I Love My City: Youth as Community Problem Solvers and Creators in 21st Century Classrooms

Transformation is not something that happens overnight.

This year, my high school seniors completed research projects that asked them to answer the question, “what problem do you see in your community, and what do you wish to develop in order to address this problem?” Getting them to ask relevant questions took time, and creating a space where they felt empowered to love their community enough to want to restore it required patience and a re-prioritizing of sorts for myself as a teacher.

When I first began teaching, I felt that it was important to connect what we did in the classroom to the “real world”, and for my students, as individuals, to be able to look at such a world critically. However, after a few years of teaching in Detroit and watching unemployment swell, dropout rates increase, and the overwhelming effects of poverty debilitate and divide the families I served, I realized that it was not enough for my students to participate in what I deemed as transformative practices on an individual scale or in isolated instances; the institutions that surrounded them needed to be transformed as well, and it was time- as I saw it, for us to develop a sense of collective ownership in creating the changes necessary to turn our city into a place of hope- a community that worked for us.

This process took over a year, but it is one that strengthened relationships, grew creative capacity, and helped students to use media in new and powerful ways to speak back to those forces that fettered them to a narrative that painted them as anything but leaders in their dying city.

The Process

The process

My colleagues and I began 11th grade year (1 year prior to the research project) with a series of interactive, whole-grade lectures/discussions that exposed students to the portrayals of Detroit in the media, specifically in Time magazine. While many of these images were problematic, sensationalized and biased, we thought that engaging students with this content would be a valuable opportunity to pose powerful questions to them about how they saw their community and their role in rebuilding it.

In addition to this, we slowly introduced students to employing critical lenses, immersing them in activities and discussions that required them to examine how social, political, and economic forces helped shape the way we read the world and the word. Students began to question why most images in newspapers at the time showed Detroit in such a negative light, and why- although 90% of the city is comprised of African-Americans, those who were painted as “heroes” looked nothing like them, and most were male.

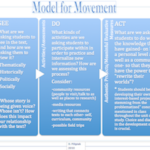

It is in this place of critical inquiry and curiosity we began our journey, and my colleagues and I revisited our British Lit curriculum often to consider how to best make changes that would reflect our growing commitment to community and critical pedagogy. We designed several projects that allowed students to bring the community into the classroom, and I also developed the “Model for Movement”, a model that articulated- for me- how I could move students from reading texts critically in the classroom to ACTING critically in their neighborhoods and communities.

The activity of the eleventh grade year, then- laid a strong foundation for the assigned research project the following year, and motivated students as community problem solvers and creators, roles that they were not previously used to playing within a school setting. While this was not a seamless process, I learned how to more effectively marry critical and community minded pedagogy to district standards and requirements, and became more intentional in my attempts to do so. Furthermore, I am now convinced that work like this is not only powerful in the classroom- but necessary.

Model For Movement

The “Model for Movement” was my attempt at articulating what “problem-posing pedagogy” (Freire) could look like in my classroom. I wanted to get away from what Freire calls the “banking” or traditional model of education where I was the expert, and move toward creating a classroom where students could co-construct knowledge with me and present the fullness of their realities and communities in a critical manner.

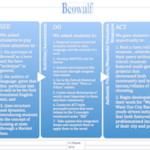

The above screen shots capture both the explanation of the model as well as an example of one that I created for an 11th grade unit that featured Beowulf as its anchor text. Please look below for a document link to this, which contains a blank template to fill out for your own use if you’d like.

Hero/Villain Museum

Hero/Villain Exhibit: Student featuring those who feed the hungry as heroes/sheroes.

For this exhibit, my colleagues and I asked students to create 2 multigenre projects:

- Highlight a villain or hero from Beowulf and visually express, to the reader/viewer, why you define this character as either a hero or villain.

- Highlight a villain or hero from the Detroit area (real-life person) and visually express to the reader/viewer why you define this person as either a hero or villain.

The entire school was invited in to view our museum and ask questions about students’ work.

Before this exhibit, students:

- Read Beowulf and discussed “Hero Archetypes”, and focused specifically on Marxist and Feminist readings of the text.

- Attended a Detroit Historical Museum exhibit entitled “Hero or Villain?”, which highlighted Detroit figures and who were well known for both “heroic” and “villanous” behavior and actions. Students took notes on 3 people and shared out in groups.

- Wrote a persuasive paper about a chosen figure from the exhibit, highlighting reasons that person was, indeed- either a “hero” or “villain”.

We Want Our City Back

“We Want Our City Back” was an event that grew out of the discussions we had about the way national and local media portrayed Detroit, students overwhelmingly felt that coverage was biased and that individuals named as heroes in Time magazine were not enough.

With this in mind, we decided to ask them what they thought the city needed, and based upon their responses, created focus groups for assigned photojournalism projects:

- Raise Your Voice– a group attempting to combat negative “images” of the city via the media in print, photographs, discussions

- Crime Fighters-Group looked at violence and other issues that students viewed as a crime, such as having a lack of health care, not having access to grocery stores within their neighborhood, or when faced with an emergency- having no emergency responders or a delayed response

- Power in the City-Students presented both scandal and abuses of power, authority and trust, as well as ways that they thought power in the city could be redistributed.

- Building Bridges– Students looked at segregation in the city based upon race, class, gender, religion, age, socioeconomic status

Once students completed their photojournalism projects, they arranged them on boards for presentations, created resource binders to educate others about their issue, and brought these resources with them to a summit, where they interacted with invited speakers around the issues at hand.

Student Research Projects

The research process that students participated in looked like this:

Summer work prior to Senior Year:

Students were asked to think about an issue that concerned them in their community, and to devise a possible project to address it. They were also instructed to bring in a list of resources that might help them begin the research process in the fall. Lastly, students were asked to think about how their ten-week internship placement during their senior year (a part of our school’s model) could align with their research project. While the initial project ideas developed during this time were flimsy, the goal was to get students to think with the end in mind, and for teachers working with them to have an idea of what drove the student’s interest.

Research Paper Process:

Brainstorming, one-on-one and group discussions, data collections and interviews, data crunching, outlining, rough drafts of papers. This was the “meat” of the project. Most students took quite a bit of time developing a research question. Many were frustrated initially because they expected to have a question right away, not realizing that they had to look at their interest, read, summarize, read some more and crunch. I spent 2 out of 5 weekdays conducting one-on-ones with students, and agreed to print research articles that they found on Google Scholar but couldn’t access during this time. I also spent much of this time asking questions to help guide students through their work and to affirm them, as there were many points where they became frustrated, confused, and might speak up, “I don’t care about this anymore,” or “I don’t get it, I don’t get what I’m tryin to say”, or “I can’t find what I’m lookin for!” It was important to keep a positive culture in each classroom during this process so that it didn’t crumble, and building personal relationships with each student through these conferences seemed to achieve that purpose.

I handed out packets that required them to summarize articles, document important data or quotes, offer conclusions, and include citation information. This is what students worked on during conferences and at home. Once students collected all necessary info, they were asked to find trends btwn data, and gradually moved to constructing a research paper. Revision and editing time were built into this as well.

Project

Students submitted project proposals, which included rationale based upon their research as well as a detailed plan and timeline that communicated how and when they were going to fully implement their project.When teams of teachers approved their projects, they could proceed with their work and carry out the necessary steps required for completion. Students finished projects and wrote reflections, sharing their work with their peers and community members who helped them develop their projects.

Research: Self Esteem in Young Women of Color

Senior Year Research Project Reflections

Teen Sexual Health

Senior Year Research Project Reflections

Abandoned Buildings in Detroit

Senior Year Research Project Reflections

Urban Education Issues

Senior Year Research Project Reflections

Effects of Poverty

Senior Year Research Project Reflections

Misunderstood Forms of Artistic Expression

Senior Year Research Project Reflections

What is Youth’s Role in Rebuilding Community

Senior Year Interviews

What Obstacles Stand in the Way of Youth Achieving Their Dreams?

Senior year interviews

What is Your Mission?

Senior year interviews

Final Reflections

This is one student’s reflection after his 11th grade year, after exposure to critical theory and engagement with community centered projects.