The Dilemma of Copyright and Digital Texts

“Mr. Conroy, can you come over here a minute?” asked one of my sixth grade Language Arts students. “I can’t seem to save the image from this website to put into my digital story.” The student pointed to a picture of Kinga Ka, the tallest roller coaster in Six Flags Great Adventure, on the computer monitor.

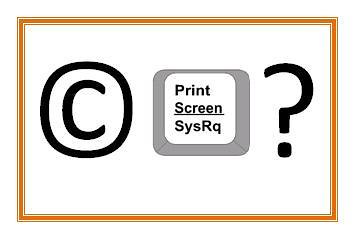

I grabbed control of the mouse and attempted to right click “Save As,” only to learn that the image in question was embedded with Adobe Flash and could not be cut and pasted the usual way. Without any second considerations, I demonstrated a workaround: I used the Print Screen button to capture a screen shot, and then I edited the image through the Paint program included with Microsoft Windows. We then saved and inserted the edited image into the digital story my student was composing in Movie Maker. We outright ignored the extensive copyright notices written in fine print down in the footer of the website.

Without any comprehensive awareness of the legally reusable media already available on the Internet, I had resorted to a two-pronged approach of lifting copyrighted images directly from websites and blindly utilizing Google Images. Some time later, our district’s technology administrator blocked access to Google Images, severely limiting my options. I was running out of resources for digital media (as far as I was aware). I was desperate to find images, no matter the cost. At that time, I reasoned the educational ends justified the means, even if I was potentially breaking federal copyright law.

Perhaps my frustration was to blame? That’s an easy scapegoat. No. Rather it was misunderstanding, or rather, a lack of any understanding of how to navigate copyright law as my students and I acquired and used digital media. It had never crossed my mind that my workaround might have violated federal copyright laws. I was of the mindset that if digital media—images, video, audio—were openly viewable on the Internet, then they were free for the taking. Of course, this is far from the truth of the matter; the guidelines for re-purposing digital media in an educational setting are much more nuanced than my previously held assumptions.

Over the years, I’ve developed a better understanding of where my students can access copyleft friendly media, and how we can properly use copyrighted materials and respect intellectual property through fair use practices. In the next few pages, accessible through the <page links> below, I share some of what I learned.

Creative Commons and Copyleft

To be perfectly honest, my preconceived notions about copyright were misinformed and incomplete at best. In my mind, the familiar WARNING: For private use only. Federal law provides severe civil and criminal penalties for the unauthorized reproduction, distribution or exhibition of copyrighted motion pictures and video formats that precedes movies applied to all copyrighted works. This belief was reinforced by the media’s coverage of the Napster trial and other forms of digital piracy.

The two extremes of over-compliance and outright disregard for federal law appeared irreconcilable, and navigating between them only complicated my classroom practices. On one hand, I gravely frown upon my students copying “intellectual property” through plagiarism or sloppy citations. On the other hand, hadn’t I just guided my students to blatantly use digital media without any consideration of the author’s copyright? This hypocritical double-standard did not sit well with me. I needed to find a more balanced approach.

On one side of the spectrum, a growing number of individuals believe information should be openly available to copy, distribute, and modify despite copyright status, a position known as the copyleft. The growing copyleft movement provides a legal solution that enables authors a balance between copyright and public domain. For example, Creative Commons offers a wide range of tools to legally license intellectual property to be freely distributed, reproduced, and modified. Social media sites like Flickr take full advantage of Creative Commons licensing. Other websites like Pics 4 Learning offer copyright-friendly media and gather collections of royalty-free media available to the public domain, such as the Public Domain Database.

These resources are part of an effective and efficient approach to help navigate the complexities of copyright. I was relieved to know that my students could graze the commons of copyright-friendly and public domain media. Every now and again, my students wandered outside the pastures of public media, which prompted me to address the topic more directly. I still needed to know how to guide students who wanted to incorporate copyrighted material into their school projects.

Copyright & Fair Use Teacher Resources

In many ways, Renee Hobbs and the Media Education Lab of Temple University have spearheaded media literacy and shed light on how fair use should be applied in educational contexts. Not only is Renee’s scholarship quite forward-thinking, but her material speaks directly to a teacher audience. Take note of the linked videos—they inform as much as they entertain. Consider using these resources directly in the classroom with students.

PBS station KOCE of Huntington Beach, California has produced resources to support classroom teachers, including the “Copyright for Educators” series. This collection of videos and PDFs is quite detailed in the specifics of fair use doctrine, and it highlights what educators can and cannot do. These videos might be of particular interest for public school administrators who need to outline a district policy on fair use.

Lawyer and Harvard professor Larry Lessig speaks about copyright in his lecture “Laws that Choke Creativity”. This twenty-minute video covers everything from the original intent of copyright to how Web 2.0 technologies have challenged copyright law. His stories and examples are evocative and should be of high value to anyone with interest on the topic.

For Constitutional purists, take a gander at “§ 107. Limitations on Exclusive Rights: Fair Use” to see for yourself what started it all. Most contemporary interpretations of Section 107 stem from “The Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Media Literacy Education” developed by American University’s Center for Social Media.

Creative Commons has pioneered free licenses to content creators to publicly share work though a wide array of license options that allow others to reuse and remix for non-commercial and not-for-profit motives. These licenses offer more contemporary and flexible copyright options for both authors and users.

Copyright: Promoting Progress

In the summer of 2009, I came across the work of Renee Hobbs and the Media Education Lab through the Powerful Voices Institute held at the Russel A. Byerscharter school in Philadelphia, PA. The week-long institute brought together teachers from across the country, graduate students from Temple University’s education program, and students participating in the charter school’s summer media literacy program. Powerful Voices exposed this cohort to various critical thinking tools to deconstruct media messages, and the Institute also provided a repertoire of techniques to integrate the creation of media into the content areas.

In order to analyze media, we first needed to bring it into the classroom and under the microscope of critical thinking. On the flip-side, the Powerful Voices group needed an ample palette of media in various forms—audio, image, and video—to assemble our own media messages. The need to access media for educational purposes jettisoned the Institute right into the middle of the copyright dilemma I had previously encountered in my own attempts to bring technology into the classroom. Until then, I had always presumed the writ of copyright was intended to protect intellectual property through outright prohibition of the duplication of copyrighted works.

Renee Hobbs delved into the topic of copyright confusion. She pointed back to Section 8 of the United States Constitution that empowers Congress “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” This section protects the rights of authors, artists, and inventors to profit from their works within their lifetime. Without gainful pay, there would be very little incentive to write, create, and discover.

This notion challenged my unfounded assumptions that copyright was merely a tool for corporate gain. It made me question how academic progress protected under the U.S. Constitution related to my students and their media projects, especially if my students’ learning experiences by creating media messages wouldn’t compromise the owners’ ability to financially gain from our use of an intellectually protected work.

Copyright Section 107: Fair Use

Although I knew that Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution asserts our right to “Promote the progress of Science and the useful Arts,” I was still challenged by the question of whether my students’ use of copyrighted material to create their digital compositions was considered a useful art, or whether my students’ class assignments could be considered some of the intellectual progress the Constitution sought to protect. How could the writers of the Constitution know anything about my students’ needs to access and utilize digital media?

Further clarification is provided through the Copyright Act of 1976, Section 107 limits the exclusive rights of copyright owners for intellectual property to be analyzed, criticized, researched, commented, taught, or reported upon. This exemption is otherwise known as fair use. There are four factors that determine copyright infringement versus fair use:

- the commercial or educational purposes,

- nature of the copyrighted material,

- amount used compared to the whole, and

- the impact upon the profitability of the work.

Context is everything when determining fair use. For example, my students’ digital stories were for a non-commercial and educational purpose. The images pulled from the Internet were inserted into the movies in brief snippets. I hadn’t planned for my students’ movies to be displayed beyond our classroom, and therefore the use of those images would not compete against any profit potential of the original copyright holders. By observing fair use guidelines, my students were able to legally re-purpose copyrighted media for their own digital compositions.