the possibility to experience the arts with our bodies and ears, and not simply, as is commonly thought, our eyes.

- Students talked about art as advocacy and social justice work. This was tied to their experience of and response to “Birdcalls,” a provocative exhibit by Louise

- Lawler that uses sound and noise as a way to address the skewed gender dynamics of the art world, with particular attention to the role that name recognition plays in establishing oneself as an artist

- Students talked about big questions about the role and value of art. Why does it matter? For whom? One small group of students who would focus on art as part of their year-long inquiry would continue to consider these questions as they built an inquiry into the spaces and places in which we encounter art.

A central aim of this project is for the youth to engage in place-based efforts to try to shift how young people use or inhabit different places around the city. We designed the project in collaboration with stakeholders from different city spaces in hopes that young people could think about how they use or could use, city spaces with other community members. As emphasized in the project title, we hope to make the city of Cleveland a living, learning lab for students enrolled in one of Cleveland’s public schools. Drawing on the creative placemaking tradition, our team designed this project with the belief that young people’s place-based efforts could create innovative ways to connect residents with more places and more people across the city.