Citizen Power: Capturing Images of American Work and Family Life

“We envision a future where society values care. To get there, society has to see care.” Working Assumptions

Introduction

There is a saying that a “photograph is worth a thousand words,” but what one reader of a photograph says about the image can be quite different from what another reader might say. Two people looking at the same picture can come to two different conclusions about its meaning. But understanding a photograph is not just dependent on what the viewer sees, it depends on what the viewer sees in combination with trying to understand what the photographer is trying to communicate. It is important to know that a photographer makes decisions, like artists or writers, about what to include in a photograph’s composition, and what not to include, and which photos to show the public, depending on what idea or message he or she wants to communicate.

This is especially true when viewing photographs produced with the goal of documenting specific events. The decision to publish, to make public, a specific image is dependent on what message or narrative the publisher or photographer wants to communicate. In this context it is helpful to know how the goal of the photographer, or the photographic assignment, guides the selection of a subject. This knowledge of purpose aids in our understanding of the photo, its meaning, and maybe its importance.

But the photographer or the publisher are not the only ones with a stake in what an image contains and communicates. We also want to consider how the subject of the photo might want, or not want to be, seen. When we are the subject of a photo, how do we want people to see us? What about our lives and our lived experiences do we want and not want communicated?

Two Photographs from the Great Depression Era

A good example of these ideas and questions can be seen by a close look at two photographs taken by the photographer Walker Evans. Evans was part of a group of photographers hired by the federal government’s Farm Service Administration (FSA), between 1935 and 1943, to document American life during this time period. For photographers working for the FSA the photographic assignment was to add actual faces to the statistics about the economic problems faced by Americans living in rural areas during the Great Depression. The photos were to document the powerful impact of the Great Depression on people’s lives. The hope was that the images would engender other Americans to care about the plight of people, fellow citizens, grappling with the impact of the Great Depression and years of poverty in their lives. And then use that care to gather support for New Deal farm aid programs drafted with a goal of improving those very same lives.

In the summer of 1936, while on leave from the FSA, Evans was sent by Fortune Magazine, with writer James Agee, to Hale County Alabama to document the lives of three families of sharecroppers. What Evans and Agee documented was later published in the book

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941). The photographs Agee and Evans included in the book told a story of poverty and hardship, their goal in writing the book. The historian Lawrence Levine tells the story of two photos taken by Evans for that assignment, one that was included in the book and one that was left out.

Levine writes,

In their account of three sharecropper families, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) James Agee and Walker Evans included many photos of the Burroughs family, including their widely reproduced shot of an unshaven, tired, anxious Floyd Burroughs in a tattered work shirt [see photo #1 below]. They chose not to use a picture that Floyd Burroughs requested they take of him, his arms thrown confidently around the shoulders of his smiling wife and sister-in-law, with his children posed in front, everyone looking clean and contented in their best clothing [see photo #2 below]. It was a classic family pose but not one congenial to the purposes of the book from which it was excluded…The fact that Burroughs, who seems to have no objections to the other photographs that were taken, wanted himself and his family pictured in this light as well, is an important part of the thirties that we can ignore only at great cost to our understanding of the self-images and aspirations of people like the Burroughs. (Levine, Historian and the Icon, p. 21-22.)

Photo #1

Photo #1 – Floyd Burroughs Source: Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, 1936, Walker Evans photographer.

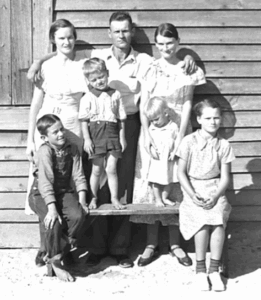

Photo #2

Photo #2 – Floyd Burroughs and Family Source: Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, 1936, Walker Evans photographer.

As Levine writes, Burroughs did not have any objections to photo #1, but wanted his family also pictured in a positive light as well (photo #2). He was willing to go along with the portrayal of his hard times, but also said there was more to his story.

Viewing these photos in the historical context – The Great Depression

As mentioned, a major purpose of the FSA was to gather support for New Deal programs that helped people get back on their feet who had been thrown out of work and were facing a lack of housing and food as a result of the Great Depression. But not all Americans agreed that federal government programs were the best solution to that problem. The debate around the best approach was at the center of the 1932 presidential election. Then President Hoover believed that problems of poverty and unemployment were best left to “voluntary organization and community service.” He feared that direct federal relief programs [providing money and/or jobs directly to individuals] would undermine individual character by making recipients dependent on the government.1 Hoover, though, was defeated for the presidency by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In his campaign for president Roosevelt put forth a different view of the role of government in solving these economic problems. He said, “What do the people of America want more than anything else? To my mind, they want two things: work, with all the moral and spiritual values that go with it; and with work, a reasonable measure of [economic] security–security for themselves and for their wives and children…I say that while primary responsibility for relief rests with localities now, as ever, yet the Federal Government has always had and still has a continuing responsibility for the broader public welfare…”2 More directly, Roosevelt argued, “…An American Government cannot permit Americans to starve.”3

Understanding the Great Depression

To help us better understand how the Great Depression might have impacted Americans on a more personal level, view this short video from the historian David Kennedy.

What does David Kennedy’s story about how the Great Depression impacted his father’s self-image add to our understanding of how Floyd Burroughs might have viewed his economic situation?

David Kennedy tells his story with the aid of historic photographs; what aspects of the story do the photographs help highlight and why do you think he wanted them included here?

Connecting to the historical context and questions of care and community

Stories and photos of family and work, both in the past and present, capture important moments in people’s lives and give us the opportunity to see beyond our own work and family contexts. They give us the chance to understand and empathize with others, seeing both commonalities and differences. And in doing so raise questions about the choices we make about who we care for and how. How far should our “circles of care” extend beyond our immediate family? To our next-door neighbor? To the homeless person we see on the street? To the person living in the next town? To a family living in another state? Another nation? And how, as we consider how far we extend our care, does this care get manifested? Are acts of care only personal actions, or are acts of care something for a community, state, or nation to take on together?

These questions of who we care for, and how, were central to the 1930s debate over the role of government in addressing the economic challenges of the Great Depression, and are still central to our public conversation and policies around such issues as health care, child care, minimum wage, the environment, and homelessness.

Circles of Care

With these questions in mind let’s re-look at the two Burroughs and photos and consider what Levine’s story, and its historical context, reveals about the “circles of care” questions raised above.

- Why do you think Burroughs wanted his family photo (#2) taken? What did he want people to see about him and his family through that image?

- Why do you think Burroughs didn’t object to the other photo taken (#1)? What else might he have wanted people to know about his life?

Given your responses to the above two questions, speculate on what Burroughs might have thought about the 1930s debate around the role of government in helping people.

- Would Hoover’s argument have appealed to him? Explain why or why not.

- Would Roosevelt’s argument have appealed to him? Explain why or why not.

In considering the role of the FSA Levine concludes,

“The photographers may have set about documenting the immediate impact of the severe economic depression, but they succeeded in creating a remarkable portrait of their countrymen’s resiliency and culture…In these photographs…we are made witness to a complex blend of despair and faith, dependency and self-sufficiency, degradation and dignity, suffering and joy.” (Levine, P. 27)

Is Levine’s argument supported by the two Burroughs photos? Explain your response.

Farm Service Administration Photos and Reflection

Examine the following sampling of other famous FSA photos and use what you see to support or revise your response to question #4.

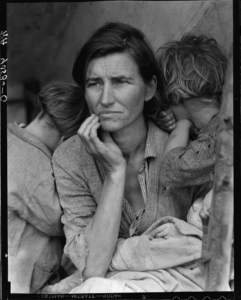

“Migrant Mother” – Dorothea Lange, 1936

Along the highway near Bakersfield, California. Dust bowl refugees – Dorothea Lange, photographer, 1935

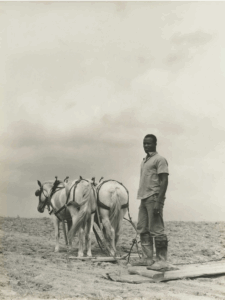

Tenant farmer, Lee County, Mississippi, Arthur Rothstein photographer, 1935.

Dust Storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma, Arthur Rothstein, photographer, 1936.

Unemployed coal miner’s daughter carrying home a can of kerosene. Marion Post Wolcott, photographer, Scotts Run, W. Va., 1938

Greene County, Georgia, Jack Delano photographer, 1941.

Making Connections

Connections to your own photo assignment – how might what was learned from this lesson connect your own photo assignment. Who are the subjects? What are their goals and what are yours? What do you want to make public and what do you not want to make public? Etc.