Writing With Pictures: Creating Comics in the Classroom

Curators notes:

In Writing With Pictures, Nick Kremer presents a lesson and associated resources that helped his students see "what makes a comic book 'tick.'" On July 11, 2012

Introduction: Language Arts is, at its core, about teaching students to effectively express themselves and to accurately interpret the communication of others, so I’ve always thought that divisions between English and Art were arbitrary and counterintuitive. Both use the same tools – connotation/denotation, critical thinking, inferences from context clues, cultural influences, creative elements of “craft”, etc. – they just seem to speaking different dialects. English primarily concerns itself with written and oral language, and Art primarily with visual language (if you don’t consider visual iconography a language, no further remedy is necessary than “reading” Shaun Tan’s The Arrival…but more on that to come!).

As a beginning teacher, I thought there was no better way to cross the bridge between these two disciplines with my students than through the medium of the graphic novel, a literary form whose merit has long been unduly denied.

As a fairly avid reader of comic books growing up, the medium has always had a place near and dear to my heart, so I was always a bit surprised to encounter the disdain and contempt held by academia for what was perceived to be an inferior form of literature. Many dismissed the medium as un-intellectual and thus unworthy of further thought, and of those who did take the time to consider comics, it was typically with a breath of mild contempt for “short changing” students of genuine literacy experiences.

I felt at the time that this couldn’t be true; many of my geeky collegiate friends had also been (and still were) comic book readers, and they turned out just fine. Furthermore, didn’t almost all of us start out with picture books as a point of entry into the wonderful world of literacy? Thankfully, I entered education at a time when research was finally starting to catch up with my claims. Work within the last decade by Michael Bitz, Dr. James Bucky Carter, and Dr. Katie Monnin, among others, has started to document the many benefits of using comics in the classroom, and they are wide-ranging.

Expectedly, many struggling readers find graphic novels to be more engaging than their non-illustrative counterparts and more in-tune with the various other types of visual media kids are currently consuming in our culture (television, film, video games, etc.). Equally expectedly, as these students become active readers of graphic novels, their literacy skills improve: they learn to visualize texts internally as they read, appreciate literary techniques, acquire vocabulary, reinforce traditional grammar and spelling, and foster an overall love of reading.

Comics are more than a remediation tool, however. As critics take the time to sit down with a copy of the best this medium has to offer – Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust memoir, Maus, Alan Moore’s deconstructive and dystopian Watchmen, the aforementioned archetypal immigrant story, The Arrival, to name a few – instead of blindly attacking the worst available (titles which are often meant to be primarily commercial entertainment; you don’t see efforts to ban the novel as a literary form from just because of the existence of a plethora of Judith McNaught romance paperbacks), they will realize that comics have a lot to offer. They force readers to critically analyze both what they see and “hear,” to draw inferences about what occurs between panels, to experience symbols and metaphors and juxtaposition and a litany of other literary elements in extremely overt forms, and to navigate trans-mediated forms of composition.

There are benefits and drawbacks to any literary form; the writer should have a full palette at his disposal for conveying his message. So with that in mind, early in my teaching career, I decided to bring comics into my classroom by adopting the same tried-and-true method I had for getting students to appreciate any literary form we studied: to transform them into poets or playwrights, or in this case, graphic novelists, with creative license and aesthetic ownership of their own authentic content. The following lesson is the same framework by which I exposed my students to what makes a comic book “tick”, and will hopefully leave you with a greater appreciation and understanding of the complexity of the medium. Grab a paper and pencil – and enjoy!

Writing With Pictures: Step 1 – Formulate a Narrative

Step 2: Think Visually

A trait shared by all good writing is its descriptiveness, its ability to invoke intended sensory experiences in its readers. When we read a traditional prose text, we often visualize it in internalized images. In fact, students are quite used to finding and discussing the specific language that evokes these visualizations in our ELA classrooms. Therefore, illustration is a fairly natural extension of what already occurs in the reading and writing process – it is merely making explicit what already exists implicitly.

INSTRUCTIONS: Carefully re-read your text. As you do, keep a running list of every image that enters your mind as you read. You may find it useful to highlight or underline (and numerically notate) the specific language that evoked each image. Think of yourself as a photographer in the story, taking “snapshots” of everything worth reporting.

Writing With Pictures: Step 2 – Think Visually

Step 2: Think Visually

A trait shared by all good writing is its descriptiveness, its ability to invoke intended sensory experiences in its readers. When we read a traditional prose text, we often visualize it in internalized images. In fact, students are quite used to finding and discussing the specific language that evokes these visualizations in our ELA classrooms. Therefore, illustration is a fairly natural extension of what already occurs in the reading and writing process – it is merely making explicit what already exists implicitly.

INSTRUCTIONS: Carefully re-read your text. As you do, keep a running list of every image that enters your mind as you read. You may find it useful to highlight or underline (and numerically notate) the specific language that evoked each image. Think of yourself as a photographer in the story, taking “snapshots” of everything worth reporting.

Writing With Pictures: Step 3 – Closure

Step 3: Closure

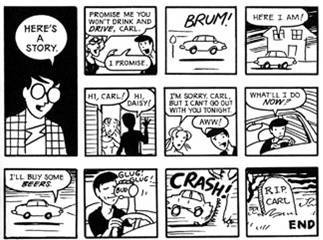

An essential literacy component within a sequential art narrative (the technical term for a comic) is closure – the often unconscious process a reader goes through of ‘closing the gap’ between panels (isolated images) of the story. Though images themselves play a crucial part of the narrative, it is the “gutter” that exists between these panels where most of the reading takes place. In the following video podcast, I illustrate how closure works in a comic and the degree to which it allows the author to control a reader’s perception of the narrative.

INSTRUCTIONS: After watching the podcast, go back to the list of images you generated from your text and consider the amount of closure between them. Add additional images at places where you feel the “jump” between images might be too confusing for readers to deduce on their own. Eliminate images where you feel redundancy or where you want to give readers imaginative license to reach their own visualizations of the story.

Writing With Pictures: Step 4 – Paneling

Step 4: Paneling

Once an author has identified the number and type of images he/she wants to include in a sequential art narrative, he/she must next consider how to lay those images out on the page. Paneling – the process of determining the size, shape, and arrangement of images throughout the narrative – not only controls the sequence in which those images are read, but also influences a reader’s pacing, perception, and point of view. The next video podcast highlights a wide variety of examples of paneling within professional graphic novels.

INSTRUCTIONS: After watching the podcast, consider various approaches to paneling the images of the visual adaptation of your text. On a series of blank pieces of paper, draw the lines of the various panels that will make-up each meta-panel (page). Lightly number those panels so that they correspond with your list of images. [Resist the urge to start sketching anything within those panels yet, though!]

Writing With Pictures: Step 5 – Encapsulation

Step 5: Encapsulation

With an outline of events and composition space now established, the author is next ready to encapsulate his/her images – to make calculated decisions regarding the manner in which to depict the characters, artifacts, and events of each panel. Much like a photographer, an illustrator must consider perspective, framing, and posture/positioning, all of which are explained in detail in the following podcast, using technical artwork from the great Will Eisner as examples.

INSTRUCTIONS: After watching the podcast, work your way panel by panel through you composition, bearing in mind the elements of encapsulation as you lightly pencil a rough sketch of each scene. Use only simple drawings – “stick people”, boxes, etc. – at this point to designate merely a general sense of the visualized final product.

Writing With Pictures: Step 6 – Lettering

Step 6: Lettering

Adding text to a sequential art narrative is as much a science as it is an art. There are formal rules for visual design and layout of text features (for example, external dialogue must be placed in a “balloon” while internal dialogue occurs in a “cloud”, and the placement of text features is read left to right, top to bottom on the page, conveying a sense of passing time within a single static image). However, aesthetics also come into play; the style and size of font, the use of bolding, italics, capitalization, etc. all contribute to the manner in which that text is read, helping to shape a reader’s perception of rhythm, tone, and auditory imagery. The next podcast will briefly expose you to a few different approaches to lettering.

INSTRUCTIONS: After watching the podcast, return to your visual narrative and draw in any narration boxes, voice bubbles, thought clouds, or sound effects needed to convey the textual elements of your composition. Write in the text as you go, experimenting with various aesthetic approaches to the language.

Writing With Pictures: Step 7 – Abstraction

Step 7: Abstraction

At this point, students have generated what is typically known as a “dummy” draft – a rough visual outline of what the final product should look like. To take it to final form, however, a few more creative decisions still need to be made. One of those decisions regards visual abstraction, the level of realism contained in an image. An iconographic representation of a character, object, or setting (a “cartoon”) is read in a very different way than a lifelike illustration. Generally speaking, the more abstract an image, the more readers identify with it at the conceptual level (an idea); the more concrete an image, the more readers identify with it at the perceptual level (a thing). The visual examples contained in the following video podcast will make this concept considerably clearer.

Abstraction can be exploited to great effect by an illustrator – if he/she has the technical ability to draw images in a manner that fits his/her vision. While I have found that originally-reluctant artists in my classroom often end up being much more skilled than they give themselves credit for, I have also allowed students to partner with Art classes in my school to “hire” an illustrator (in a manner that mirrors real-life) in order to craft a final draft, or to use photography or computer animation software to create digital compositions.

INSTRUCTIONS: After watching the podcast, determine the level of abstraction you want to utilize in your visual narrative. Go back and draw a final version of the images in each panel – or employ a talented artist (perhaps a family member or student) to do the illustrating for you as he/she listens to your artistic direction. Once a final draft is completed that meets your liking, “ink” the lines of each panel (with a pen or thin marker) so they stand out on the page.

Writing With Pictures: Step 8 – Coloring

Step 8: Coloring

The final step of the compositional process is to determine the desired shading and color tones that will help shape the atmosphere/mood of a visual narrative. In the professional industry, this choice has sometimes been compromised by financial factors – color costs more to print than black and white, so the variation and richness of colors available often depends on the number and type of resources at one’s disposal. Nonetheless, color has a clear and profound impact on visual storytelling, and the last podcast will highlight some of those features.

INSTRUCTIONS: After watching the podcast, choose and apply any desired coloring to your visual narrative.

Writing With Pictures: Step 9 – Conclusion

Conclusion:

Hopefully by taking part in this experiment with transmediation, you have come to a greater appreciation of the medium of comics and the craft of designing them. If you are anything like my students, you also have come to learn some profound insights about the process of composition in general, and will carry over some of these lessons into all future forms of writing. If you are interested in further exploring the wide world of sequential art narratives, I highly recommend reading Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics – an instructional manual written, ingeniously, in the graphic novel format. And in the meantime, please give your students the gift of a diverse approach to literacy and composition in your classroom, one that will serve them well in the 21st century. Excelsior!

Writing With Pictures: Work Cited + Recommended Resources

Major Works Cited:

Busiek, Kurt and Alex Ross. Marvels. New York: Marvel Comics, 1994.

Eisner, Will. Comics and Sequential Art. New York: W. W. Nortan & Company, 1985.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperPerrenial, 1994.

Moore, Alan and Dave Gibbons. Watchmen. New York: DC Comics, 1986.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus: A Survivors Tale. New York: Pantheon, 1993.

Tan, Shaun. The Arrival. New York: Levine, 2007.

Recommended Reading:

Bitz, Michael (2004). “The Comic Book Project: Forging Alternative Pathways to Literacy.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 47 (7), 574-588.

Bitz, Michael (2009). Manga High: Literacy, Identity, and Coming of Age in an Urban High School. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Bitz, Michael (2010). When Commas Meet Kryptonite: Lessons from the Comic Book Project. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Carter, James Bucky (Ed.) (2007). Building Literacy Connections with Graphic Novels: Page by Page, Panel by Panel. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Carter, James Bucky (2009). “Going Graphic: Understanding What Graphic Novels Are – And Aren’t – Can Help Teachers Make the Best Use of This Literary Form.” Education Leadership, 66 (6), 68-73.

Carter, James Bucky (Ed.) (2010). Rationales for Graphic Novels. Gainesville, FL: Maupin House Publishing.

Carter, James Bucky & Evensen, Erick (2010). Super-Powered Word Study: Teaching Words and Word Parts Through Comics. Gainesville, FL: Maupin House Publishing

Cary, Stephen (2004). Going Graphic: Comics at Work in the Multilingual Classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Frey, Nancy & Fisher, Douglas (Ed.) (2008). Teaching Visual Literacy: Using Comic Books, Graphic Novels, Anime, Cartoons, and More to Develop Comprehension and Thinking Skills. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Jacobs, Dale (2007). “More than Words: Comics as a Means of Teaching Multiple Literacies.” English Journal, 96 (3), 19-25.

Monnin, Katie (2009). Teaching Graphic Novels: Practical Strategies for the ELA Classroom. Gainesville, FL: Maupin House Publishing. Weiner, Stephen (2004). “Show, Don’t Tell: Graphic Novels in the Classroom.” English Journal, 94 (2), 114-117.

Schwarz, Gretchen (2006). “Expanding Literacies Through Graphic Novels.” English Journal, 95 (6), 58-63.

Tabachnick, Stephen (2009). Teaching the Graphic Novel (Options for Teaching). New York, NY: Modern Language Association of America.

Weiner, Stephen (2004). “Show, Don’t Tell: Graphic Novels in the Classroom.” English Journal, 94 (2), 114-117.