Curators notes:

In this resource, Mitch Nobis presents a unit created with his HS Juniors to help his very word-focused students bring a critical eye to visual imagery. As he explains, comics came to the rescue. On April 9, 2013Summary:

Mitch Nobis of the Red Cedar Writing Project sees a growing need for critical visual literacy in a multimodal world, and so he takes his students on a one-week exploration of learning about, creating, and analyzing comics. Included are lesson plans, resource links, and student work examples. Originally published on April 9, 2013A Closer Look Shows a Different Crisis

The media insists that the American educational system is in a state of crisis, but this is exaggerated at best and a total load of malarkey at worst. Schools in America are achieving as well as or better than ever before—an argument made quite well by Paul Farhi at the American Journalism Review. That said, while the perceived struggles are just that—perception, not reality in most cases—a different gap is revealing itself before our eyes, literally.

My juniors in Advanced Placement English Language and Composition are excellent analysts of alphabetic texts and can decode the rhetorical techniques in essays and speeches with the best of them. They are a hard bunch to persuade (I hope) because they see the argumentative moves being made behind the curtain, but when faced with visual texts like advertisements, the students are more easily swayed. As more writing lands in multimodal digital environments, this suggests a real potential crisis. Often, students don’t see visual texts as “texts,” and the students can be an uncritical, or at least less critical, audience. In a culture where campaign ads sway poll results and successful beer ads lead to sales spikes (among many possible examples), we need to boost our teaching of critical visual literacy.

But how? We humans learn best by doing, yet it’s hard to squeeze active lessons into curricula bursting at the seams to meet local, state, and national curricular standards and requirements. Teachers have lost an immeasurable amount of hair dealing with the problem of meeting both best practice and detailed, often inauthentic, external standards. Many of the newer standards, Common Core included, do mention visual literacy, though. Maybe we can “kill two birds with one stone.”

Critical Pictures: Page 2, Comics to the Rescue

The old and oft-maligned genre of comics offers us one possible answer and a unique way to include visual literacy without having to wildly alter the classroom curriculum. Here’s how it worked for me.

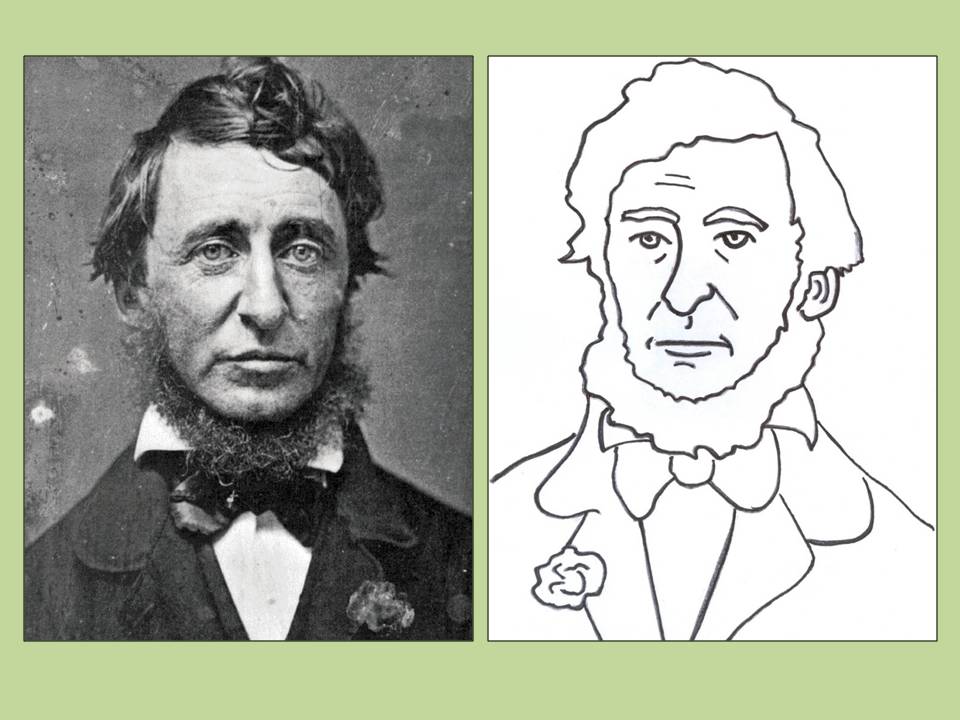

My AP Lang class reads Henry David Thoreau’s essay “Civil Disobedience” as an anchor text in a short synthesis unit about the freedom of speech. In the past few years, I’ve taught a visual literacy unit focused solely on analyzing print advertisements, but it was a stand-alone unit, disconnected from the curriculum at large. In an attempt to streamline instruction and help students better see the connections between composing alphabetic and visual texts, I revised the lessons to fit alongside Thoreau.

In short, the unit took one week* and went like this:

Students were asked to…

-

- read and thoroughly annotate Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience.”

- write a rhetorical analysis of the three pages in “Civil Disobedience” when Thoreau describes his night in jail.

- read an introduction to visual literacy that covers elements and principles such as lines, shapes, colors, the rule of thirds, and more. (On this note, Frank Baker’s website has a host of helpful materials.) Apply the elements and principles by analyzing a print advertisement alongside the introductory reading.

- read and discuss an article from Salon about free-speech zones at the Republican and Democratic national conventions during the 2012 presidential campaign.

- conduct an analysis of the visual rhetoric of the article’s accompanying photograph that shows numerous police suited in riot gear.

- read and discuss an editorial cartoon by Ruben Bolling about free-speech zones and the Founding Fathers.

- review the basic terms of comics authoring.

- discuss and analyze the visual literacy and comics techniques used by Bolling.

- follow Nick Kremer’s Digital Is resource to guide them as they create comics versions of a scene from Thoreau’s jail excerpt. We also looked at comics by Matt Feazell for good examples of how even stick figure comics use elements and principles of visual design to influence an audience.

- write a reflection analyzing their own visual-rhetorical decisions as authors.

* This process took one week in an AP class, and we were only able to do it that quickly by doing steps one, three, and nine as homework; it would likely take longer in a non-AP class with lower homework requirements.

It is important to note that without the emphasis on visual literacy in this lesson, students would still read and analyze the same pieces on freedom of speech. The analyses of visual elements and making of and reflecting on the comics are the new components of the lesson, but they really only moved there from the advertising lessons. Ultimately, not much of this was new to my AP English Language curriculum, only moved to streamline the curriculum, to help students make connections among the lessons, and to invite students to actively use critical visual literacy skills.

Critical Pictures: Page 3, The Students’ Comics

A range of students’ comics are linked here, with two also posted below. Their comics vary widely in artistic quality, but that is fine. The elements we practiced don’t depend on aesthetics. The student samples show the range, from stick figures drawn in pencil (fig. 1) to more polished work that uses color (fig. 2), but all of them show students trying out elements of visual design: zooming in to show emphasis or zooming out to give the setting, making some character bigger or smaller to show dominance, using color to draw attention to specific details, and more.

Most of the student samples posted I consider to be “good ones.” Rest assured, as with any assignment, there were some clunkers in the mix too, but even though those students may not have put as much thought into the visual design, they still gained new perspectives by working in an unfamiliar genre, at least. Even if some students didn’t vary the size of the panels in the comic, they still had to think about what to include inside each panel, which is an important rhetorical decision in itself.

Critical Pictures: Page 4, Analog By Design

Students need critical awareness of visual rhetoric for a variety of reasons, but one big reason is the increase of time spent in digital environments where visual elements mix readily with traditional text. Comics might seem like an antiquated response to this need, but making comics allowed us to explore the basic elements of visual literacy in only a week. If we had more time, I would gladly extend the lesson to include digital modes like websites or video projects. Given that one of the motivations for this activity is to prepare students for critical reading of digital media, why not use digital media in the activity? Some colleagues have asked me why I don’t just ask the students to use one of the many online comics creator websites. After all, we could have made comics in just a couple minutes, right?

Right, but we learn best by doing, and ultimately, I wanted my students to think through the authorial decisions and visual rhetoric at every stage. With a hand-drawn comic, the students had to think about the overall layout of the page, the degree of zoom and camera angles for the various panels, how to mix words and pictures enough to keep the reader interested while also conveying necessary information, and more. Making just a one-page comic of one scene of Thoreau’s essay became a series of deep rhetorical decisions.

Unfortunately, making digital comics with pre-set options would not allow for the same experience. Such websites are useful, but I do think that because we learn best by doing, in this case going analog with pencils on paper allowed students to more fully explore how visual design—something as simple as the degree of shading or whether the camera angle is from above, below, or at eye level—can persuade the audience. These design decisions are usually made for you when using a comics creator website.

Critical Pictures: Page 5, Did It Work?

The student reflections suggest tremendous growth. Though few of them claim joy at being assigned Thoreau’s essay in the first place, they clearly put thought into the visual rhetoric of their comics. Here is a sampling of comments from their reflections:

-

- I made a point to emphasize the quirky comfort that Thoreau felt in prison [by showing that the prisoners’] expressions are content.

- The dialogue panels are generally parallel to the two characters having the conversation because a neutral angle shows balance in authority and friendship.

- [I used only] black and white to represent the plainness and simplicity of Thoreau’s jail cell.

- One tactic I used was color—blue for things Thoreau thought were good and red for what society thought was bad/taboo.

- I varied the size of the panels to address importance.

- I used sizing to represent the small, common man vs. the government system.

- I dressed the jailer in all black to make him seem intimidating. I also drew the jailer a bit taller than both Thoreau and the cellmate to help convey this feeling.

- I zoomed up close to [Thoreau’s] face to show the importance of his thoughts about his fellow townsmen and women. Then, in the next box, I showed him walking on a different path than the rest of the people to show his independence as a thinker.

- Finally, in the last panel, when Thoreau leaves jail, he and the people around him are the same size to demonstrate how [jail] wasn’t that big of a deal.

- As for the writing, I wanted to make it simplistic because “Civil Disobedience” is very lengthy and difficult to put in a comic. I used key details from the text instead, the parts that I felt were most important.

Though the unit was only one week long, the students were able to clearly explain how visual texts from advertisements to photographs to comics influenced them as an audience. The language gained from the visual literacy introduction gave them the tools to analyze and explain those visual texts. Instead of just saying an advertisement made the product “look cool,” they could now explain that “the ad used the rule of thirds” to grab their attention and “emphasize the product.” There is certainly more work to be done, but this activity served as a solid introduction to critical visual literacy. It allowed the students to enter the discourse of visual texts.

Critical Pictures: Page 6, Conclusion

Taking it to the authorship stage by making comics was clearly valuable. Their written reflections demonstrated the creativity and insight they used in making the comics. What on the surface might look like hastily drawn comics now look like thoughtful first drafts, or thumbnails. I would love to see what they could create with more than one day to make the comics.

Also, as I watched my students work, I realized an unforeseen benefit to making comics instead of a different type of visual text like a poster or public service announcement. Because comics feature a series of panels instead of one large picture, the students had to plan and consider the rhetorical impact of as many as ten visual designs instead of just one. Making comics naturally provided them with repetition and practice. We already know that practice leads to perfections, that student writers need to write often to become better writers. There’s no reason the same wouldn’t be true with visual rhetoric as well. By making comics and designing the numerous smaller visuals that make up a comic, students were able to refine their visual rhetoric within the space of a single assignment.

This unit leaves the students with a cursory introduction to visual rhetoric, but even a brief glimpse behind the curtain is better than none. Another unintended benefit to moving the visual literacy study to accompany Thoreau is that it gets the visual rhetoric terms and concepts into my curriculum earlier in the year than it was before, so although the unit is short, we can now refer back to it for the remaining three months of the year instead of three weeks.

It’s only a start, but it’s one that gets students thinking critically about the images thrust before their eyes every day. Ideally, the next time a campaign ad tries to convince them that a candidate is evil by darkening the shadows and moving the camera angle, my students will recognize it as the visual fallacy that it is. They will not be swayed by shoddy visual rhetoric, and maybe, just maybe, they will vote based on the candidate’s education platform and not the opponent’s advertisement.