Curators notes:

This resource highlights the COURAGE that one high school English teacher exhibited as she experimented with integrating Twitter into her classroom during Socratic Seminars. It demonstrates how risk-taking with new media tools can initially produce fear but eventually offers benefits by engaging students in new ways and spurring teacher creativity.Summary:

Laurie Roberts of the Boise State Writing Project takes us through her Twitter experiment in which she incorporates tweets into her Socratic Seminar for the first time. Included are instructions, expectations and final thoughts.Taking risks has never felt like a natural part of my personality. I don’t typically blaze my own trail. I look for the safe, the comfortable, the experiences I can control.

This is as true in my professional life as my personal. However, this risk-averse tendency is often in conflict with another aspect of my character: the desire to improve myself—to improve my craft. This desire manifests in my classroom with my career-long need to create new units and lessons (or, at the very least, to repeatedly revise old ones). One of the greatest challenges and joys of teaching is that no lesson or unit ever feels like it’s done. There is always room for improvement. I have come to believe this is how it should be—that this constant cycle of creation and revision is actually the hallmark of any teacher who is experiencing moments of greatness.

On the other hand, I don’t endorse change simply for the sake of change. I pursue the new when I see the potential for it to be better than the old. This premise is particularly relevant when it comes to using technology in the classroom. I am not interested in using technology just because it’s the latest, coolest thing to do. I want to use technology when it will make my classroom more effective, when it is pedagogically sound, and when it allows me to improve instruction and increase learning.

And so, I come to the Twitter experiment.

On Monday (October 13th), I am going to integrate Twitter into my usual Socratic Seminar method. Simply put, Socratic Seminar is a student-led discussion. Specific protocols exist for the Socratic Seminar, and, like many teachers, I have tweaked this protocol to suit my classroom.

I typically use Socratic Seminar as a discussion protocol at the conclusion of teaching a classroom novel. In my classroom it works like this:

-

- The day before the seminar, each student generates a specific number of discussion questions (typically 5). They also answer their own questions in writing (or trade questions with a partner and answer his or her questions).

- On the day of the seminar I create an inner circle with enough desks for half of my students. As students enter the classroom, I let them decide whether to sit in the circle or outside of the circle (they know that eventually everyone will be in the circle).

- Before the seminar begins, I review expectations and etiquette (all of which has evolved over the years, and will undoubtedly continue to evolve): participate; hand raising is optional (because some students just can’t give it up); speak one at a time; look for ways to bring others into the discussion; disagree in an agreeable way; students outside the circle silently observe, listen, take notes, adding to their previous questions and answers, etc.

- The inner discussion begins with a volunteer posing a question, and it continues until I call for a rotation from inner to outer (and vice versa, of course).

For more than a year I have contemplated adding a Twitter component to this process. For more than I year I have let my fears of what could go wrong stop me. For more than a year I have been unable to dismiss the idea that my Soc Sem could be better, if I could engage that outer circle in a more authentic, more interactive form of feedback.

(As a sidenote, I know that a lot of teachers have effective ways of engaging that outer circle—often asking them to evaluate the participation of a particular member of the inner circle. If that is working well in your classroom, kudos to you.)

So here is the somewhat-fuzzy, work-in-progress plan for Monday:

-

- The inner circle will proceed as usual.

- The outer circle will still be silent and they will still be able to pursue the kinds of activities they have always pursued. But now they will also “live tweet” the inner circle discussion.

- I will have my Twitter account projected on the whiteboard, with the feed set to our class hashtag: #robertsAP15

- Outer circle students will be asked to use their phones or other devices to tweet at least three times.

- I will offer suggestions for the content of these tweets: quote someone whose comment resonates with you (basically a version of retweeting), quote and add your own idea or your own counter-claim (retweet and edit), ask a follow-up question, answer a question currently being discussed.

- I will provide eight chromebooks for those who have a twitter account but no smartphones.

- For those who don’t have (and don’t want) Twitter, I have two options in mind: write your tweets on the whiteboard using a marker; write your tweets on sticky notes or your own paper to be turned in to me later. (I see this as an option for those students who sometimes feel intensely reluctant about going public with their writing or their ideas. I like to think this option is one that I can gradually eliminate.)

Call me crazy, but this just might work. Or it might be a horrible, chaotic mess.

Just to up the ante, I have invited my administrators to come watch, as well as a few colleagues. I promise to write a follow-up blog entry, regardless of the outcome. I might even do some live tweeting myself.

Follow-up: The Twitter Debrief

If you read last week’s entry, you know that I decided to take on a new risk in my AP Literature classes last Monday: integrating Twitter into my classroom discussion (specifically the student-led discussion known as a Socratic Seminar).

Let me just start by saying that this was not perfect, but it was better than I imagined it would be, and I will definitely do it again.

This was to be our first Socratic Seminar, so I needed to spend some time giving instructions, as I always do, with the added element of explaining how the live tweet portion would work. I also wanted to make sure that I had time for at least two fifteen-minute discussions to happen in the inner circle. I feared that a 52-minute period would make this a challenge (down from 59 minutes last year, since we switched from a 6-period to a 7-period day), but as it turned out, the timing was just fine. It took me about five minutes to explain the protocol for the inner circle (see last week’s entry here) and another five to explain what would be happening in the outer circle.

I have a confession to make: I often put things off until the last minute. It wasn’t until I got to school on Monday morning that I settled on my exact plan for the outer circle. In fact, about 12 minutes before zero hour was to begin, I was finishing up a newly conceived “Socratic Seminar Checklist” that I wanted each student to have. The copy machine gods smiled upon me, and I was able to make 150 copies of my checklist and get back to my room with four minutes to spare. Whew!

As I drove in to work on Monday, I recalled a conversation with my brilliant colleague and friend, Rachel Bear. She suggested to me a few years ago that if Socratic Seminar is a pedagogically effective tool, it shouldn’t have to be graded at all. In other words, if it is creating an atmosphere for authentic and effective discussion–discussion that is giving students a chance to deepen their understanding of the work and preparing them to write about their deepened understanding–then those outcomes should be reason enough for them to participate.

Of course Rachel is right about this . . . but that doesn’t mean I was ready to entirely let go of the graded portion of this discussion. It did mean that I was ready to put the responsibility for keeping track of participation onto my students. Hence the checklist:

Socratic Seminar Checklist

As I said before, I love this checklist. I love that it freed me from the tedious and distracting practice of tallying student participation. I love that it was yet another chance for me to tell students “I trust you. I expect the best from you.” And finally, I loved that it became a handy place for students without smart phones or other devices to write their “tweets.”

When the discussion began in zero hour, I must admit I was pretty anxious. Would they tweet? I am pleased to report that they did indeed tweet. It took a few minutes, of course, but before long, they were tweeting, using our class hashtag (#robertsAP15). They were asking questions, answering questions, and quoting (retweeting) comments that were being made in the inner circle.

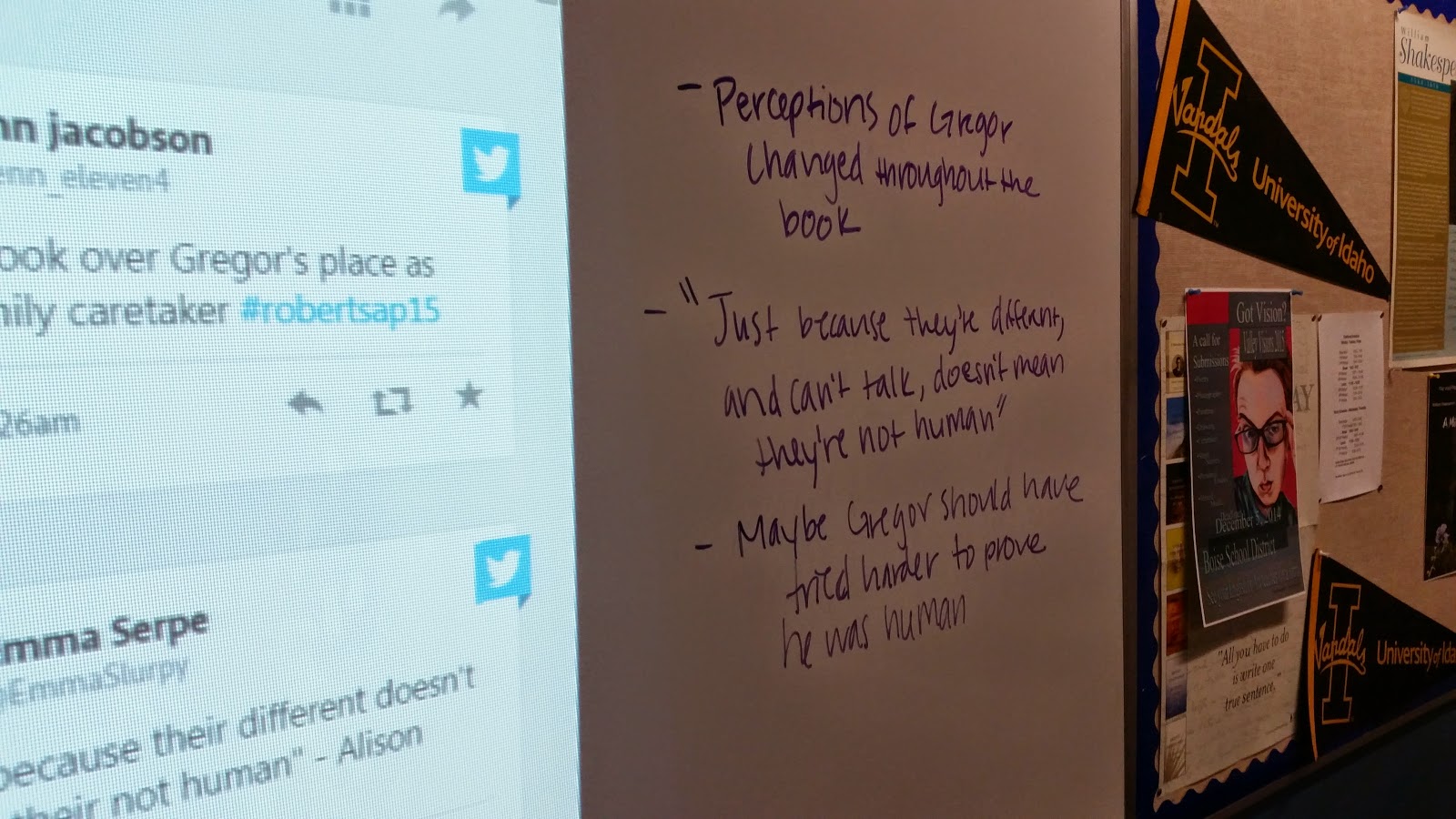

Honestly, it was exhilarating. One student from zero hour wrote his tweets on the whiteboard, next to the display of virtual tweets, and in that moment I began to see exactly what I had hoped for: the old and the new techniques were working together–were merging into something that was even better than I had pictured. This whiteboard tweeting continued throughout the day:

I also wondered if the tweeting (especially the tweets showing up on the whiteboard) would bring too much distraction to the inner circle. I am pleased to report that this did not seem to be a problem. Of course this is based on my subjective perception, but I felt that the conversation had a typical ebb and flow, in no way stymied by the additional stimuli in the room. On a few occasions someone in the inner circle would actually note a question or comment from the twitter feed and pose it to the inner group for discussion. I found these moments quite satisfying and not at all chaotic.

To pull this off, I made several decisions regarding protocol, and I am almost entirely pleased with how these worked out:

-

- Inner circle members are not allowed to tweet (their devices must be put away).

- Outer circle members are not allowed to talk.

- Students could tweet using Twitter, writing on the whiteboard, or, if they wanted to avoid going public, they could write three tweets on their Checklists. (I am toying with removing this last option in the future–or at least limiting it. I really want to push them into making their comments in a public forum at some point–whether on Twitter or on our board.)

- I projected the tweets on my board throughout the discussion. At first I did this through my Twitter page, which I had open to our class hashtag. This page was slow to refresh, so during my second class I switched to tagboard.com, another platform for displaying tweets connected to a particular hashtag. I liked the look of this platform (you can see the boxes in the pictures above), but I was still frustrated with the delay in updating new tweets.

I’ll try to wrap up with some final thoughts:

-

- The vast majority of my students loved this. When I asked for their feedback they said that they felt the outer circle was suddenly as important as the inner. They loved the various ways of sharing their ideas. They wanted to listen closely to the inner circle, so they had things to tweet.

- Several students tweeted early in the day–before coming to my class–about how excited they were about this. One student came in at the beginning of 2nd period with a sad look on his face. He was going to miss the whole class for a dentist’s appointment. I encouraged him to enter the Twitter feed later, if he had a chance, and 20 minutes later his tweets were showing up on our wall.

- I did not anticipate how much my colleagues and friends would enjoy our day. Several followed along and a few even engaged in the conversation. Once I assured my students that these weren’t random weirdos, they were actually intrigued by their interest in the conversation (my repeated joke: “they’re weirdos, but not random weirdos. They’re my friends”).

- Some of the tweets were more silly than serious–clearly going for the laugh rather than thinking deeply. I even had a few selfies enter the feed. Frankly, I could have addressed this issue better beforehand, and in the future I will. But honestly, it was a very small percentage who took this approach, and I want to err on the side of freedom and joy, rather than put very strict, serious limits on them.

We will be doing this again following our completion of Camus’ The Stranger week after next, and I know that my students are excited, as am I. Undoubtedly it will continue to be a practice that needs some tweaks, and I suspect it might look very different in a year or two, but for now, it is a risk I will gladly take again.